NIST tests law-enforcement's phone-hacking tools

Connecting state and local government leaders

Researchers with the National Institute of Standards and Technology have evaluated the methods investigators use to access data on damaged or locked phones.

Two methods criminal investigators use to extract data from damaged smartphones have both proved effective, researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Software Quality Group say.

Over the course of a year, they tested two techniques -- JTAG and chip-off -- for accessing data on 10 Android-based smartphones and put then data through eight forensics software programs to interpret the data and determine whether the mobile forensics tools did a better job with the data than traditional methods.

In the end, both methods extracted the mobile data without altering it. “The one thing that we did find are the mobile tools did a much better job of categorizing the data that was contained on the device … into text messages, contacts, call logs, social media-related data, third-party apps, calendar and things like that,” said Rick Ayers, project lead. “[With] a traditional forensics tool, you had to really dig down a little big deeper. It presents you with more of a file system view, like if you were to open up Finder or Explorer in [Microsoft] Windows.”

The research, which is in the quality assurance phase, was funded by NIST and the Department of Homeland Security’s Cyber Forensics Project.

To perform the testing, the team first identified which phones to purchase and test, noting that the two techniques work only on Android phones. Next, they populated the phones with data the way most users would, adding contacts, writing memos, sending and receiving SMS and MMS messages, using video and images, making and receiving phone calls, and collecting geotagged data related to photos and videos along with social media-related data. The team also created two users who would have conversations via direct messages and post status updates.

“We need to know what’s on each phone – that being active data and delayed data,” Ayers said. “That way … we were able to understand and measure how well the tools were able to report the data that is extracted.”

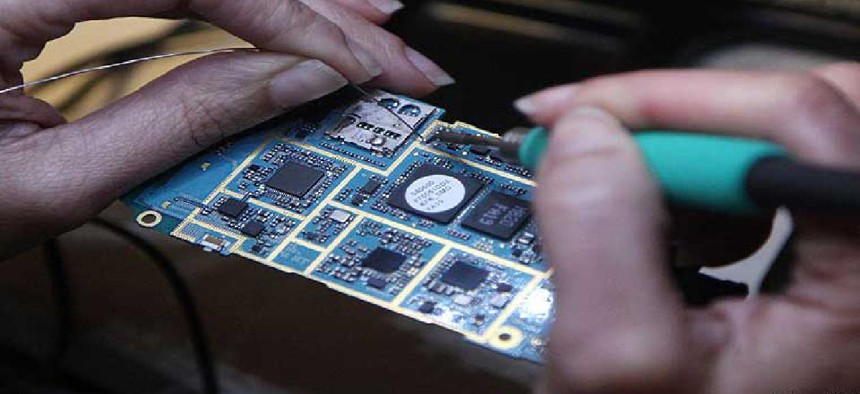

The JTAG method is named after the Joint Test Action Group, which is the association that codified the procedure. Although not developed for forensics, JTAG allows an investigator to extract data by soldering wire to small metal taps that provide access to data on memory chips. Manufacturers use the taps to test circuit boards, but by fusing wires to them, forensics teams can also access data.

“You have to disassemble the device and then access the motherboard,” called a printed circuit board, or PCB, in the phone, said Jenise Reyes-Rodriguez, a NIST computer scientist who handled the JTAG extractions. “Once you identify the path -- which are the contacts you’re going to use to make a connection to the memory on the phone -- then you have to solder some wires to the board. We did that manually here in the lab.”

Next, the team connected the phone with a ribbon cable to a JTAG probe. Then they ran software and extracted the data from the phone, she said.

Whereas the JTAG method requires disassembling the phone, with the chip-off method, investigators grind down the phone’s substrate, or the packaging for the chip, to get direct access to the prongs that hold the chip. “You read the data off the chip that way,” said Barbara Guttman, leader of NIST’s Software Quality Group.

The Fort Worth, Texas, Police Department Digital Forensics Lab and VTO Labs, a private company in Colorado, performed the chip-off extractions.

“We wanted to see if there were any differences by performing a JTAG data extraction vs. a chip-off data extraction, and from our findings across all of the devices, being JTAG and chip-off, they’re consistent,” Ayers said.

Law enforcement officials can benefit from these results in several ways. For instance, they can make informed choices about what tools to use and thereby reduce challenges to admissibility in court because any doubt about the way data was obtained can affect a case.

“Every tool is not perfect all the time, so you [should] know what the better tool for the job is or what the best tool you can afford is,” Guttman said. “Most law enforcement shops with a forensics operation will have purchased at least some tools and then invested in people to be trained to use the tools.”

NIST’s Software Quality Group also packages test protocols in what it calls federated testing tools, a software suite that lets others do NIST-level testing. Developed a few years ago as part of NIST’s Computer Forensics Tool Testing Program to help investigators copy data from seized electronic devices, the idea is that authorities can run tests in advance on their digital forensic software to ensure that it will not fail when a suspect’s device arrives at the lab, according to a 2017 news release.