Record-Breaking Megadrought Looms for United States

Eddie J. Rodriquez / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

In just a few decades, a huge swath of the U.S. could experience the biggest megadrought that the nation has seen in 1,000 years.

In just a few decades, a huge swath of the US could experience the biggest megadrought that the US has seen in 1,000 years.

New research published on Feb. 12 in the journal Science Advances predicts that this hypothetical could become reality from the Mississippi River to California. It could make the Dust Bowl of the 1930s seem mild by comparison.

No one knows what megadroughts, which can last from 30-50 years, look like. So researchers from NASA and Columbia and Cornell Universities went back 1,000 years to peer confidently into our drier future.

“If you want to study drought variability in the past, trees are the records to do it with,” lead author Benjamin I. Cook, a climate scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, told Quartz. Cook used a network of 835 tree ring chronologies collected throughout much of North America. “The drought signal in these trees is huge,” he said. The record provided a robust, unbroken dryness gauge back to 1000 AD.

Cook’s team was particularly interested in what’s called the “Medieval Warm Period,” which spanned from the 9th to the 13th century. Like most climate change stories, it created winners and losers depending on where you lived. It thawed the north, allowing Leif Erikson and his fellow vikings to colonize Newfoundland in Canada. In the west, it meant drought that “far exceeded the severity, duration, and extent of subsequent droughts,” which may have lead to the collapse of the Pueblo Indian civilization.

This was all before humanity started power-blasting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Cook told Quartz that the Medieval warming provided a natural baseline, allowing him to model human-instigated megadroughts in the future.

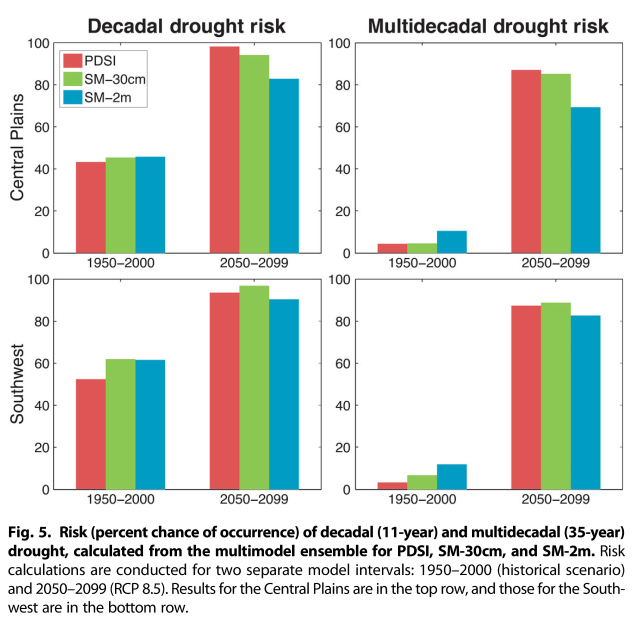

To do this, his team used a popular drought index to connect tree records with 17 different climate models (to be sure). They used historical measurements taken every year since 1850 to confirm the models could match reality (to be extra sure). They also used the models to create two different estimates of soil moisture (to be extra extra sure). One estimate tracks the topsoil and the other measures moisture a few feet deep.

They then hitched the three drought trackers to two greenhouse gas emissions scenarios: one that assumes we do nothing, and the other imagines that we curtail emissions like our lives depended on it. From these pieces, they could generate megadrought predictions for the last half of the 21st century.

The possible future that emerged was sobering.

“Our results show it’s very likely, if we continue on our current trajectory of greenhouse gas emission and warming, that regions in the west will be drier at the end of the 21st century than the driest centuries during the Medieval era,” Cook told Quartz.

But just how likely is very likely? The study puts the chances of a megadrought in the central plains and southwest sometime between 2050-2099 at above 80%. That’s compared with just a 5-10% risk from 1950-2000. Even the milder emissions scenario predicts drying comparable to a Medieval-style megadrought in many locations. “This really represents a fundamental shift in the climate in western North America forced by these greenhouse gases—it’s a shift towards a much drier baseline than anything that anyone alive today has experienced,” said Cook.

“I believe that the results are quite robust,” said James Famiglietti, senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and professor at the University of California at Irvine, who was not involved in the research. “My real concerns are for the implications of the results, which are staggering,” he told Quartz by email.

When asked how a megadrought, if it started today, would affect in the West, Famiglietti said that public water, aquifers, agriculture, rangelands, wildlife and forests would all be at risk. He added: “In California, we’re already in deep trouble. Imagine what the water situation will look like in 2075? Depleted groundwater, decimated agriculture, irreparable damage to ecological habitat. Think apocalypse.”

He’s recently written about the water crisis in California, where he imagined the state as a “disaster movie waiting to happen.” After reading the new study, he told Quartz that it “presents a real doomsday scenario and a situation that is far worse than anything that I had been thinking about.”

But the hazards of a megadrought go even deeper than the water we use for drinking and growing food. Without water, there would be no power to farm or transport drinking water or light our houses or fuel our cars. Water, climate change and energy are absolutely intertwined, according to Vincent Tidwell, a researcher at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico. And he told Quartz that there’s really no part of the energy system that is immune to drought.

Its effects on hydropower are pretty obvious, but water is also heavily used from the drilling well all the way to the power plant. Past droughts have slowed oil and gas recovery and kept oil and coal from being barged up and down Mississippi River. Sometimes drought can even keep new power plants from being built.

Many power companies, especially those burned by drought in the past, have worked out deals in advance to secure water when supplies are tight, said Tidwell. But none of those companies have operated through a megadrought that lasts for decades. And there’s no plan for that. “If things get really, really tight, who knows what might happen,” he said.

But many of the energy providers that he works with, such as the Western Energy Coordinating Council, are starting to plan for the worst. Tidwell even sees good coming out of the looming specter of a megadrought.

“We need to be thinking about intensifying drought and bringing it into our planning, but I think there are also a lot of opportunities, but it’s going to take more cooperation and more coordination to face the uncertainty of the future,” he told Quartz. “We can’t continue the status quo.”