Supreme Court’s Gerrymander Decision Shifts Fight Back to States

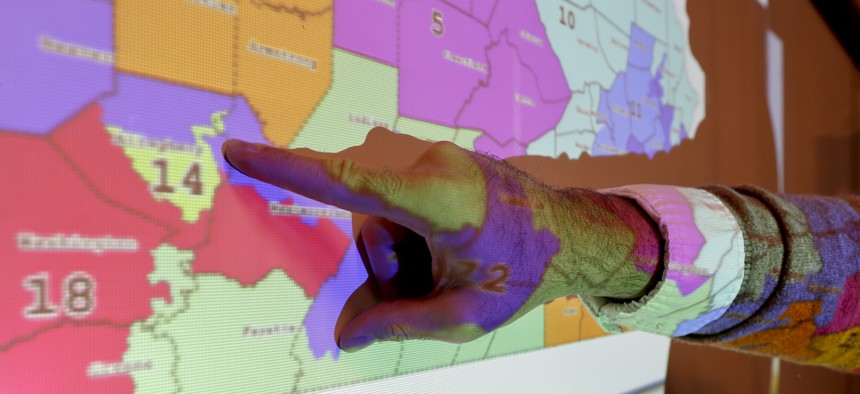

William Marx points out one of the districts that crossed four counties as an image of the old congressional districts of Pennsylvania are projected on a wall in the classroom where he teaches civics in Pittsburgh on Friday, Nov. 16, 2018. AP Photo/Keith Srakocic

Connecting state and local government leaders

Reformers are likely to focus on independent commissions and transparency efforts to overhaul partisan gerrymandering before maps are redrawn in 2021.

The Supreme Court’s decision this week not to rein in partisan gerrymandering has set the stage for activists and legislators to ramp up redistricting efforts at the state level.

Reformers say they are likely to focus on campaigns to make the redistricting process more transparent or to push for independent commissions, rather than lawmakers, to oversee the next drawing of congressional maps. But to do so, they will have to head off political parties primed to use the system to their advantage.

“You think it’s bad now, it’s going to get worse,” said Daniel Tokaji, a constitutional law professor at Ohio State University. “Up until now state legislators, if they’ve been smart, have at least had to have some sort of pretense that they are doing this for a neutral reason, like to promote compactness or keep communities of interest together. All that is going to go out the window in the next round of redistricting.”

In its 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court found that while “excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust,” federal courts do not have the authority to weigh the constitutionality of gerrymandering.

“Federal courts are not equipped to apportion political power as a matter of fairness, nor is there any basis for concluding that they were authorized to do so,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts for the majority.

The high court had been asked to examine the political processes behind the redrawing of congressional districts in North Carolina, which benefitted Republicans, and in Maryland, which helped Democrats.

States redraw the districts used to elect state and congressional representatives every 10 years, following the census. The task typically falls to state lawmakers and governors, and Republicans earned advantages across numerous states thanks to the last round of redistricting in 2011.

Though the federal courts are now out of the process, the fight over gerrymandering is hardly finished.

“This is not the end of our fight,” said former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, now finance chairman of the National Republican Redistricting Trust. “Democrats will double down on flipping state supreme courts and bring more lawsuits to be heard by friendly judges they helped to elect—just like they have already done in Pennsylvania and North Carolina and tried to do in Wisconsin.”

Former attorney general Eric Holder, who now leads the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, on Thursday outlined efforts he and other Democratic leaders are already engaged in to break up gerrymandered districts established in 2011. Those include litigation, reform efforts, electing candidates “who support fair maps” and grass-roots advocacy, he said.

Activists say they plan to pursue remedies through state courts and legislation, including advocating for the establishment of independent or bipartisan redistricting commissions.

Voters in five states spanning the political spectrum—Ohio, Michigan, Colorado, Missouri and Utah—passed ballot initiatives in 2018 addressing partisan gerrymandering. This year legislatures in New Hampshire and Virginia also passed bills to establish redistricting commissions.

Yurij Rudensky, an attorney with the Brennan Center for Justice who focuses on redistricting issues, said state-level action shows voters are increasingly engaged on gerrymandering. In the wake of the Supreme Court decision, more states are likely to consider establishing independent commissions, he said. But it’s doubtful new panels would be up and running in time to oversee the next map redrawing in 2021.

In the meantime, states might seek to make their redistricting process more transparent.

“Sunshine really disinfects the process,” Rudensky said.

The Brennan Center plans to develop model guidelines for establishing independent redistricting commissions and redistricting transparency in the fall that can be used by states looking to overhaul the process, Rudensky said.

But not all states have a ballot initiative process, and those that don’t may have to turn to state courts instead to take on gerrymandering concerns.

In North Carolina, one pending lawsuit was already challenging the legality of district lines used to elect state representatives before the Supreme Court ruling. Because the state does not have a ballot initiative process, the effort to reform redistricting “is going to be largely court-driven,” said Dustin Chicurel-Bayard, spokesman for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice.

“It’s clear that this fight is far from over and there are remedies for fighting partisan gerrymander. But it’s going to be on the state level,” Chicurel-Bayard said.

Andrea Noble is a staff correspondent for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: States Authorize Ridesharing for Medical Transport