A Pregnancy Prevention Breakthrough in Colorado

jennyt / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

The state’s teen birthrate dropped 40 percent between 2009 and 2013. Here's how that happened.

This article originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

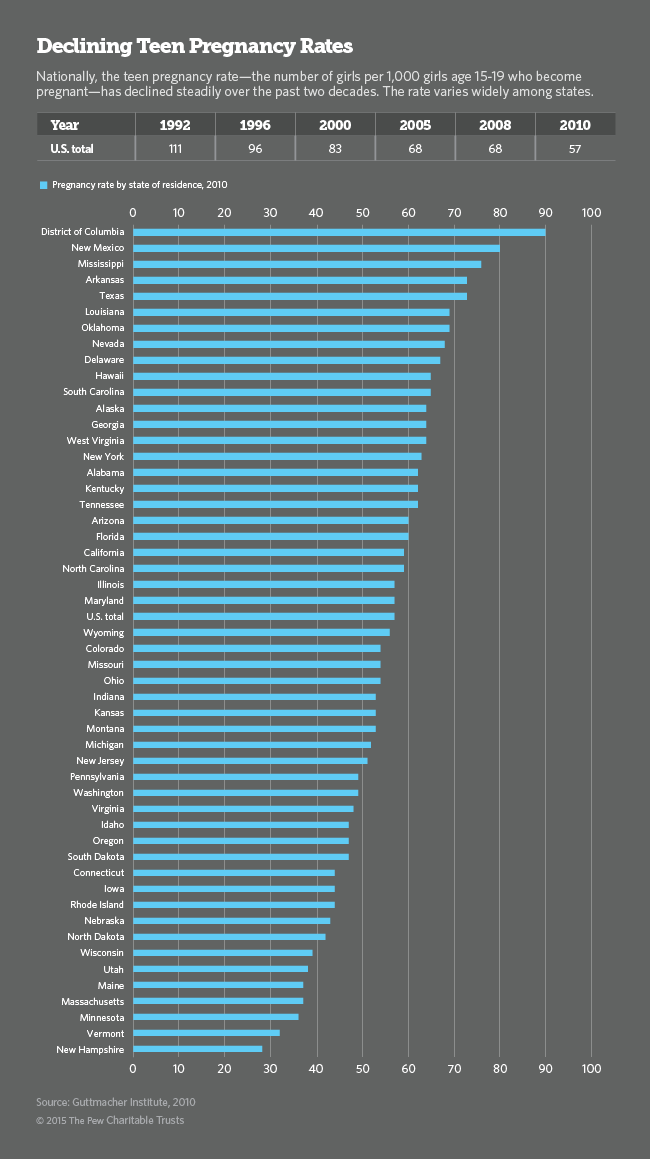

President Barack Obama hailed a landmark achievement in his State of the Union address last month: Teen pregnancies in the U.S. have hit an all-time low. But the U.S. still has a teen birthrate of 31.2 per 1,000 teens, nearly one-and-a-half times the rate in the United Kingdom, which has one of the highest rates in Western Europe.

Colorado may have found a way to close the gap. The state’s teen birthrate dropped 40 percent between 2009 and 2013, driven largely by a public health initiative that gives low-income young women across the state long-acting contraceptives such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and hormonal implants.

Backed by $23.5 million from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, Colorado attracted national recognition for its program after Democratic Gov. John Hickenlooper announced the results of a cost-savings study last summer. The state saved $42.5 million in 2010 alone, an average return of $5.85 in avoided Medicaid costs for prenatal, delivery and first year of infant care for every $1 spent on the program.

More important, Hickenlooper said, the initiative “has helped thousands of young Colorado women continue their education, pursue their professional goals and postpone pregnancy until they are ready to start a family.”

According to program supervisor Greta Klingler, Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Virginia and Wisconsin have asked Colorado to share its techniques and lessons learned. Illinois is already adopting some of Colorado’s methods in a statewide Medicaid program for unwanted pregnancy prevention, she said. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is also seeking more details from Colorado.

Bill Albert, chief program officer at the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, pointed to the promise of state-based programs that rely on low-maintenance, highly effective methods of contraception coupled with good counseling.

“We’ve made progress, but if we’re going to continue making progress, efforts going forward will have to be as innovative and up-to-date as possible,” Albert said.

But Colorado’s program will end this June when its private grant runs out, unless lawmakers approve state funding to keep it going for another year. A $5 million funding bill was introduced this month with bipartisan sponsorship, but it won’t necessarily be an easy win, especially in the Republican-led state Senate.

One GOP lawmaker has already announced his opposition, saying he believes that IUDs destroy embryos, a belief that is not backed up by science. “As a general matter, anytime you bring up the subjects of teens, sex and contraception,” said Albert, “you can expect a vigorous debate.”

Why It Worked

Years of public health research substantiates a simple truth: Young women and their partners are not always prepared to use contraception in the heat of the moment. As a result, condoms are among the least-effective methods of birth control. Even the birth control pill is relatively ineffective, because girls often forget to take it every day or fail to renew their prescription each month.

Other methods, such as a vaginal ring that must be replaced each month, an injection that lasts for 30 days and a hormone patch that is good for three months, all require planning.

Teenage sex is sporadic, said Klingler, and girls don’t necessarily know when they are going to have sex. That’s why devices known as long-acting reversible contraceptives or LARCs have had the best results. Once they’re inserted, they’re maintenance free – no planning required. An IUD can remain inserted for five to 10 years; a time-release hormonal device implanted into a girl’s arm lasts three years.

The hitch is that the devices are expensive – up to $900 for an IUD and $800 for a time-release implant. As a result, low-income women and teens often opt for cheaper solutions such as the pill or condoms. The upfront cost also makes it difficult for physicians to stock the devices, often causing a gap of a week or more between the time a girl orders the device and when she starts using it.

Once a girl has gone through all the hard work of making a decision, Klingler said, that delay can be consequential. “If just a week goes by, she can get pregnant.”

Another barrier to the use of LARCs is lack of awareness. Nationwide, only 10 percent of women of all ages rely on the devices, compared to as many as 32 percent in European countries. In a survey conducted late last year by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, 68 percent of respondents lacked knowledge of IUDs and 77 percent knew little or nothing about hormonal implants.

A Boost from the Affordable Care Act

A provision in the Affordable Care Act requires insurance companies to cover the cost of all contraceptive devices approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Medicaid also must cover FDA-approved birth control. So far, though, insurance companies are not consistently complying with the ACA provision and states aren’t rigorously enforcing it. Until they do, and even after that, physician practices with tight cash flow may not be willing or able to keep an adequate supply of the devices on hand.

Dr. Larry Wolk, Colorado’s chief public health medical officer, said training providers on the importance of giving women a full range of contraceptive choices has been key to the program’s success. Once physicians understand the relative effectiveness of LARCs and learn how to explain the pros and cons to their patients, they’re immediately onboard, he said.

Colorado used its grant money to train health care professionals and supply contraceptive devices in all 65 of the state's Title X family planning clinics, which are state- and federally subsidized health clinics for low-income women. These clinics are located in local public health departments, hospitals, community health centers and nonprofit clinics across the state, some of which are in or near public high schools.

Nationwide, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funds a network of 4,400 clinics serving about 5 million people per year. Federal funding for the clinics, which began in 1970, is currently at $287 million. Over the past five years, Title X funding has decreased by nearly $40 million. This year’s White House budget includes a $14 million increase in funding for the program.

Colorado’s family-planning initiative served 65,000 low-income women last year, about 95 percent of the low-income female population. That’s an increase from 52,000 women served in 2008, before the program began.

During the program’s first four years, the use of LARCs among family-planning clients grew from 4.5 percent to 19.4 percent, and the teen birthrate dropped an unprecedented 40 percent. The number of teens giving birth to second, third and subsequent children also plummeted 53 percent.

Going forward, Wolk said, “We want to extend this beyond the core safety net to all primary care and women’s health centers that are providing these services.” He said this year’s funding request for $5 million will cover expansion of the program to all women’s health providers in the state. After that, the state should need only about $2 million per year, once ACA-required reimbursements from Medicaid and private insurance start picking up the slack.

“We’ve made the first step of showing that unfettered access can really move the needle,” Wolk said. “The goal now is to continue the program so we can sustain the success we have in reducing the numbers of unintended pregnancies. If we’re able to continue, we expect the rate (of teen births) to go down even more.”

Earlier Projects Shut Down

In 2007, Iowa received funding from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation for a project similar to Colorado’s. A five-year demonstration project, the Iowa Initiative to Reduce Unintended Pregnancies, concluded in 2012. While it was running, the number of women using IUDs or implants increased from 2,200 in 2007 to more than 9,700 in 2011. Accidental pregnancy dropped 4 percent, one of the biggest declines in Midwestern states at that time.

Since then, Iowa lawmakers have approved a Medicaid program that makes birth control free to all women with incomes less than 300 percent of the federal poverty level ($35,300 for an individual). The state also requires health insurers to cover all birth control methods in their health plans.

In 2007, The Contraceptive Choice Project, which was funded through the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, analyzed the effectiveness of providing no-cost contraception to nearly 10,000 women of all ages in the St. Louis area.

Of the 1,404 teens in the study, 72 percent chose a LARC method. The teen pregnancy rate among those who participated was 34 per 1,000 teens compared to a national average at the time of 159 per 1,000 teens. The abortion rate among teens in the project also dipped to 10 per 1,000 compared to a national average of 42 per 1,000.

Both Iowa’s and St. Louis’ experimental projects have been shuttered.