Philadelphia's Quasi-Secret Effort to Make Chinese Takeout Healthier Is Working

Matt Rourke/AP file photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

Nearly 200 of the city’s Chinese restaurants have reduced the amount of sodium in some of their most popular dishes, and no one seemed to notice.

The good people of Philadelphia are no different from you or me: Sometimes, after a long day at work, all they want is a Styrofoam container of cheap and steaming hot lo mein.

In fact, there are more Chinese restaurants in Philly than there are chain restaurants combined, says Giridhar Mallya, who directs policy and planning at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. But like so many fun habits, this one has consequences—most take-out Chinese dishes are also sodium-bombs.

According to the USDA, a standard order of kung pao chicken contains 2,428 milligrams of tasty, tasty sodium. General Tso’s chicken, another classic, averages 2,325 milligrams per serving. The Centers for Disease Control, meanwhile, recommends that Americans consume less than 2,300 milligrams of sodium per day , and even less for adults over 51 and those with medical conditions. Excess sodium, the agency warns, leads to higher blood pressure and increases the risk of heart disease and stroke, which combined kill more Americans annually than anything else.

Philadelphia is no exception. According to a 2014 study [PDF], over one-third of adults in the city have high blood pressure, a higher share than any of the other top 10 largest cities in the U.S. The African American population is particularly at risk: Nearly 50 percent of black non-Hispanics in Philly have high blood pressure.

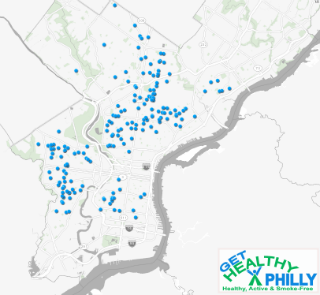

Those statistics made the small, often independently owned Chinese takeout joints that dot the city a particularly appealing target for public health officials, says Mallya. Of the estimated 430 Chinese take-out restaurants in Philadelphia, the majority are in low-income black and Hispanic communities, he says. So in 2012, the city partnered with a number of community organizations, including the Temple University Center for Asian Health , the Asian Community Health Coalition , and critically, the Greater Philadelphia Chinese Restaurant Association, to reduce the salt content of Chinese takeout.

But first, the group had to convince restaurants to participate. Of the 221 Philadelphia Chinese take-out chefs and owners originally surveyed by the organizations, four in five said they believed consuming too much salt was harmful to one's health. But only 58 percent said they believed reducing the amount of salt in their menu options would benefit their restaurants. Fewer than half said customers would choose menu items identified as low-salt. The goal of the Philadelphia project, then, would be to change the foods “without disturbing the flavor,” as researchers wrote in the project’s baseline study —a difficult task given that “salt plays a significant role in taste, processing and preservation of food.”

What became the “ Healthy Chinese Take-Out Initiative ” wouldn't be a secret, exactly. There was a smattering of press coverage . Some of the 206 Chinese restaurants that eventually did sign up proudly displayed a decal on their store windows. But the initiative's success hinged on the restaurants’ abilities to lower their dishes' salt content without customers noticing, complaining or—worst of all—choosing to forego hot plates of noodles altogether.

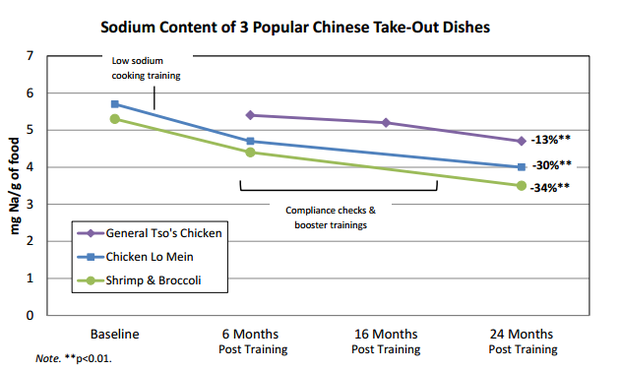

Though 67 percent of initial participating restaurants said “providing low-salt options is easy to do,” two-thirds of them wanted training in purchasing, cooking and marketing low-salt food items. So the project offered Chinese-language cooking classes with a professional chef from the Culinary Institute of America, and Chinese-language meetings with public health researchers. Restaurant operators were advised to try several specific strategies: reduce the amount of salt-laden sauce in their dishes; purchase low-sodium ingredients; use fresh instead of canned produce; use non-salt ingredients like herbs and spices to add flavor; distribute fewer soy sauce packets and use standardized measuring tools while cooking. The first efforts focused on two popular (and delicious) dishes: chicken lo mein and shrimp and broccoli. The initiative aimed to reduce the salt content of those dishes by 10 to 15 percent.

Six months after taking baseline sodium measurements for those two dishes, the project’s researchers introduced another dish to the program, one that the restaurants hadn’t been trained to de-salt: General Tso’s chicken.

So did it work? These are the initiatives’ latest results [PDF], released last month:

Philadelphia Department of Public Health

The initiative more than doubled its original sodium reduction goal in the two initial target dishes, and even the dish that wasn't included in the original intervention had less salt two years after the training. (All three dishes now have sodium content below daily dietary guidelines, though they still exceed guidelines for a single meal.) Mallya says the project’s organizers are particularly cheered by the additional 10 percent drop in sodium content between 2013 and 2014. “We often see initial improvements, but then they drift back to baseline,” he says. “It’s reassuring to see … that continued reduction.”

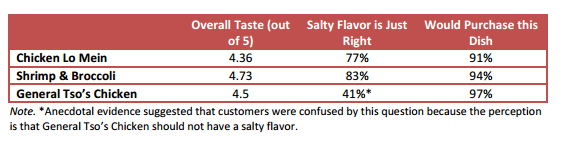

Taste tests, conducted at nine participating restaurants with 324 tasters, found that customers were generally happy with the changes. The vast majority said they would purchase the reduced-salt dishes:

Philadelphia Department of Public Health

Now the initiative can focus on publicity. “One of the best ways to help people reduce salt is to not tell them,” says Mallya. “Now that we were able to achieve some of these reductions, we want the community to know about the changes being made.”

NEXT STORY: A Pregnancy Prevention Breakthrough in Colorado