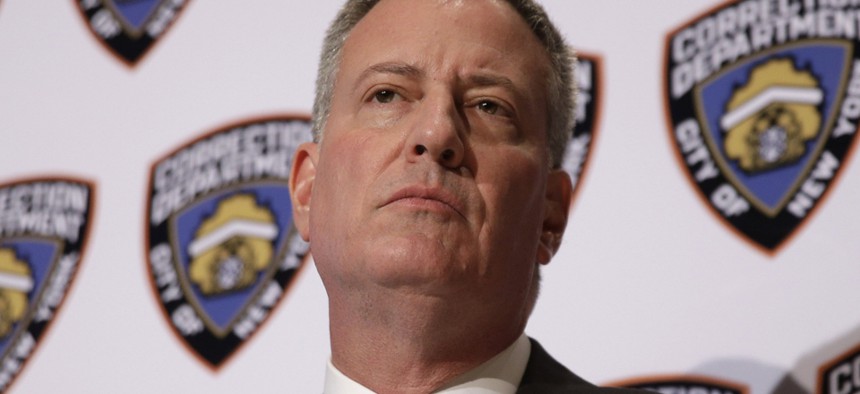

The Cops vs. the Mayor: Bill de Blasio's Big Headache

Seth Wenig/AP

Connecting state and local government leaders

Can the liberal NYC mayor mend fences with increasingly hostile police leadership just as he needs the force to handle protests against bad policing?

Things have been tense between Bill de Blasio and the union that represents the city’s police officers almost since the minute the mayor took office a year ago. He was elected, after all, on a platform of ending stop-and-frisk policing in order to improve community relations with the men and women in blue—an agenda that explicitly rebuked the NYPD’s status quo.

Since de Blasio was sworn in, things have only gotten more uncomfortable. A few days ago, the situation reached an ugly new low when the union called for its members to sign a pledge asking that the mayor not attend their funerals should they be killed in the line of duty.

“Don’t Insult My Sacrifice,” read the document posted on the website of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association. The pledge read thus:

I, _____________________, as a New York City police officer, request that Mayor Bill de Blasio and City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito refrain from attending my funeral services in the event that I am killed in the line of duty. Due to Mayor de Blasio and Speaker Mark-Viverito's consistent refusal to show police officers the support and respect they deserve, I believe that their attendance at the funeral of a fallen New York City police officer is an insult to that officer's memory and sacrifice.

Just a few days after the pledge was posted, Capital New York reported on a seven-minute recording of PBA president Pat Lynch speaking at a delegate meeting in Queens, in which the union leader voiced his anger and frustration at the mayor and his response to the Eric Garner case. Lynch suggested that in response to increased scrutiny of police actions, cops are going to start doing things by the book—and in his remarks, it doesn’t sound like he thinks that’s a good thing.

“We’re going to take that book, their rules, and we’re going to protect ourselves because they won’t,” Lynch said in the recording. “We will do it the way they want us to do it. We will do it with their stupid rules, even the ones that don’t work.”

Among other remarks PBA chief Lynch made about de Blasio on the tape was this: “He is not running the city of New York. He thinks he’s running a fucking revolution.”

De Blasio’s unexpectedly decisive victory in last fall’s election caught many in the New York power structure by surprise. He ran on an explicitly progressive platform that acknowledged the corrosive effect stop-and-frisk policing had on the relationship between New Yorkers—especially young men of color—and the cops charged with protecting the city’s streets. When de Blasio was elected, some critics warned that his tenure would be marked by a descent into lawlessness, to the point where it became a running joke (#deblasiosnewyork). That hasn’t happened.

Critics from the other side of the ideological spectrum, meanwhile, condemned the mayor’s selection of Bill Bratton, a past proponent of stop-and-frisk, as police commissioner. Many said that the appointment of Bratton, an advocate of “broken windows”-style policing, would mean the continuation of inequitable, heavy-handed enforcement of the law. That position of Bratton’s detractors hardened in the wake of Eric Garner’s death during an arrest on Staten Island for the “quality of life” offense of selling loose cigarettes.

As questions about the way police patrol urban streets dominate headlines around the country, de Blasio is finding himself in a bind. He must find a way of dealing with the escalating hostile rhetoric from leaders of the NYPD, even as rank-and-file officers head out to the streets nearly every day to handle mostly peaceful protests of police conduct.

De Blasio is currently pushing hard to bring the 2016 Democratic National Convention to Brooklyn, in part by using the city’s safety as a selling point. Winning the convention would boost his image as a national player who is revitalizing the progressive wing of the party. But back in August, another NYPD union leader, Edward Mullins, opposed the bid by saying "the great city ... is lurching backwards to the bad old days of high crime, danger-infested public spaces, and families that walk our streets worried for their safety." He said the mayor was giving “a public platform to the loudest of the city's anti-safety agitators.” He was presumably referring to the Rev. Al Sharpton, who has been present at many high-profile discussions of race and policing during the de Blasio administration. Last month, in another episode that exposed the rift between the mayor and the cops, a top de Blasio aide with close ties to Sharpton resigned after repeated revelations about her personal life, including her boyfriend’s criminal past and anti-police postings on social media.

With municipal police tactics under an intensifying national spotlight ever since Michael Brown was killed by a cop in Ferguson, Missouri, de Blasio is in anincreasingly delicate position. The mayor met today with representatives of Justice League NYC, one of the main groups behind the days and nights of protests that have followed a Staten Island grand jury’s decision not to indict NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo in the Garner case. Meawhile, city council speaker Mark-Viverito, De Blasio’s close ally and fellow target of the PBA funeral boycott, is heading out to visit police precincts in a move that she says is “all about building bridges.”

Progressive urban leaders around the country, facing their own questions about policing tactics, will surely be watching to see how the nation’s most prominent liberal mayor handles this very uncomfortable situation.

NEXT STORY: Uber Agrees to Stand Down in Portland