Virginia pilots mobile driver’s license

Tests of digital driver’s licenses show the potential of the technology, the leader of Virginia’s pilot program says.

The leap to mobile devices will be just the latest iteration in decades’ worth or changes to driver’s licenses, according to Raymond Martinez, the chief administrator for New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission. Licenses have moved from paper to plastic, added photos and now incorporate advanced anti-counterfeiting features.

But the hard copy has limitations, Martinez said at the May 2 Connect ID conference. Most notably, physical cards can’t be changed without drivers going to the Department of Motor Vehicles, making lines longer and creating more work for DMV staff. But if the identification was digital, those changes could be managed electronically.

The work toward making this a reality is already underway. Iowa was one of the first states to delve into the mobile identification landscape with testing that took off in 2015. Louisiana passed legislation last year that introduced the possibility of a digital ID, though it couldn’t be used to buy alcohol, tobacco or lottery tickets.

Dave Burhop, the deputy commissioner and CIO at the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles, spoke about his state’s work toward a mobile driver’s license.

In a three-month pilot, Richmond-area citizens who had a DMV Now account could download the mobile driver’s license application and use it for age verification at the locations that participated in the pilot, which included some convenience stores, local breweries and other locations.

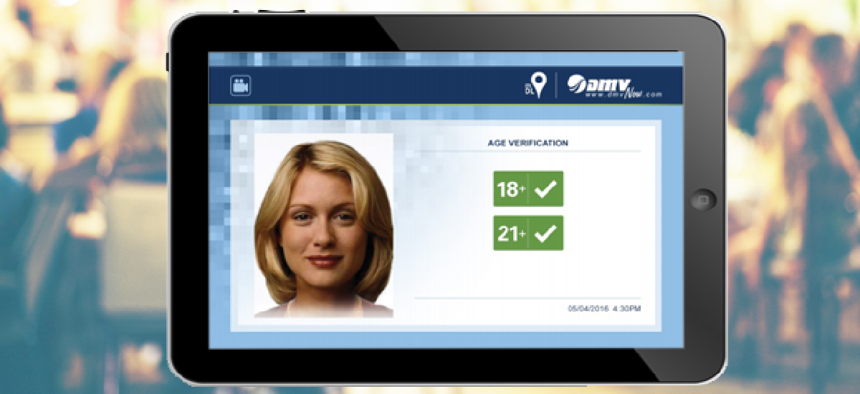

The Virginia digital license app issued a QR code that changed every time the user opened the app. A bartender or cashier scanned the user’s code with a tablet computer running a special application used to verify the mobile license, which sent an encrypted “token” to an intermediary -- Canada Bank Note Secure Technologies -- which in turn obtained the customer’s information from DMV via a secure web connection.

Once received, the CBN server used the information in the driving record to construct and send back a profile to the retailer that included a picture of the driver, an indicator as to whether the driver was over the age of 18, a separate indicator as to whether the driver was over the age of 21, and a date and time stamp. No customer birth dates were shared.

“The pilot provided some valuable lessons,” Burhop said, including the need to change a state law that was pointed out by the attorney general.

“The AG said it was the same as sharing data,” Burhop told GCN.

This year, the Virginia General Assembly passed SB1085, which gave the DMV the ability to “digitally verify the authenticity and validity of driver's licenses.” The bill was signed into law by Gov. Terry McAuliffe in March.

The pilot program didn’t just look at verifying ID for age-restricted transactions; it also examined how mobile licenses could be used in law enforcement situations. Both state and local law enforcement told Burhop and his team that they wanted a hands-free application; they didn’t want to have to invest in new hardware or have to carry anything up to a car on a traffic stop.

One solution they landed on was giving the users the ability to push their ID onto a server that could be accessed by law enforcement, along with that individual’s GPS coordinates. Then, the officers who need to see the ID could go to that server and look for licenses within 30 feet of their location. “It worked really, really well,” Burhop said.