Drilling Deeper Wells is a Band-Aid Solution to Groundwater Woes

Researchers argue that we can't infinitely drill for water. Theeraphong/Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | Although this seems like a logical response when usable water supplies are scarce, deeper drilling cannot go on forever.

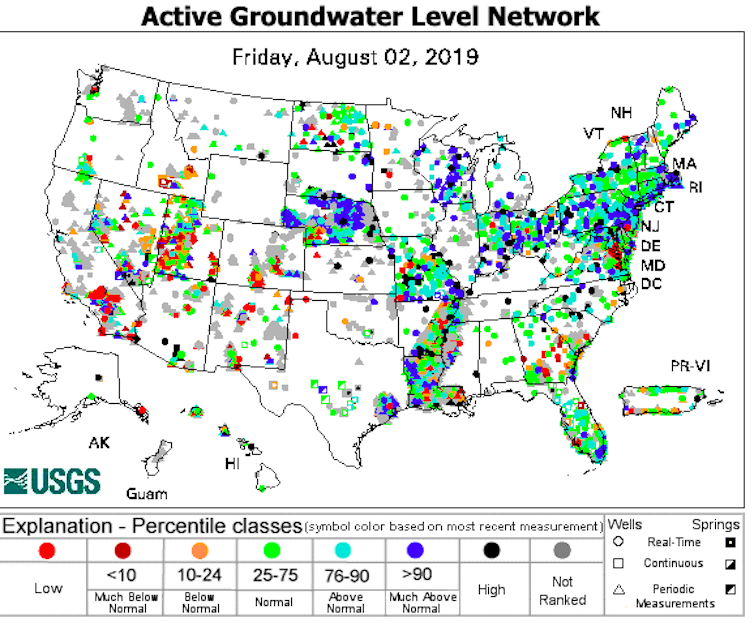

With memories of the wettest U.S. spring on record still fresh, it seems strange to hear that in many parts of the nation, groundwater supplies – the water stored underneath our feet, in rocks and sediments – are lower than normal. This includes places with wet climates, such as southern Georgia, coastal Maryland and Cleveland.

How is this possible? Although groundwater and surface water interact, they differ in key ways, including the processes through which rain and snowmelt replenish them. Because groundwater supplies drinking water to more than 120 million Americans, provides nearly half of all water used for irrigation and is used for industrial purposes such as energy production, it is a critically important resource.

Until recently, no one had mapped groundwater well locations and information across the nation. We are a water resources engineer with training in water law, and a water scientist and large-data analyst. In a recently published study, we produced the first map of groundwater wells across the United States, and show that groundwater wells are being drilled deeper than ever. Although this seems like a logical response when usable water supplies are scarce, we see deeper drilling as a band-aid solution that cannot go on forever.

Why Map Groundwater Wells?

Our map of wells highlights how important groundwater is to U.S. livelihoods. From coastal California to the tip of Long Island, and from the semi-arid plains of eastern Washington state to the humid Florida Keys, people rely on groundwater for all sorts of daily activities.

As climate change intensifies, groundwater is likely to become even more important because it is generally more resilient to climate variations than river flows are. But unlike rivers and the dams, levees and spillways people have built to control them, groundwater is hidden. Groundwater wells are small, widely distributed and often out of view.

Our goal was to make this unseen resource visible by mapping where Americans are pumping groundwater from wells. Groundwater is a finite resource. In our previous research with Grant Ferguson and Jennifer McIntosh, we highlighted that only a limited share of groundwater is fresh enough for drinking and irrigation.

To put this earlier work into context, we wanted to map the abundance of groundwater wells nationwide. What we didn’t expect was that it would take us more than four years.

A Labor of Love and Curiosity

In the U.S., groundwater use is regulated mainly at the state level. Many states do not require groundwater metering, monitoring or reporting, so they have limited information about groundwater use.

There is no national standard or requirement for collecting information about groundwater wells, and a handful of states either do not collect well data or do not make it publicly available. Where data are collected, it may be handled by a statewide agency or by county or regional agencies.

As a result, information about U.S. groundwater wells is scattered among more than 60 different databases, each with their own categories of interest and each with different levels of completeness. We worked with all of these agencies to understand what information they had and the limitations of their data.

We received a wide array of responses from different agencies, which in our view reveals a need for a nationwide standard and database for reporting well construction. Each agency we collected data from had a tremendous amount of knowledge about local groundwater resources, but not all of this information had been compared to other areas.

We stitched together this information to create a comprehensive picture of groundwater wells that transcended jurisdictional boundaries. Our analysis shows that between 1975 and 2015, the trend was to drill wells increasingly deep in 70% of the areas we analyzed across the nation. Because we used locally relevant information, we can zoom in and examine any region of interest. For instance, we found deeper well construction over time in 80% of areas within the Colorado River Basin, a higher rate than the national average.

Why Drill Deeper?

There are many reasons why people may be drilling increasingly deep wells, and they don’t all imply doom and gloom. For example, deeper wells may be the result of improved well and pump technologies; discovery of deeper fresh groundwater reserves; different permit requirements for shallower versus deeper groundwaters; inadequate water yields in some layers; or poor water quality at shallower depths.

Nonetheless, we do not see drilling deeper as a sustainable path forward. In some places it is impractical because wells drilled into deeper rocks cannot pump water at a sufficiently high rate. Moreover, deep groundwater is often saltier than much of the overlying groundwater. In these areas, drilling deeper can result in pumping salty water.

Even if good groundwater is available at deeper levels, accessing it may not be affordable. A typical domestic groundwater well in central California costs tens of thousands of dollars, and a typical agricultural well costs hundred of thousands of dollars.

We conclude that improving groundwater governance and protecting the quality of our deep groundwater will become increasingly important if wells continue to be drilled deeper. Our map of American water wells highlights how important groundwater is for households, farms and industries from the arid west to the humid east. Protecting it from pollution and overuse will help to ensure future generations have access to reliable and high quality groundwater resources.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Debra Perrone is an assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Scott Jasechko is an assistant professor of water resources at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

NEXT STORY: Pregnant But Hours From a Hospital? A Push to Examine Rural Maternal Health