Mandatory password changes -- not as secure as you think

Connecting state and local government leaders

Frequent, mandatory password changes are not only unnecessary but may in fact be harmful to security, according to studies on the subject.

Frequent, mandatory password changes are not just unnecessary. According to studies on the subject, they may in fact be harmful to security.

“Users who are required to change their passwords frequently select weaker passwords to begin with, and then change them in predictable ways that attackers can guess easily,” Lorrie Cranor, chief technologist at the Federal Trade Commission wrote in a recent blog post. “Unless there is reason to believe a password has been compromised or shared, requiring regular password changes may actually do more harm than good,” she said, adding that simply changing a password after a compromise will not be effective if related security issues are not addressed.

An earlier study out of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill supports this notion. The researchers studied the security of passwords belonging to over 7,700 accounts associated with former university students, faculty and staff who were required to change their passwords every three months.

“We believe our study casts doubt on the utility of forced password expiration,” said the authors said. “Even our relatively modest study suggests that at least 41 percent of passwords can be broken offline from previous passwords for the same accounts in a matter of seconds, and five online password guesses in expectation suffices to break 17 percent of accounts.” The researchers went on to say they found the survey’s results “alarming, albeit not surprising.”

The big problem? Users tend to generate fresh passwords based on old passwords, allowing attackers who know a user’s previous password to easily guess the new password. While not part of the study, the researchers hypothesized that “the increased mental effort required to choose a good password discourages these users from investing that effort again to generate a completely new password after expiration.”

Instead, the authors suggest requiring users to create significantly stronger passwords, and IT managers should consider alternatives to passwords, such as biometric security.

Likewise, Sonia Chiasson and Paul C. van Oorschot of Carleton University quantified the security advantage of password expiration policies in a report and found similar results. Mandatory password changes only moderately hinder a specific type of attack -- from attackers who know a user’s password.

“However, it provides little help against numerous other attacks, including those which upon first access immediately procure target files, set up a back door, or install keystroke-logging software or other persistent malware to render ineffective subsequent password changes,” the authors noted. Thus, “the security benefit of password-aging policies are at best partial and minor,” they concluded.

Based on mounting evidence against forcing users to change passwords, “the burden appears to shift to those who continue to support password aging policies, to explain why, and in which specific circumstances, a substantiating benefit is evident,” they wrote.

Cranor suggested that system administrators can adopt password hashing functions, such as bcrypt, to make it significantly harder for attackers to guess passwords without inconveniencing users.

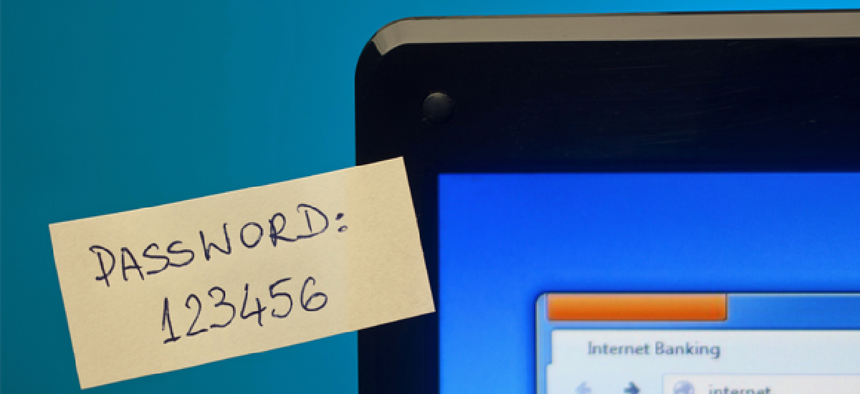

“There is also evidence from interview and survey studies to suggest that users who know they will have to change their password do not choose strong passwords to begin with and are more likely to write their passwords down,” Cranor said. “In a study I worked on with colleagues and students at Carnegie Mellon University, we found that CMU students, faculty and staff who reported annoyance with the CMU password policy ended up choosing weaker passwords than those who did not report annoyance.”

Organizations are beginning to take notice. The British government issued guidelines last year encouraging its systems administrators to simplify their approach to passwords, eliminate regular interval password changes and use automated controls to defend against automated guessing attacks rather than relying on users to generate and remember complex passwords.

“Encouraging users to make the effort to create a strong password that they will be able to use for a long time may be a better approach for many organizations, especially when combined with slow hash functions, well-chosen salt, limiting login attempts and password length and complexity requirements,” Cranor said. “And the best choice -- particularly if your enterprise maintains sensitive data -- may be to implement multifactor authentication.”