The newest cyber risk: Hackers can hear what you're printing

Connecting state and local government leaders

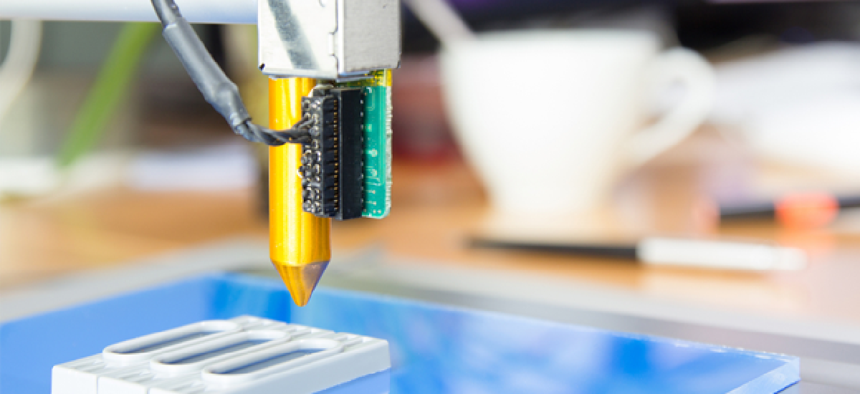

Using only a smartphone, researchers were able to get enough information from signals created by a 3-D printer’s nozzle to reverse-engineer the object being manufactured.

3-D printing has shown its utility in recent years, tapped by NASA to construct tools for astronauts, by the National Institutes of Health to create models of organs for surgeons and by the Air Force for rocket engine parts. But until now, users may not have been aware of the security vulnerabilities inherent in the printing process.

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine (UCI) have shown that they can use a smartphone to record the acoustic signals coming from a 3-D printer’s nozzle and reverse-engineer the object being printed.

By capturing signals about the movement of the nozzle, the researchers were able to achieve almost a 90 percent accuracy rate when duplicating an object in their lab, which could present significant security risks. “Initially, we weren’t interested in the security angle, but we realized we were onto something, and we’re seeing interest from other departments at UCI and from various U.S. government agencies,” said Mohammad Al Faruque, director of UCI’s Advanced Integrated Cyber-Physical Systems Lab and research team leader.

“In many manufacturing plants, people who work on a shift basis don’t get monitored for their smartphones, for example,” he said. “If process and product information is stolen during the prototyping phases, companies stand to incur large financial losses.”

3-D printers use digital design plans to build up thin layers of material until an object takes form. Before printing occurs, the source code can be encrypted, but once the process starts, emissions produced by the printer create acoustic signals that contain information that can indicate the location of the nozzle.

In order to shield 3-D printers from eavesdroppers, Al Faruque believes engineers should think about ways to jam the acoustic signals, such as a white-noise device that will introduce random sounds.

Al Faruque and his team will present their findings at the International Conference on Cyber-Physical Systems in April.

NEXT STORY: Call for security science papers