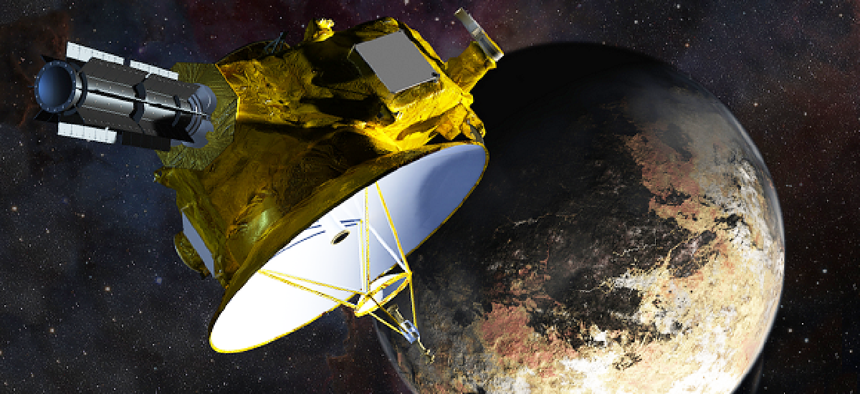

New Horizons: 14 years, 3 billion miles and 2 kbps data downloads

Connecting state and local government leaders

The success of NASA's New Horizons mission was due, in large part, to the meticulous planning -- not just for obvious elements such as navigation and telemetry, but for everything from staffing structure to basic hardware upgrades.

Sprints are in vogue for public-sector IT. Yet when the technology must travel 3 billion miles and arrive at Pluto within a tiny window of opportunity, iterative development and rapid delivery don’t always apply.

Such were the challenges faced by the New Horizons mission team, which this summer celebrated a successful flyby of the dwarf planet that was 14 years in the making. (Although the New Horizons launch took place in January 2006, mission preparation began in earnest in 2001.) And that success was due, in large part, to the meticulous planning — not just for obvious elements such as navigation and telemetry, but for every everything from staffing structure to basic hardware upgrades.

For the spacecraft itself, of course, the technology was locked in at launch. Entire ground systems, however, needed to be upgraded — without losing any compatibility or introducing new software glitches.

“From the beginning, before we even launched, we prepared a longevity plan...where we would actually purchase all new hardware,” Gabrielle Griffith, New Horizons senior ground systems engineer, told GCN. “We knew [the original equipment] would be obsolete by 2015.... We had to make a lot of code changes to get our custom software stack to work on the new computers.”

Those changes required rigorous testing as New Horizons hurtled through space — a discipline that extended to every corner of the mission’s technology. Emulators, backup systems, dry runs and multiple eyes on every line of code have been standard operating procedure.

“The test phase is more emphasized in the space world” because there is so little room for a do-over, said Chris Hersman, a New Horizons mission systems engineer.

All that planning and years-out preparation couldn’t translate into rigidity, however. When New Horizons reached Pluto just 72 seconds ahead of the arrival time scheduled a decade earlier, for example, it was the result of countless adjustments, not some perfectly precise launch trajectory. Hersman compared it to the zoom-and-adjust process one would use on Google maps to get from a nationwide view down to a particular street corner — done over the course of 3 billion miles.

And the IT team faced problems that would be familiar to any government agency: Off-the-shelf components were used (on the ground) wherever possible to stretch tight mission budgets. Old machines were kept around for spare parts because some systems had to remain on circa-2000 hardware. The archive server filled up faster than anticipated and was running out of disk space just as the spacecraft neared Pluto, requiring quick adjustments on the fly.

As the rendezvous neared, the number of personnel involved ballooned from a few dozen to several hundred — and all of them drew on an IT team whose members could be counted on two hands.

According to Julie Napp, a Unix systems administrator at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, it all boils down to a balance of discipline and creativity. Plan carefully, test relentlessly and “when you figure out that something isn’t working, then you make tweaks to fix it.”

Now, with New Horizons well beyond Pluto, the team’s attention is on getting all that flyby data back to Earth — a process that will take 15 months or more, given transmission speeds of just 2 kilobits/sec — and planning for the craft’s next big encounter, with the Kuiper belt in 2019. Another hardware refresh is also in the plans, Hersman said, and the mission could extend as far as 2030.

Luckily, he added, “we’ve got sharp people who are keeping an eye on things and tweaking the knobs.”

NEXT STORY: Building the infrastructure for big data