States, CDC Seek Limits on Painkiller Prescribing

David Smart / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

The nation’s governors are calling for a halt to liberal prescribing of opioid painkillers.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Christine Vestal.

As medical director for the Washington state workers’ compensation program in 2001, Dr. Gary Franklin made a chilling discovery: Otherwise healthy workers who took painkillers for minor injuries were ending up dead a few years later.

“It was shocking,” Franklin said. “Workers are on the job, they report a back sprain, and then they are dead.” In dozens of cases, patients had been prescribed opioid painkillers for chronic pain. Most had taken drugs like OxyContin consistently for months or years.

Doctors were prescribing high doses of opioid painkillers in most other states too. Doctors and their patients had been assured the pills were safe, and yet thousands of people were dying. “They would take one more pill before going to bed and never wake up,” Franklin said.

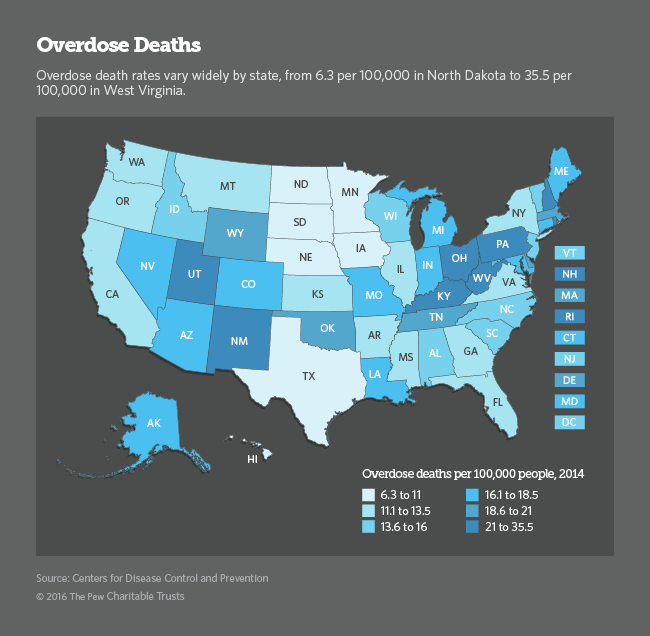

Now, in the throes of the deadliest drug epidemic in U.S. history, governors, presidential candidates and major health care organizations — from insurance companies to physician associations — are calling for limits on the number and strength of opioid pills prescribed. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is close to taking the unprecedented step of issuing national guidelines to curb liberal opioid prescribing practices widely blamed as the cause of the epidemic.

“It isn’t drug dealers that are on our South American border that are our biggest challenge,” Democratic Vermont Gov. Peter Shumlin said last month at a meeting of the National Governors Association. “It is our drug dealers who are FDA-approved selling the stuff in every pharmacy in America.”

Both Democratic and Republican governors unanimously support the CDC initiative and have pledged to promote the voluntary physician guidelines in their states. But the American Medical Association and pain organizations backed by drugmakers are complaining the initiative could make it difficult for chronic pain sufferers to get the pills they need.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved OxyContin and other opioid pain medications in the mid-1990s for short-term pain only. But physicians quickly started prescribing the effective new pills for long-term or chronic pain. When patients built up a tolerance and the pills stopped working, pain experts and drug company representatives instructed doctors to give higher doses. They assured doctors the pills were safe and nonaddictive.

In fact, Washington and more than 20 other states made clear that doctors couldn’t be disciplined for prescribing high doses of opioids by enacting so-called intractable pain acts.

Franklin and five other researchers were the first in the U.S. to publish a study showing that the relatively new opioid pain medications were killing people. Since then, the CDC has reported more than 200,000 overdose deaths from the pills.

But in the decade since Franklin and others began reporting those grim statistics, only Washington and a few other states have attempted to educate doctors about the overdose and addiction risks of powerful pain relievers such as OxyContin, Percocet and Vicodin.

The CDC’s initiative could change that.

Pain Relief and Safety

The CDC’s draft proposal urges primary care doctors to try drug-free methods to relieve chronic pain, such as exercise, weight loss and physical therapy, as well as non-opioid pain relievers such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen, before resorting to powerful opioid pills. If opioids are needed, the guidelines recommend starting with the smallest effective dose of immediate-release opioids, avoiding more dangerous time-release formulations except when needed.

The AMA has generally supported the concept of more cautious opioid prescribing. But the group has criticized the CDC proposal for lacking “a patient-centered view and any real acknowledgement of the problems chronic pain patients may face.” More than a thousand individual patients have urged the CDC in online comments not to pressure doctors into withholding the opioid painkillers they rely on.

Purdue declined to comment on the proposed guidelines and, like other drug companies, it did not file public comments with the CDC. But the Washington Legal Foundation, a pro-business nonprofit that often represents pharmaceutical companies, wrote a letter to the CDC expressing “extreme concern” over what it said were flawed procedures used in developing the guidelines.

Representatives from the U.S. Pain Foundation and the American Academy of Pain Management, which receive financial support from pharmaceutical companies, have also argued that the federal agency relied too heavily on the advice of addiction experts and not enough on advocates for pain patients.

Since those complaints, the agency has added 130 studies, undergone three independent peer reviews and consulted additional experts, including representatives from the groups that have been critical, according to Dr. Debra Houry, an emergency room physician on the CDC’s opioid guidelines team. As a result, the CDC guidelines, originally slated for release in January, were delayed.

For acute pain resulting from non-traumatic injuries or minor surgery, the CDC’s draft proposal suggests sending patients home with only three days’ worth of pain pills instead of a 30-day supply, which is common practice in most U.S. hospitals and physicians’ offices.

Doctors who prescribe the extra pills tell patients they are “just in case” the pain lasts longer than the expected day or two. But advocates for safer prescribing say the extras are often given to friends or taken from medicine cabinets for recreational use, further fueling the drug epidemic.

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, proposed the same three-day limit last October and Shumlin adopted a similar measure in Vermont last month. At the governors meeting, Shumlin urged all governors to use their authority under medical licensing laws and as major health care purchasers. He called on them to limit the number of opioid pills doctors may prescribe to patients taking them for the first time following a non-traumatic injury, minor surgery or dental procedure.

One of the most controversial recommendations in the CDC’s draft proposal calls on family doctors not to prescribe opioid doses higher than the equivalent of 50 milligrams of morphine per day without consulting a pain specialist.

In 2007, Washington state set the threshold much higher: no more than the equivalent of 120 milligrams of morphine per day.

Even at that level, drugmakers were aggrieved. “We got sued immediately,” Franklin said. He also received a letter from Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, calling the dose limit “too stringent” and arguing it could “interfere with access to appropriate and effective pain care for persons suffering from chronic pain.”

Coincidentally, within days of sending the letter, Purdue executives pled guilty to misleading doctors and patients about OxyContin’s risk of addiction.

The federal lawsuit against Washington’s opioid dose limit was dropped in 2010 and doctors across the state generally adhered to the recommendations, Franklin said. Opioid overdose deaths in the state dropped from a high of more than 500 in 2009 to about 300 in 2014. The number of prescriptions also declined by nearly a third, as did the number of workdays lost to injury.

Opioids and Heroin

Starting in the late ’90s, pharmaceutical companies began telling physicians that opioid pain relievers were safe, effective and nonaddictive. As momentum for greater use of the powerful drugs grew, an organization that accredits medical professionals, the Joint Commission, declared pain the “fifth vital sign,” requiring doctors and other medical professionals to measure and treat pain as they would any other vital sign — temperature, blood pressure, pulse, breathing rate.

Although the FDA had recently approved OxyContin and other opioids for severe acute pain only, doctors and hospitals — which are rated on their effectiveness at eliminating pain — began using opioids as a first line of treatment for nearly every kind of acute and chronic pain, from toothaches and migraines to sports injuries, back pain and cancer.

Sales of prescription painkillers spiked immediately. By 2012, health professionals were writing more than 250 million prescriptions for painkillers per year, according to the CDC — almost enough for every American to have a bottle of pills. Vicodin or its generic, hydrocodone with acetaminophen, became the most prescribed medication in the country.

In 2014, nearly 2 million people had a prescription painkiller addiction and more than half a million were addicted to heroin, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Following a wave of opioid painkiller overdose deaths starting in 2001, heroin overdose deaths began piling up. The CDC has reported that people who take opioid painkillers are 40 times more likely to use heroin. Another study found that three in four heroin users were introduced to opioids through prescription drugs.

Many experts have speculated that the recent rise in heroin use results, in part, from a federal and state crackdown on doctor’s offices where bogus prescriptions are written in exchange for cash payments. The decline in “pill mills” cut back the supply of illicit painkillers and made them more expensive, prompting many to switch to cheaper heroin, the theory goes. A new study in the New England Journal of Medicine concludes there is insufficient evidence to support that theory.

The Next Generation

Pain experts, including the head of the national organization Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, Dr. Jane Ballantyne, emphasize that prescription pain relievers are killing thousands of people who are taking them as prescribed, not just those who abuse them.

Ballantyne, who advised the CDC on its soon-to-be-released guidelines, said many people who are taking opioids for chronic pain should have their doses reduced or be weaned off them. But that is not what the CDC guidelines address.

“The CDC guidelines are not there to stop patients who are already addicted. They are there to stop new patients from becoming addicted, patients who should not be taking an opioid in a lot of cases and certainly not in big doses.”

The CDC’s guidelines are intended for primary care doctors, not pain specialists. They provide guidance on pain relief for minor acute pain and long-term chronic pain. They are not aimed at pain management physicians or doctors who treat cancer patients, people at the end of their lives, or patients with severe long-term pain of any kind.

Ballantyne concedes that alternative methods of relieving pain can be much more complicated than prescribing a pill. It often involves a discussion with patients that doesn’t fit easily into a 15-minute office visit.

Patients need to be encouraged to work through the “everyday” pains of aging and minor injuries by staying active, she said. Doctors should suggest doing yoga, listening to music or seeking counseling. “Patients need to be reassured that their pain is not dangerous, and that there is no easy fix.”

NEXT STORY: What’s the Real Cost of Shutting Down Kentucky’s Healthcare Exchange?