Citing Cost to Taxpayers, Cities and States Tackle Obesity

Peter Kotoff / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

Cities and states are tackling obesity, and with good reason: obesity-related health problems cost the nation as much as $210 billion each year.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

More than 35 percent of Arkansas adults are obese, making it the heaviest state in the nation. Gov. Asa Hutchinson looked at those numbers and saw two problems: an increased risk of all sorts of health challenges, and an increased burden on taxpayers.

Armed with data about the devastating effects of obesity, Hutchinson, a Republican, last month launched a 10-year plan to combat the problem in his state, from tightening nutritional standards in schools to creating more walkable communities and improving access to affordable, healthy foods.

“I’m a conservative,” Hutchinson said. “I’m concerned about tax dollars as well as good health. There’s a consequence to the taxpayer because of bad health habits.”

Arkansas isn’t the only state to take on obesity this year. Governors in New York, Georgia and Tennessee have all announced plans to combat high rates of obesity among their citizens.

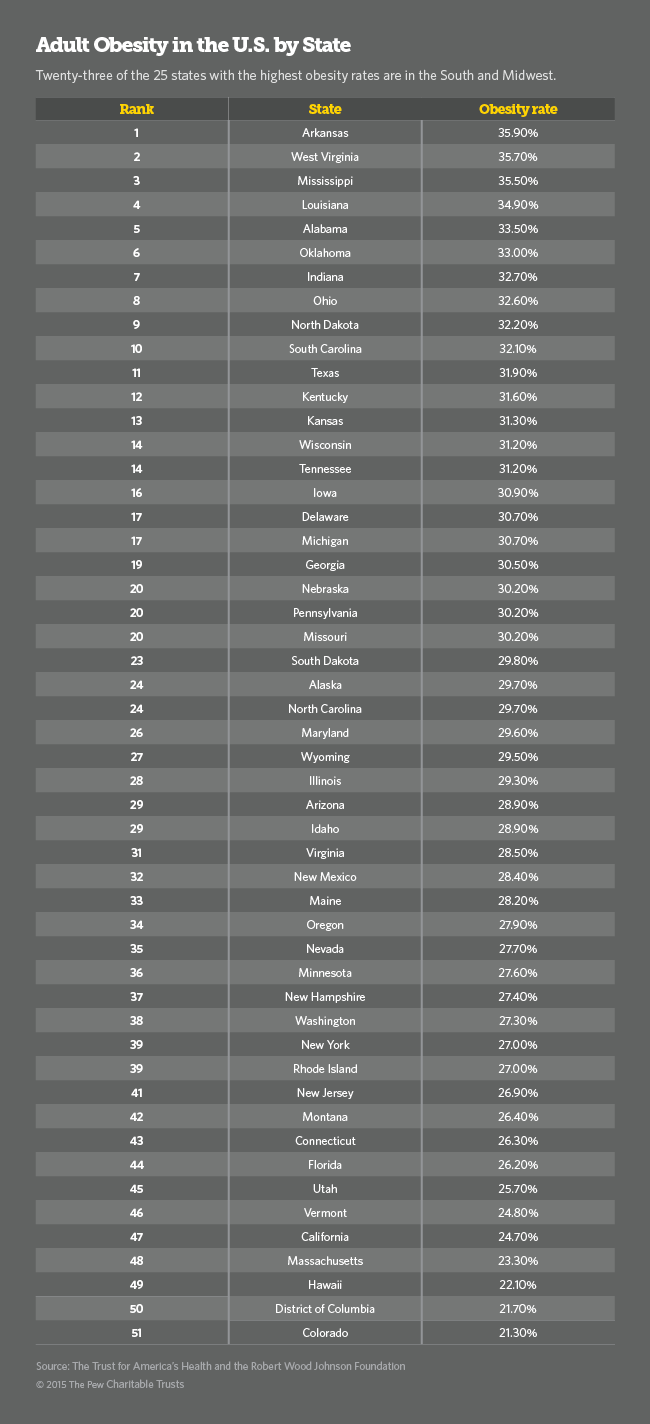

Nationwide, a third of all adults—78 million—are obese, up nearly 50 percent since 1990, according to Health Intelligence, a health data analysis site. The top 10 heaviest states are in the South and the Midwest, according to a new report by the State of Obesity, a project of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Trust for America’s Health, an advocacy and research group based in Washington, D.C.

Cities and states have a vested interest in tackling the issue. Obesity, defined as a body mass index of 30 or higher, is a leading cause of preventable death in the U.S., and can cause a host of chronic health issues, from diabetes to high blood pressure to cancer.

Across the country, obesity-related health problems cost $147 billion to $210 billion each year, according to the State of Obesity. Obesity is also associated with diminished productivity on the job and to work absenteeism costing the country $4.3 billion per year, according to the report.

State and local governments can play a crucial role in reducing obesity rates, said Rich Hamburg, deputy director of the Trust for America’s Health.

“The obesity epidemic is one of the nation’s most serious health crises,” Hamburg said. “There’s no silver bullet here. You need dedicated resources, you need policy changes and you need buy-in. When you get buy-in by local leaders that can only help.”

State Efforts

The highest obesity rates in the U.S. are found in Arkansas (35.9 percent), West Virginia (35.7 percent) and Mississippi (35.5 percent). Colorado (21.3 percent), the District of Columbia (21.7 percent) and Hawaii (22.1 percent) have the lowest rates of obesity.

Race, class, culture and ethnicity play a big role in obesity. American Indians and Native Alaskans have the highest rates of adult obesity, at 54 percent, according to the Trust for America’s Health. Among African-Americans, 47.8 percent are obese, while 42.5 percent of Latinos are obese. Asian-Americans have the lowest rates of obesity at 10.8 percent, while 32.6 percent of whites are obese.

Research suggests that the poorer you are, the more likely you are to be obese. This is particularly true for white and black women, according to the Food Research and Action Center. Among adults, 36.2 percent of high school dropouts (who are much more likely to be poor) are obese, compared to 21.5 percent of college graduates, according to the United Health Foundation.

Why the disparity? One reason is that low-income neighborhoods are often “food deserts,” isolated rural and urban pockets where grocery stores and farmers markets are in scarce supply—but places where fast food restaurants are abundantly available. When healthy food can be found in these neighborhoods, it is more expensive than the filling, starchy fare that is plentiful.

Over the past couple of years, obesity rates have stabilized somewhat, but they remain stubbornly high, health advocates say, with adult obesity rates increasing in Kansas, Minnesota, New Mexico, Ohio and Utah, according to the State of Obesity.

In Georgia, where the obesity rate is 30.5 percent, government agencies initiated a partnership with the Atlanta Falcons and the Atlanta Braves in 2011 to reduce obesity and increase physical activity among schoolchildren. The ongoing program includes an app to assess fitness and uses social media to get its message across.

In March, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam, a Republican, set up an initiative that helps local communities create programs supporting physical activity, healthy eating and tobacco abstinence.

In New York, where 27 percent of adults are obese, Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, in July created a new program to provide $6.7 million in grants to 26 organizations across the state to increase physical activity and access to healthy food for schoolchildren.

Hutchinson, the Arkansas governor, said his plan will tackle obesity on several fronts, including encouraging physical education, creating healthy worksites and more walkable communities and reducing sugar-sweetened drinks.

Some of the programs will cost money, while others will save money, Hutchinson said.

Above all, he said, “The state should resist heavy-handed mandates and should work toward partnership with the private sector and provide incentives for healthy living.”

1 Million Pounds

Like many, Mick Cornett, the mayor of Oklahoma City since 2004, had always struggled with his weight. Ten years ago, a couple of things happened that shook him: First, he happened upon a magazine article declaring that Oklahoma City was the fattest in the country. No mayor wants to read that. Then he went online, plugged his height and weight into a BMI calculator—and was stunned to find that at 220 pounds, he was technically obese.

“I spent a few months trying to reconcile my own issues with obesity,” said Cornett, a Republican. “Then I started really looking at the city and why the culture of our community had a specific problem with obesity.”

He realized that the entire city had been built “for cars, not people”—including the city’s plethora of drive-thru lanes at fast food restaurants. And, as a former city hall reporter, he understood the power of messaging. So rather than scolding the city, at the end of 2007 Cornett invited its residents to lose 1 million pounds with him. Over 50,000 residents have signed up for the citywide diet.

Cornett is hardly the only mayor to tackle obesity. Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, an independent, tried and failed to institute a sales tax on sugary drinks and tried to ban supersized sodas in restaurants. (He was more successful in banning artificial trans fats in 2006.)

Cornett said he decided to work with fast food restaurants, encouraging them to incorporate healthier fare such as salads and grilled food into their menus, and even having competitions for the tastiest healthy meal. Churches and corporations joined in as well. He did it without any taxpayer dollars, he said.

Government has a role to play in shaping citizens’ health, Cornett said, and encouraging his constituents to lose weight was just the first phase. Now, he’s working on long-term projects to make the city a healthier place to live, building sidewalks and jogging paths to make it more pleasant to commute without a car.

A project to eradicate the food deserts in poorer neighborhoods is also underway, with two major supermarkets funded with tax incentives to encourage developers to invest in neighborhoods that have festered for decades.

“There’s still a lot of hurdles to go through,” Cornett said. “It takes a generation to make a cultural shift like this.”

Teresa Wiltz writes for Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

NEXT STORY: Uber vs. Austin: A Battle of Driver Background Checks