Getting Out the Vote From the County Jail

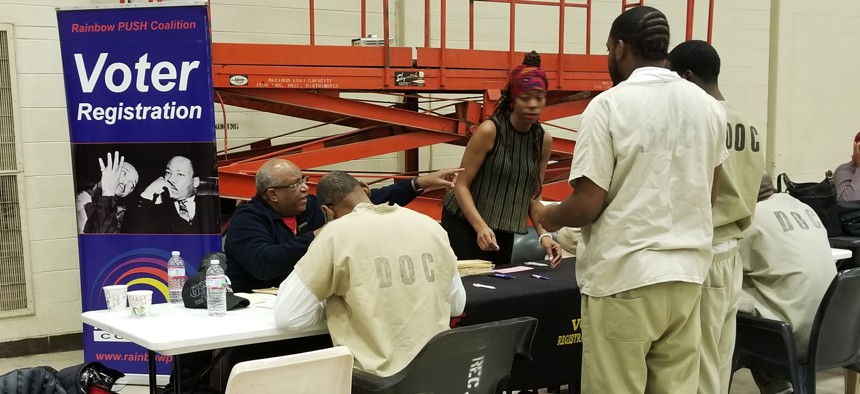

Inmates at Cook County Jail register to vote during Christmas Day services hosted by the Rev. Jesse Jackson in Chicago, Monday, Dec. 25, 2017. AP Photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

In many states, people held without a felony conviction are eligible to vote—but confusion, fear, and a long list of logistical complications often stand in their way.

When Meggen Massey learned that she would be able to vote in the 2016 presidential election, she was “ecstatic.”

She had always thought of herself as a voter, but when she arrived in jail in Los Angeles County with an arson charge, some of her fellow detainees told her that she had lost that right. “I was devastated,” Massey remembered. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, I’m never going to be able to vote again.’”

But that turned out to be wrong. With the help of Susan Burton, the founder of the women’s-reentry program A New Way of Life, and a group of voter-registration volunteers, Massey was able to request and cast a vote by mail ballot.

It’s reasonably common knowledge that most states prohibit people incarcerated for a felony conviction from voting. Twenty-two states also bar people on parole and/or probation, and 12 impose various sanctions that continue post-sentence.

But those restrictions rarely apply to people held in jails, who are usually either awaiting trial or serving time for misdemeanor offenses. Legally, detainees like Massey, who filled out her ballot before she was convicted and sentenced, are still eligible to vote; but practically, confusion, fear, and a long list of logistical complications often stand in their way.

The exact number of people in American jails who are legally permitted to vote is unknown, but it’s safe to say that Massey is far from alone. Chris Uggen, a sociology professor at the University of Minnesota who has studied what he refers to as “practical disenfranchisement,” posits that “a good portion” of the U.S. jail population, which hovers at around 600,000 people, retains the right. Jail populations fluctuate constantly, which makes it especially difficult to pin down an estimate of the voting population inside.

Similarly, it’s hard to know what portion of those eligible voters are not voting because they are unaware of their rights or because their rights are being denied. The 1974 Supreme Court decision O’Brien v. Skinner protects the right of certain inmates to vote in elections without interference from government. But the Court left it up to state and local jurisdictions to decide how exactly to comply with the law.

“There is no national organization that is the anchoring institution to ensure that residents that happen to be in jail on Election Day never lose their voting rights,” said Nicole Porter, who leads state and local advocacy at the justice-reform group the Sentencing Project. Ongoing efforts to help potential voters in jail register or request voting materials “are very grassroots conversations,” she told me.

In reporting this story, I spoke with people running voter-registration, education, and access programs in county jails in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and Texas. Among organizers, “a lot of the work has been focused on trying to expand rights to [disenfranchised] people in tough states, regressive states,” Porter says. “But it calls into question that we don’t really know what’s happening in jurisdictions where people have the right to vote.”

The chief reason for that obscurity is that the process for voting in jails varies widely: from state to state, from county to county, and even institution to institution. For example: In California, Illinois, and Texas, detainees have to submit a voter-registration form and an absentee or vote-by-mail request. But in Massachusetts, people in jail are considered “specially qualified”: They don’t have to register to vote before casting a ballot, though the relevant town clerk has to believe that the would-be voter’s legal residence is accurate.

Other states and counties allow voters to list their place of residence as the jail itself. Michelle Mbekeani-Wiley, a former staff attorney at the Shriver Center for Poverty who led voting efforts in the Cook County Jail, explained that Illinois voters can check a box on their registration form to identify themselves as homeless voters, provided that they include the address of a recognized shelter. Mbekeani-Wiley worked with the county election authorities to ensure that detainees could identify the county jail as their shelter. I asked her if she knew what was happening in the rest of the state. “No, no, we don’t know,” she said. “That would be up to the election authority within that jurisdiction.”

There’s also variability in how quickly cases awaiting trial or other court processes are resolved (and therefore how swiftly people leave jail). That complicates matters for people doing voter-registration work inside: There’s a real possibility that a detainee they’ve signed up might not be there come Election Day. And in some jurisdictions, there’s an extra layer of complexity: Ex-detainees have to re-register to vote once they’re out of jail.

Nitty-gritty legal and policy differences aside, one dynamic was universal across the states and counties I examined: The support of a local sheriff could make or break a voter-registration drive or ballot-request program.

Take Illinois: Mbekeani-Wiley says that access to both registration and the ballot itself is not consistent statewide. That was one of the key reasons she advocated for a recent bill in the Illinois state legislature, HB 4469, that would have required every sheriff and county election authority in the state to come up with a way to enable voting from jail. It also would have required sheriffs to share voting information with people being released from jail, and it would have made the Cook County facility an official polling location.

Sheriff Thomas Dart, a Democrat who has overseen the jail since his election in 2006, supported the bill. “It’s beyond tortured as to why a citizen of [another] county in Illinois, if they’re incarcerated, should have less of an opportunity to vote than someone in Cook County,” he told me.

Ultimately, though, HB 4469 didn’t become law. After a contentious debate on the assembly floor, Republican Governor Bruce Rauner vetoed the bill in August, sending it back to the legislature. “Every citizen eligible to vote should be able to exercise that right, and I fully support this expansion of access to the democratic process,” he wrote. “However, this legislation also mandates that the Department of Corrections, as well as county jails across the state, take part in voter registration and education efforts that exceed the legitimate role of law enforcement, corrections and probation personnel.”

The question of the “legitimate role of law enforcement” is not a new concern in the push to do voter-registration and education programs in jails. After all, a sheriff is an elected official, meaning the person with significant authority over the voting process in jail—not to mention the conditions of detention in the first place—could also be on the ballot. The possibility of a conflict of interest was one of the concerns raised by New York state in the O’Brien case, but it was thoroughly dismissed by Thurgood Marshall in his concurring opinion. “[I]t is hard to conceive how the State can possibly justify denying any person his right to vote on the ground that his vote might afford a state official the opportunity to abuse his position of authority,” Marshall wrote.

Still, that’s not to say that a sheriff doesn’t have real power in structuring how people vote and how they get the information that shapes those decisions. In Cook County, for instance, Dart oversees what gets broadcast onto televisions in the jail’s living units.

Then there are the logistical hurdles presented by a voter-registration or education program. Durrel Douglas, a former prison guard who now leads a voter-rights effort in Houston called Project Orange, suggested his knowledge of correctional safety protocols helped convince officials at the Harris County Jail to permit a registration drive. In his pitch, he laid out a program structure designed to minimize potential challenges for corrections officers. Two selling points: that the volunteers would all be vetted and trained by the county, and that they’d be in and out of the jail in a short window of time.

Some sheriffs have expressed concern about having the staff capacity to support voting programs, particularly in smaller facilities outside of major cities. In Cook County, Dart says the real challenge was sorting out how exactly to orchestrate moving whole tiers of people to and from where the early-voting program was administered. “The smaller jurisdictions, I can see where maybe that would be an issue. But it’s more of a speed bump,” he explained. “It’s just going to be tricky because you’re so small you just have four correctional officers and one sergeant.”

Ultimately, what makes or breaks a program is supportive personnel. “They’re the ones that actually implement,” Mbekeani-Wiley said. “You can have leadership saying, ‘We want to do this,’ but it can fall completely apart if the people actually charged with the task of implementing the policy are not on board.” She noted one crucial moment in particular, when correctional officers in the Cook County Jail go person to person asking if they want to meet with voter-registration volunteers—it could be the first exposure detainees have to the idea of voting.

Perhaps the biggest practical hurdle to in-jail voting is the one Massey ran into in L.A. County: confusion over who’s eligible, which varies from state to state. elly kalfus, who has been organizing voter-registration drives in jails as part of the Ballots Over Bars initiative in Massachusetts, recalled interviewing a formerly incarcerated man who had been involved in prisoner’s-rights work for years—and telling him that his assumption that lifetime parole barred him from the ballot box in Massachusetts was wrong.

Nearly every voter-registration advocate that I spoke to had a similar experience, where detainees hadn’t realized that they were eligible to vote. Interestingly, nearly all of them pointed to the publicity around Florida’s voting-rights-restoration amendment as a major point of misunderstanding. Next week, voters in the state will consider a state constitutional amendment that would restore the vote to people who have completed their sentence, including parole and probation. Currently, Florida disenfranchises felons for life unless they successfully argue their case to the governor and the state clemency board.

Scott Novakowski, a policy director at the New Jersey Institute of Justice, said that many people mistake the Florida law for a national one because it’s on the national news. “Florida gets a lot of attention in the media ... so people here are like ‘Oh, well, you know, I heard on the news that you can’t vote if you’ve ever been convicted of a felony,’” he said.

It’s not just detainees who don’t realize they’re eligible to vote; there can also be confusion on the part of corrections departments, courts, correctional officials, and even voting authorities, according to several people I spoke to. Colleen Kirby, a member of the Massachusetts League of Women Voters who helped detainees request ballots in 2016, described several cases where town clerks weren’t clear on whether they could accept ballots from people held in jail, and had to check with the Massachusetts Secretary of State’s office.

Organizers have added training sessions for public servants and officials to their repertoires. In L.A. County, the Board of Supervisors passed a motion last February that created a countywide voter-registration initiative for people with criminal records. According to Esther Lim, who leads the ACLU of Southern California’s registration efforts in the L.A. County jails, one of the key aspects is training sheriff’s deputies, public defenders, probation officers, reentry personnel, and relevant community groups to understand California’s eligibility requirements and to be able to assist people in filling out a registration form.

Chris Uggen, the researcher from the University of Wisconsin, says that because the jail population skews younger, many detainees have never cast a ballot before and are unfamiliar with the regular voting system, much less what’s available to them inside. Youth and inexperience with voting can create more technical barriers in the registration process, too. Mbekeani-Wiley says that she regularly worked to register 18-year-olds who didn’t know their own social-security numbers.

On top of all that, many would-be voters in jails are concerned about voting improperly—and being prosecuted for it. Crystal Mason is a high-profile case in point: She was on parole in Texas when she voted in the 2016 presidential election, unknowingly breaking Texas law, which prohibits anyone serving time or on parole or probation from casting a ballot. She’s now facing five years in prison for voter fraud. Several other cases in North Carolina have also received national attention.

Not all would-be voters are as excited as Meggen Massey was when she discovered that she had retained her voting rights while in jail. Susan Burton, who runs A New Way of Life Reentry Project in L.A. and is the person who registered Massey, says she sometimes finds “individuals who have completely lost faith in the system” in her registration visits. That’s something Burton, who was once incarcerated herself, understands. I asked her if she had ever thought about voting while she was behind bars. “I cut off everything emotional,” she replied. “I didn’t think about those things. I just tried to get through the time.”

Faced with voter skepticism, Mbekeani-Wiley and Lim both point detainees to the parts of the ballot that have direct effects on the criminal-justice system, like races for district attorney, sheriff, and judicial positions. “I started telling them, ‘You can vote for judges,’ and that is something that sparked a lot of people’s interest ... People who are defendants know who the good judges are,” Mbekeani-Wiley said.

For now, the voter-education options inside jails are limited; detainees often face the challenge of figuring out who and what to vote for without access to a computer, newspaper, or TV. Massey explained that when she registered, she was given a sample ballot, which she said only provided the most basic information about what she’d be voting on. She wanted more. She asked her mother to send her printouts of the information she needed. “I would ask her, ‘Hey, could you look up this proposition that’s going on on this ballot?’ and ‘Can you look these people up so that I know exactly what their positions are and their history?’”

With all these barriers to voting, the number of people who vote from jail is typically modest.

It’s impossible to know what voter turnout in jails looks like across the board given the lack of national data, but county-level numbers provide some detail. To give some examples: In Middlesex County in Massachusetts, Colleen Kirby says that 13 out of the 24 people who requested ballots in the 2016 presidential election submitted them, of a total population of around 800 people. In Cook County, The Chicago Defender reported that 1,200 ballots cast in the 2016 presidential election came from the jail, where the population hovers at around 7,000. And in Houston, Durrel Douglas said that 29 people out of the 662 they registered ended up casting a ballot in this year’s primary elections.

But, as Esther Lim points out, the voting population inside jails could have considerable electoral impact, particularly on tight races. “There are 17,000 people incarcerated [in the L.A. jail system] and over 10,000 who are actually eligible to register,” she says. “Say, for example, all 10,000 registered. I mean, they could really swing an election.”

And if some of the felony-rights-restoration campaigns, like the one in Florida, succeed, knowing exactly who is eligible to vote could get even more complex, as detainees and officials play catch-up with an evolving status quo.

Which direction would such an election swing? Chris Uggen, who has researched how different felon-voting laws in Florida might have affected the outcome of the Bush-Gore presidential election in 2000, says it’s “not straightforward” to determine how the jail population might vote. But he did add that “the jail population tends to be very low income and is drawn disproportionately from communities of color,” characteristics that tend to skew Democratic.

But if the actual numbers of people voting from jails are small, the symbolic power of their vote is not. Mbekeani-Wiley called it “a glimmer of hope in a very trauma-filled environment”: “You get to demonstrate that you participated in the political process, and you’ve exercised power despite being in such a powerless place.”

It has weighty historical meaning, too. The practical disenfranchisement of voters in jails is another chapter in what Nicole Porter called the “long history of undermining voter participation in the United States,” and especially of denying or discouraging people of color from voting. That includes some of the first felony-disenfranchisement laws, which were part of a host of post-Civil War restrictions aimed at preventing newly enfranchised African Americans from voting. It’s no wonder that the myth that people who are behind bars can’t vote is hard to shake—and why any single vote from jail is remarkable. “It’s something their ancestors have fought and died over,” Mbekeani-Wiley says.

There’s a practical societal dimension here, too. Some academic research, from Uggen and others, suggests that voting correlates with lower recidivism rates. That’s not the same as causation, Uggen cautions, but he does believe that voting is a positive experience. “I don’t think it’s some magical act of pulling the lever or filling in the little dot on the form that transforms the individual,” he says. “It’s more that voting is an expression of identification with the community and standing shoulder to shoulder with your fellow citizens.”

That’s how Meggen Massey seems to look at it. Because she’s on parole after serving her sentence, she’s unable to vote in California. But she will be again once her parole is up. “Now if we can get it to where I can serve for jury duty—that would be great, too,” she told me. “We all have a civic duty, and I want to be part of that.”

Margaret Barthel is a producer-reporter at WAMU-88.5 and a former producer at AtlanticLIVE. This article was originally published in The Atlantic.

NEXT STORY: Mayor Deployed to Afghanistan Killed in ‘Apparent Inside Attack’