Attack traffic from China takes a great leap forward

Connecting state and local government leaders

Cyberattack traffic originating in China took a sharp jump in late 2012, according to the latest analysis of activity on Akamai’s global content delivery network.

Chinese law prohibits hacking and the Chinese military does not engage in online sabotage and espionage, according to official statements by the Chinese government.

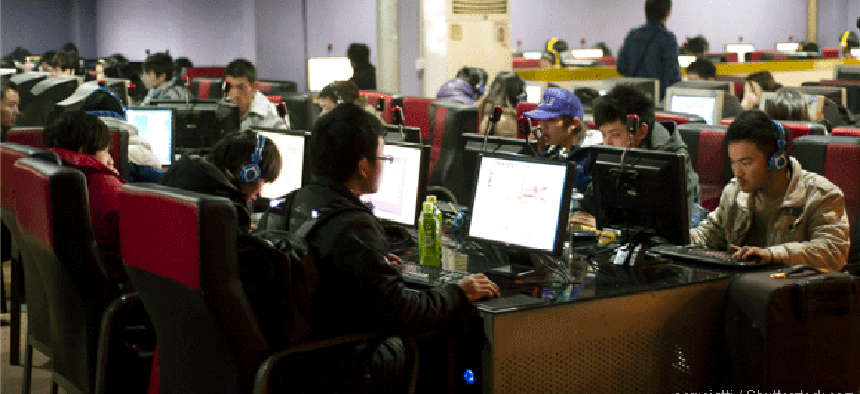

But somebody in China is doing a lot of hacking. Attack traffic from Chinese addresses jumped sharply during the third quarter of 2012, accounting for a full third of attacks identified on Akamai’s global content delivery network, which delivers online resources for many federal agencies.

The figures were released several days before the New York Times reported that it was the victim of a sophisticated long-term effort by Chinese hackers to gain access to reporters’ information and credentials. It said the attacks were part of a broad online espionage program targeting western journalists dating back to at least 2008.

Chinese officials characterized the accusations of involvement in the Times attacks, first noted in October, shortly after the time covered in the Akamai report, as “groundless” and “irresponsible.”

There are limitations to what analysis of attack traffic can tell about the attackers.

“We don’t have end-to-end visibility,” said David Belson, editor of the Akamai report. “We only know the IP address making the connection to us. But many of our statistics are nominally in line with data gathered by others.”

Because it is easy to cross national boundaries on the Internet and acquire — legally or illegally — the resources of servers and computers in other countries, the connecting IP address does not necessarily show the actual location of the attacker. But other research has found that, along with the high amount of malicious traffic originating in China, there is evidence that a lot of malicious code also originated in that country. The Times investigation found that the pattern of attacks matched others that had been traced to China.

Akamai’s data is culled from traffic on its network, which delivers a large percentage of the world’s Internet traffic (averaging nearly 21 million HTTP hits per second on Jan. 31). Many agencies use the network to deliver content efficiently, rather than maintain bandwidth needed to support spikes in demand. The distributed system of servers also provides additional security against denial of service attacks.

The jump in malicious Chinese traffic was unexpected, Belson said, although China historically has been the top source, and the overall rankings of top 10 source countries remained unchanged from the previous listing. The United States is the No. 2 source of attack traffic, with its share inching up from 12 percent in the second quarter of 2012 to 13 percent in the third. But over the same time, China spiked from 16 percent to 33 percent.

“That definitely is surprising,” Belson said.

The number of countries observed generating attack traffic dropped from 188 the previous quarter to 180 in the third quarter of last year. At the same time, the attacks became more varied in the ports they are targeting. In the first quarter of 2012 the top 10 ports accounted for 77 percent of attacks, but dropped to 62 percent in the second quarter and to 59 percent in the third.

The most commonly attacked ports are 445, for Microsoft Directory Services (30 percent of observed traffic) and 23, for Telnet (about 8 percent). The good news is these attacks can be addressed by firewall configuration. “An organization should not have these ports open to outside connections,” Belson said.