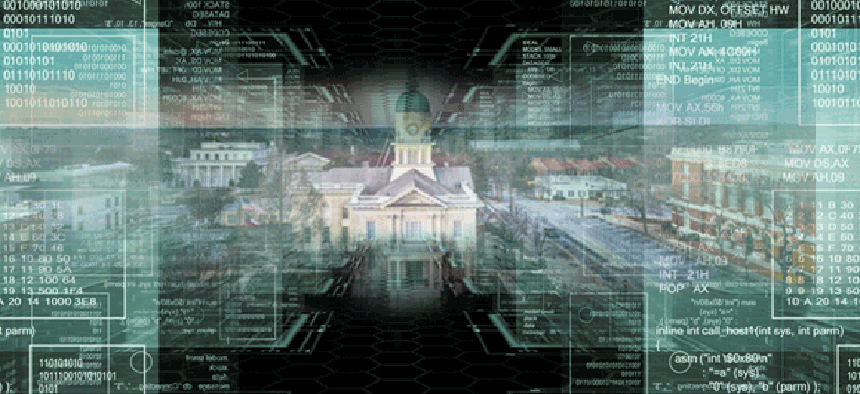

In virtual town of Alphaville, students prep for cyber sieges

Alphaville is part of the Michigan Cyber Range, a network and classroom training environment designed to prepare IT managers on cybersecurity attacks and defenses.

The small town of Alphaville, Mich., is under attack. Up to 50 hackers are trying to shut down the power grid. The local library is being used as a backdoor attack point against city hall. There's an encrypted bug being planted on the local elementary school's mainframe, and residents are finding that their desktop computers are being turned into zombie clients, further compromising security in this normally quiet village.

Thankfully, Alphaville only exists electronically. It's a collection of virtual machines and computers networked together and assigned security levels modeled on how real towns across the country are actually configured. It exists as part of the Michigan Cyber Range, a network and classroom designed to enable the testing of cybersecurity attacks and defense methods in as realistic an environment as possible.

Director of the Cyber Range Joe Adams explained that creating the facility was part of the state's Cyber Initiative launched last fall by Gov. Rick Snyder. "There are many states that put a focus on different aspects of technology, like Maryland with the federal government or California with Silicon Valley," Adams said. "We want Michigan to become the place where people come to learn how to protect the critical infrastructure."

Adams served in the military and used that experience to help build the Cyber Range and give it a real sense of place. He said he based Alphaville on the façade-like training towns set up on military bases around the country, only instead of learning squad tactics and weapons, Alphaville trainees are learning how to secure and protect critical infrastructure like power grids, hospitals, local government installations and small businesses.

One thing that makes the range unique is that it's a totally unclassified facility, meaning that while the latest attacks and defenses can be studied, it remains open to everyone from government and private industry.

"About 85 percent of all critical infrastructure in this country is protected by civilians, not feds," Adams said. "By keeping the facility unclassified, it allows anyone to be able to schedule training here. And those groups can bring in people who need to learn the latest defenses, everyone from foreign nationals to first responders, without making them go though a long process of security clearance."

Alphaville is designed to be just like a real town in terms of the cyber infrastructure and how buildings and organizations are networked. Its centerpiece is the Alphaville Power and Electric Company, where a realistic infrastructure is in place that allows students to see how power grids are configured and managed, from the generating plant to substations and down into individual homes.

Inside those structures, unique protocols, vulnerabilities and security challenges are demonstrated, including requirements for how to secure a SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) environment replete with sensors, human-machine interfaces and corporate networks.

This is tied into a 3-D world generator so that students can see the consequences of their actions as if they were looking in on a real town. "If something happens to take down the power grid, the students can actually see the lights go off in town and the citizens walking around in the dark," Adams said.

The K-12 school network, on a Web-accessible server farm, features classrooms and computer labs, staff email, human resources applications and personal information about students. Alphaville’s public library has an online card catalog and asset management system in addition to publically available workstations. The Alphaville city hall features a public-facing website, a secure portal for authorized users and an internal network with legal documents, personal information, and other sensitive material. There’s even a small retail business called Zenda, Inc.

Each location is created using virtual machines set to a designated security level, giving students a chance to see how information systems are connected. Most of the government buildings are linked through a town network demonstrating that a hack into a low security installation like a school could act as a backdoor to the city hall network, using spoofed or captured credentials.

Currently, the Michigan Cyber Range offers two distinct types of classes with exercises that can be performed in Alphaville. The first is a Red versus Blue scenario in which two teams are pitted against one another. One team uses the latest attack techniques to try and do as much damage to Alphaville as possible, while the other team attempts to defend the town.

A Paintball exercise has multiple teams attacking the town in an attempt to secure a beacon within a critical system, fortify it and move on in a capture-the-flag type of scenario. This not only trains students to think like hackers, but it also teaches them how to outfox the enemy, using techniques like following a network intruder to learn his technique and attacking only after gathering valuable intelligence.

At a ribbon cutting ceremony in March, the expansion of the range onto the grounds of the 100th Airlift Wing National Guard Base was celebrated with a major cybersecurity warfare effort that pitted teams in Michigan against both the California National Guard and students at the West Point Military Academy for control of the town.

Gov. Snyder attended the event to see how that arm of the state's Cyber Initiative was proceeding. "Most people won't recognize the value of what's being done today. It is not a crisis yet," Snyder said. "Let's not be on the defensive. Let's make sure we have that defense in place when it's needed."

The range is in the process of bringing a new computer forensics class online. In that exercise, an attack has already taken place, and the teams are tasked with finding out how the hacker got into the network, discovering what if anything was left behind, sealing gaps so that systems can no longer be exploited and uncovering clues as to the identity of the perpetrator.

The town of Alphaville is also expanding. Adams says that a virtual hospital is in the works, where students can learn the intricacies of working with HIPAA-protected health information.

Much of the advanced cybersecurity work in Michigan is being conducted by a non-profit corporation owned and governed by Michigan's public universities. Called the Merit Network, it was formed in 1966 when universities there began to build and deploy the first routers to network their mainframes. Today the Merit Network has over 350 members including many state and local governments, schools and libraries, and even extends north into Canada. It is also made up of hundreds of miles of fiber-optic cabling that make efforts like, and access to, the Michigan Cyber Range possible.

The Merit Network also runs Alphaville. In a way, Adams is a bit like the mayor of that fictional town, and he's pleased when it can be used to improve cybersecurity across the country, especially in critical infrastructures, which are often overlooked and guarded by civilians.

"We are trying to train across industry, so more people can be aware," he said. "This is another opportunity for Michigan to set a high standard for cybersecurity training inside the state, across the nation and with our international partners."

Anyone interested in training at Michigan's new range can head over to the range's home page to see a class schedule and register for training. Adams also said that special classes were available if a group needed specific training or exercises surrounding a certain area of security.

NEXT STORY: Takeaways from Verizon's data breach report