Plummeting Oil Prices Create Problems for Severance-Tax States

huyangshu / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

The big question: How severe will the impact be for state budgets?

This article was originally posted on Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Lower gasoline prices are a great relief for motorists across the country. But for Alaska and a half-dozen other mineral-rich states, the falling price of oil is creating huge budget problems.

Alaska, Louisiana, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Texas, West Virginia and Wyoming top the list of states dependent on severance taxes levied on oil and gas producers. The sharp reduction in oil prices— they fell from $96 a barrel in July to about $50 a barrel this month—has forced those states to consider raiding their rainy day funds, cutting spending or raising taxes to offset shortfalls. Most of the states are eyeing all three.

“All of the severance states are watching this very closely,” said Brian Sigritz, director of state fiscal studies for the National Association of State Budget Officers. “It’s a question of how severe the impact is. States like Alaska, Texas and North Dakota all have built up sizable reserves—rainy day funds. The question is whether they want to turn to those or not.”

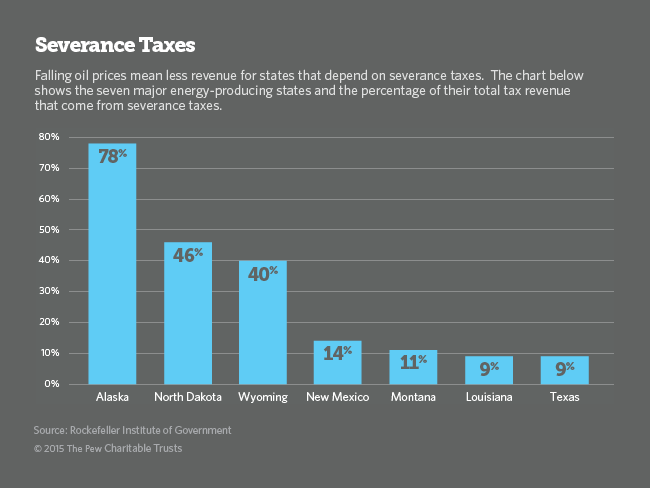

While Texas produces more oil than any other state (more than 104 million barrels a month), only 9 percent of its revenues comes from severance taxes. Alaska, by contrast, produces 16 million barrels a month but gets 78 percent of its revenue from severance taxes, according to the Rockefeller Institute of Government. That is the highest percentage, by far, of any state.

“The good news for the states with the high reliance on severance taxes is that they had not been hit as hard as other states during the Great Recession,” said Lucy Dadayan, senior policy analyst at the Rockefeller Institute. “The bad news is that now they need to address the fiscal challenges created by the volatility in severance taxes.”

The plummeting oil prices generated this exchange between Alaska state Sen. Mike Dunleavy, a Republican, and Legislative Finance Division Director David Teal at an Alaska Senate Finance Committee hearing on the budget last month. The dialogue was reported by the News-Miner newspaper:

“In your opinion, is it wise for this body to continue to budget on $105 barrels of oil?” Dunleavy asked.

“No,” Teal answered.

“In your opinion, is it wise for this body to budget on $90 barrels of oil?” Dunleavy continued.

“No, it isn’t,” Teal said.

“Eighty-dollar barrels of oil?”

“No, it isn’t,” Teal said.

“Sixty-dollar barrels of oil?”

“You’re getting close,” Teal said.

Teal told Stateline that the revenue loss is compounded by tax credits. “The short story is that our severance tax is negative,” Teal said.

Large oil producers can take oil exploration and development tax credits from the state against their taxes, and those credits have increased. In addition, companies can sell unused tax credits to other companies. The state buys these “purchasable” credits, and net revenue declines further.

For fiscal 2015, total production tax credits amount to $1.4 billion, Teal said. Gross revenue from oil and gas production taxes in fiscal 2015 is expected to be about $1.3 billion. For fiscal 2016, credits are expected to exceed production tax revenue by nearly $400 million, Teal said.

The bottom line: Alaska has a $3.6 billion hole in its $6.1 billion budget. Independent Gov. Bill Walker is calling for 5 percent to 8 percent spending cuts to help close the gap.

Teal noted, however, that Alaska has healthy reserve balances. Right now, the state’s budget deficit is 163 percent of the state’s revenue. The reserve funds, he said, total about $16 billion, which would buy the state about three years, if revenue fell to zero.

Alaska also could turn to its Permanent Fund, a pool of surplus state revenues from the development of the state’s oil and gas reserves that is invested and pays an annual dividend to all Alaska residents who meet eligibility requirements. That fund has a balance of about $50 billion, Teal said, but tapping it to support government spending would be politically perilous.

“We will reduce spending, but we will still end up with a deficit of $3 billion (next fiscal year),” Teal said. He anticipates the low oil prices to last no more than a couple of years.

Dunleavy, the state senator, said the budget can be cut in many ways before it would become necessary to draw down rainy day funds. But unless the state makes the “hard decisions” with major spending cuts, he said, it will “never get to what are essential services and what are not.” He believes the state will not raise taxes or tap the rainy day fund this year.

“I think this is going to be a year of cutting. Substantial cuts like the state has never seen before,” he said. “It would be a failure if we didn’t cut.” He noted, however, that the budget drafting has just begun and anticipates some hard-fought battles in the legislature.

Reserve Fund Reckoning

According to a report from The Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew funds Stateline), three of the top five states with the greatest revenue volatility are Alaska, North Dakota and Wyoming, which are highly dependent on severance taxes. “From fiscal year 1995 to 2013, corporate income tax and severance tax on oil and minerals consistently were more volatile than other major state taxes, such as those on personal income and sales of goods and services,” the report said. Alaska has the greatest year-to-year revenue volatility rating of all states.

While rainy day funds can offer temporary relief, Rockefeller’s Dadayan suggests that “in the long run, a more viable option would be having a more balanced tax structure in place.”

Louisiana, another state with severe severance tax declines, has statutory restrictions that limit withdrawals from its rainy day fund. According to Greg Albrecht, chief economist for the Louisiana Legislature, for every dollar drop in the price of a barrel of oil, the state loses $11 million. Albrecht estimated that the severance taxes will drop $80.4 million in the current fiscal year and $222.7 million in the next fiscal year if prices stay where they are now.

Albrecht said the state faces a $1.6 billion shortfall for next fiscal year, including other decreases in tax collections. “We’re exacerbating the problem with oil and gas price weakness,” he said. He added that because state legislative elections will be held next fall, it may be politically difficult to cut the budget or raise taxes to fill the deficit hole. “This is going to be really challenging.”

Boom Cushions North Dakota

While North Dakota is experiencing the same kind of severance tax downturn as the other states, the size of the boom there has offset the impact, according to North Dakota House Majority Leader Al Carlson. “By no means are we broke,” the Republican said. “But instead of $8 billion in revenue from oil, we’re anticipating $4 billion.”

Many states would panic at those numbers, but not North Dakota, he said. The state’s reserve fund is at about $1 billion, although it can’t be touched by law until the state imposes a 2.5 percent cut to all state agencies, he said. During the height of the boom, the state set aside money for water projects, disaster relief and infrastructure improvements, especially in the western part of the state which includes the oil fields.

“The sky is not falling in North Dakota,” he said.

Yet, despite the sunny outlook, North Dakota still ranks high at third in revenue volatility, according to the Pew index, and even Carlson admitted that he and other lawmakers are counting on oil prices rising again by the end of 2015.

“The oil companies are not leaving,” he said. “They may slow down but they are not leaving because we have a real honey hole for oil.”

In Wyoming, the state’s revenue estimating group last month revised downward anticipated revenue by $217 million, mostly due to the downturn in oil and natural gas prices. The previous forecast in October was based on an $85 a barrel oil price; last month’s price was $39 a barrel. The reduction is on top of a $4 million deficit lawmakers were confronting at the start of this year’s legislative session.

Buck McVeigh, executive director of the Wyoming Taxpayers Association, which tracks state revenues, said the state has a $2 billion rainy day fund and can weather the downturn. “We are pretty well seasoned at preparing ourselves for these types of situations,” he said.

The state has considered broadening its tax base over the years, and possibly developing a corporate or personal income tax, to avoid the volatility. McVeigh said that might make sense from an economist’s standpoint, but the state has always reverted to severance taxes.

“There’s that natural reluctance to (new taxes),” he said. “With minerals ‘you have to dance with the one that brung ya.’”

“From an outsider looking in, you’d have to say this isn’t a good model,” he added. “But if you look at the track record of this state and their fiscal policies, they are pretty darn good at it.”