States crack down on driver's license fraud

Connecting state and local government leaders

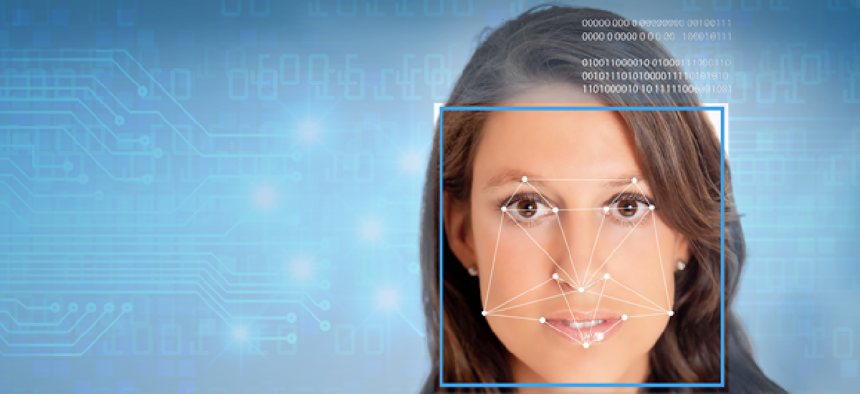

States increasingly are employing facial recognition software to compare driver’s license or ID photos with other images on file.

This article originally appeared in Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

One driver, one license, that’s how it’s supposed to be. But some fraudsters or drivers with serious violations try to beat the system by getting multiple licenses using different names.

The implications of the deceit are far-ranging: People use driver’s licenses and state IDs to do everything from cashing checks to opening bank accounts to boarding domestic flights.

States increasingly are foiling the crooks and scam artists by employing a high-tech tool: facial recognition software. The software uses algorithms of facial characteristics to compare driver’s license or ID photos with other images on file with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV).

At least 39 states now use the software in some fashion, and many say they’ve gotten remarkable results. In New York, thousands of people with false identities have been arrested, and even in the less populous state of Nebraska, hundreds have. Two states – New Jersey and New York – are now working together on a project to identify certain types of violators, a step that other states may follow.

“You have an opportunity, using this technology, to find people who are trying to skirt the system,” said Geoff Slagle, director of identity management for the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA). “It has really helped to identify fraudsters.”

But critics raise concerns about privacy invasion and potential abuse. While photo database access is limited to the DMV in some states, others allow sharing with law enforcement.

For a long time, it was hard for states to crack down on identity thieves and fraudsters, given their lack of manpower. But officials say that has no longer been the case since they started using facial recognition. Among the cases uncovered in the last two years:

In New York, a sanitation worker was charged with impersonating his dead twin brother and collecting more than $500,000 in disability benefits over 20 years.

In Iowa, a fugitive who escaped from a North Carolina prison while serving time for armed robbery in the 1970s was identified when he tried to apply for a driver’s license using another name.

In New Jersey, a man was charged with using false identities to get two fraudulent commercial driver’s licenses to drive trucks. His licenses had been suspended 64 times, including six times for DUI convictions.

“A driver’s license is a strong, dependable form of ID,” Slagle said. “We want to make sure the people who are getting the licenses are who they claim to be.”

Detecting fraudsters

Many officials say facial recognition has made a difference in their ability to detect and deter fraud and abuse.

“It’s not a panacea, but it’s another great tool in our arsenal to tie the driver to the record,” said Raymond Martinez, chairman of New Jersey’s DMV. “Our goal is one driver, one record. We have to be able to know that an individual can’t just game the system and get a license under another name.”

Here’s how facial recognition works: When someone applies for a driver’s license or ID, a photo is taken and the image is converted into a template created from the person’s unique physical features, such as cheekbones or the distance between eye pupils. An algorithm compares the image with others in the database, searching for a possible match.

If analysts discover that the image is associated with two or more identities, they try to figure out why. Sometimes, it’s a clerical error or the result of a name change after a marriage or divorce.

Often it’s a deliberate attempt to violate the law. If fraud is suspected, the department investigates and can take administrative action, such as a license suspension. Agencies that have their own investigative unit with arrest powers can also conduct a criminal probe; those that do not can turn the case over to an outside law enforcement agency.

State officials say people seek more than one license for a number of reasons. Some want to stay behind the wheel despite having lost their driving privileges due to multiple serious violations, such as DUIs. Others want to obtain credit, buy a car or get a mortgage using a stolen identity. Still others are wanted felons or criminals, such as sex offenders, who are trying to hide their identity by using an alias.

“The driver’s license is the gateway to everyday interaction,” said Ian Grossman, vice president of member services for AAMVA, the motor vehicle administrators group. “If someone has a legitimate license from an issuing authority under false pretenses, it empowers them to do bad things.”

Facial recognition has led to numerous arrests and administrative actions against drivers.

In New York, where the technology was adopted in 2010, the DMV has identified 14,500 people with two or more licenses, all fraudulent, said Owen McShane, that agency’s director of investigations. Some date to the 1990s and are too old to prosecute.

McShane said his agency has taken administrative action against 9,500 people and arrested 3,500 more. They include a man who was a fugitive for 17 years after robbing a bank and a woman who collected nearly $525,000 in fraudulent disability benefits.

In New Jersey, Martinez, the DMV chairman, said officials have referred about 2,500 fraud cases to law enforcement since 2011. More than half couldn’t be prosecuted because the statute of limitations had expired. They also cleaned up more than 12,500 clerical errors.

New York and New Jersey are working on a pilot project that uses both states’ photo databases to pinpoint drivers with commercial licenses who have had multiple violations and are getting licenses with phony identities and crossing state borders. Martinez said it’s the first state-to-state project, but he suspects others will pick up on it.

Privacy concerns

Some privacy groups are concerned that law enforcement could misuse the photos in the databases. For example, they say, the technology could be used to identify people at political rallies.

“The use of facial recognition has implications for privacy and civil liberties and it should be part of a public debate in order to properly limit its use and mitigate the privacy risks,” said Jeramie D. Scott, national security counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a public interest nonprofit.

Some states have taken steps to limit access to the database and to keep the information in-house.

“That is a good step. But it’s inconsistent,” he said. “Right now, it’s the Wild, Wild West because there is a lack of legal rules regarding the use of facial recognition in the states and at the federal level, generally speaking.”

Laws or policies governing whether DMVs share their information with outside law enforcement agencies vary. AAMVA’s Slagle said that his group, in a May survey of all states plus the District of Columbia, found the overwhelming majority of departments using the software do not allow direct access to their databases. Still, more than half said they assist law enforcement agencies with criminal investigations by performing the searches themselves.

In Vermont, for example, the DMV searches its database for law enforcement agencies conducting a criminal investigation if it gets an official request. But no one outside of the department is allowed access to the database, said Capt. Drew Bloom, who heads the investigations division there.

Bloom said the technology has had an impact since it was introduced in 2012. “It pretty much killed the identity theft business here,” he said. “We rarely have them now, and we used to get them all the time.”

In Washington state, DMV officials have tougher restrictions. They do not share information from their database without a court order.

Some states take a different approach.

In Iowa, most law enforcement agencies can request that the DMV search its database. But this spring, the Department of Public Safety, which runs the state patrol and the Department of Criminal Investigations, gained direct access, said Paul Steier, the Iowa Department of Transportation’s investigations bureau director.

In Nebraska, the state patrol and the Omaha and Lincoln city police departments can access the facial recognition system, said Betty Johnson, an administrator for the DMV there. All three departments have a user ID and password and can load an image and perform their own searches.

Johnson said her agency started using facial recognition in 2009. Since then, about 3,000 people have been prevented from getting a license and more than 300 have been arrested.

Johnson said that while it’s important to protect Nebraskans’ privacy, sharing information with law enforcement leads to safer roads and communities.

“If government agencies are not allowed to work with law enforcement, they’re really tying our hands, as far as protecting the public,” she said. “Facial recognition technology is helping protect people not just from identity theft and fraud, but as drivers and as neighbors.”

NEXT STORY: Grid security as a service?