Detaining Refugee Children at Military Bases May Sound Un-America, But It's Been Done Before

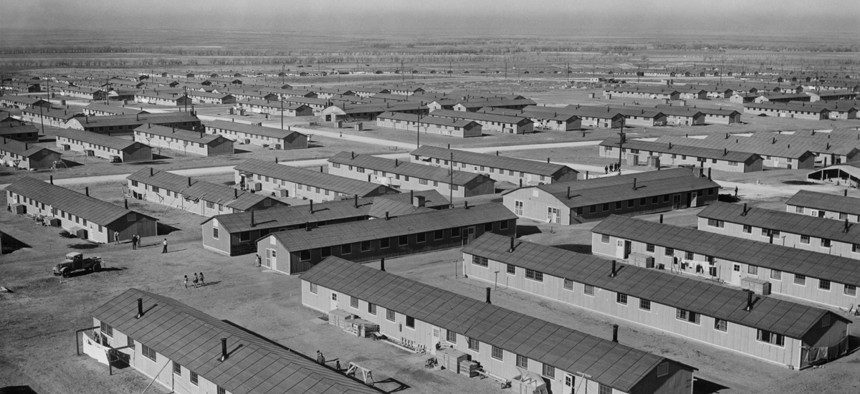

Japanese internment camps during World War II. Everett Historical/Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | Although the country hasn’t often had to cope with so many unaccompanied child migrants, the U.S. government has repeatedly turned to military bases to shelter unexpected migrant populations.

Fort Sill, an army base in Oklahoma, will soon become a refugee camp. The Department of Health and Human Services expects the repurposed military facility to house up to 1,400 unaccompanied migrant children from Central America by early July.

Border agents apprehended 54,000 unaccompanied child migrants at the Mexico border last year alone. Typically, the government houses such children in temporary shelters and then places them with relatives already living in the United States. This means children can live with family and communities, rather than protective custody, as they wait for their asylum hearings.

This isn’t the first time the U.S. has housed kids at a military base, though. Fort Sill was used by President Barack Obama’s administration to shelter 1,800 Central American migrant children for four months in 2014.

Although the country hasn’t often had to cope with so many unaccompanied child migrants, my research on refugee camps in America reveals that the U.S. government has repeatedly turned to military bases to shelter unexpected – and often undesired – migrant populations. At different times throughout the 20th century, the federal government kept groups of people from Hungary, Vietnam, Cuba and Haiti on U.S. military bases.

The result can be either efficient immigration processing or a prolonged, confined and traumatic experience. It all hinges on the federal government’s refugee policy, its commitment to resettlement and on broader American views of the migrant population housed at the base.

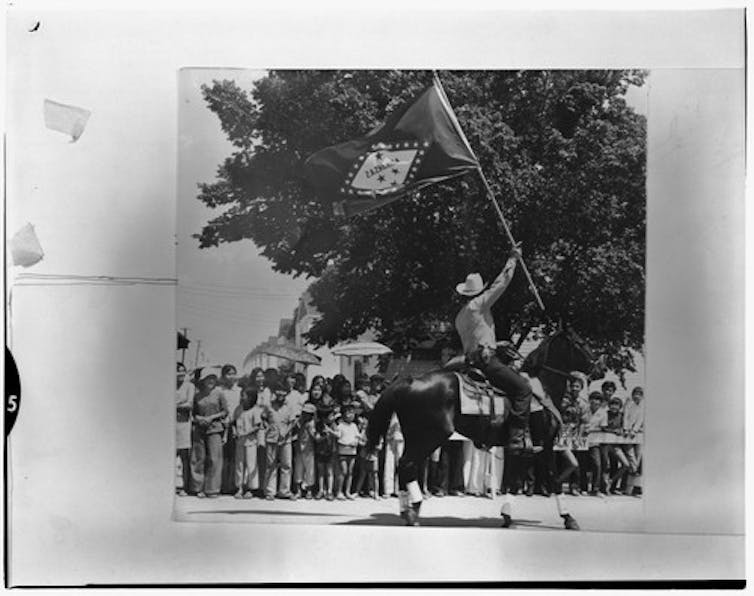

1975: Vietnamese Arrive to Fort Chaffee

Fort Chaffee, in Arkansas, is an informative example of the outside influences that can help or hurt the success of refugee camps in the U.S.

Established in 1941 as a military training camp, Fort Chaffee gained importance after the final U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam. It was one of several military bases selected to receive 120,000 South Vietnamese fleeing their country as the North Vietnamese marched into Saigon.

In April 1975, approximately 50,000 Vietnamese arrived in Fort Chaffee.

Then, as now, the sudden arrival of so many foreigners divided Americans. Some felt generosity and compassion toward the Vietnamese migrants; others expressed anti-refugee sentiments and fear of invasion.

“The people of Arkansas might as well realize what they are sacrificing, bringing these people over to this fertile country,” wrote one local man to Arkansas’ Southwest Times Record on May 4, 1975. “The day will come when there will be booby traps in the Ozarks.”

The letter writer, a Vietnam War veteran, saw the Vietnamese at Fort Chaffee as his enemy – not as U.S. allies who faced reprisals as a result of the United States’ war.

“[W]hen I went over there … I was going to keep them from getting closer to the United States,” he wrote. Instead, he added, “they almost beat me back here.”

Ford Welcomes the Vietnamese at Fort Chaffee

President Gerald Ford and American military leaders felt responsible for their Vietnamese allies displaced by the U.S. war.

The federal government admitted Vietnamese outside regular immigration channels and worked to resettle them in the United States. Ford even visited Fort Chaffee to greet the new arrivals in August 1975.

“It’s really inspirational to see so many young people, old people and others getting an opportunity to be a part of America,” he said. “We’re proud of them and welcome them all here.”

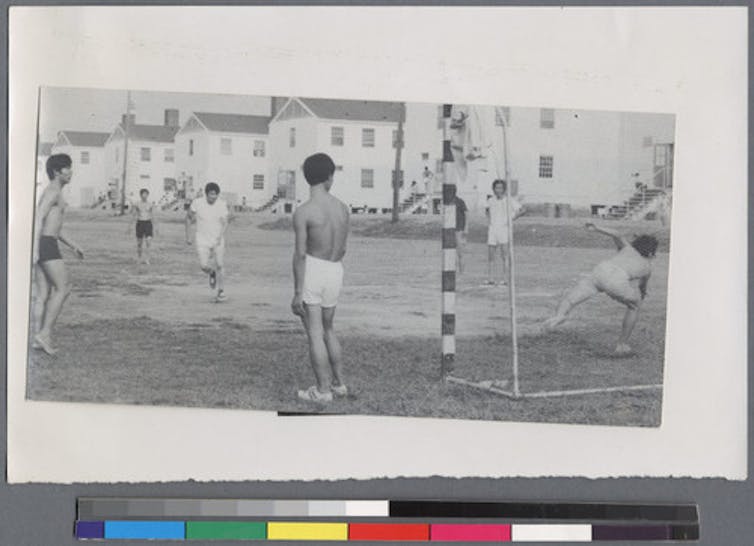

Fort Chaffee offered English classes, basic cultural orientation lessons and spaces for religious worship to the Vietnamese held there. And the U.S. military worked with volunteer agencies to ensure they were quickly sponsored and resettled.

By December 1975, less than a year after their arrival, all 50,000 Vietnamese were living outside the base.

1980: Cubans Harassed at Fort Chaffee

The base would be full of migrants again soon enough.

In 1980 approximately 100,000 people fled Cuba when President Fidel Castro – facing internal domestic pressure – briefly allowed people to leave the communist island from the Mariel Port.

Cubans from the Mariel Boatlift were more likely to be working-class and Cubans of color than the generation who fled after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Along with political dissidents and those seeking better economic opportunities, Castro also forced “undesirables” off the island, including those deemed to be criminal, mentally ill or gay.

By flooding American shores with these highly stigmatized Cubans, Castro created a political problem for President Jimmy Carter.

Carter believed the U.S. had an obligation to “provide open heart and open arms to refugees seeking freedom from Communist domination and economic deprivation.”

But many Americans saw the new arrivals as dangerous and unwanted.

Bill Clinton, then the governor of Arkansas, warned federal officials that sending Cubans to Fort Chaffee would be unpopular and possibly volatile.

He was right. In May 1980, locals from around Fort Chaffee met the approximately 20,000 Cubans who arrived there with hostility. Ku Klux Klan members even protested outside the base and “rant[ed] about white power,” according to a 1980 People Magazine article.

The Cubans sent to Fort Chaffee also resented their detention in what one government official called “a concentration camp atmosphere.” On June 1, 1980, hundreds of them protested and burned down base buildings. Many then walked off the base toward town.

The Cubans threw rocks and bottles, and fighting broke out. Dozens of Cubans and Arkansas state troopers were injured.

Since it was difficult to find sponsors for many of these Cubans, hundreds stayed at Fort Chaffee much longer than the Vietnamese – in some cases over a year.

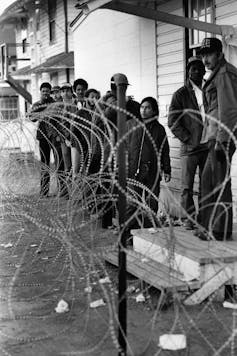

Over time, life at the military base became more restrictive.

“It’s hard to describe the place as something other than a prison,” the Boston Globe reported in 1981. “There are guards, fences; Cubans can’t leave the perimeters.”

The roughly 400 Mariel Cubans who had not found sponsors by February 1982 were transferred to federal prisons. Some were later released; many others languished in prison in legal limbo.

Refugee Camp or Military Prison?

The history of Fort Chaffee shows that it’s risky to house refugee populations on a military base.

Executed with compassion and the promise of resettlement, it can facilitate shelter, social services and a quick transition.

Done badly, when anti-refugee sentiment is high, a military base can become prison-like – a place where migrants are confined behind barbed wire, with unknown release dates.

The Trump administration’s stated policy toward refugees is to deny them asylum and deport them as soon as possible. That includes children.

It is unclear whether the young migrants sent to Fort Sill will have access to lawyers, education or social services.

In this political context, warehousing children at a military base seems ripe for lawsuits, unanticipated consequences and trauma for the children trapped there.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jana Lipman is an associate professor of history at Tulane University.

NEXT STORY: New Laws Help Rural Black Families Fight for Their Land