Why confidence matters in facial recognition systems

Concerns over the accuracy of facial recognition systems came under the spotlight when Amazon’s Rekognition incorrectly matched 28 members of Congress to criminal mugshots.

If facial recognition is now a mainstream technology, then Apple’s November 2017 release of Face ID can be viewed as the turning point, according to a report from Forrester.

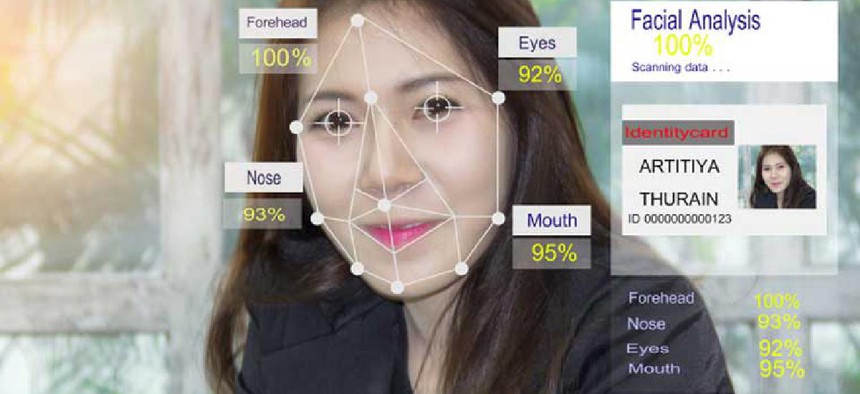

Facial recognition, a technology powered by machine learning, can now match users to faces in social media photos and help police find a criminal suspect.

But there have been concerns with the technology. Joy Buolamwini, a researcher at the MIT Media Lab, found it is less accurate for people with darker skin tones. It doesn't work well in low light or with images taken by thermal cameras used by the military. And even though more than 117 million American adults have their photos in law enforcement facial recognition databases, "most law enforcement agencies do little to ensure their systems are accurate,” a 2016 Georgetown University study found.

Concerns over the accuracy of facial recognition systems resurfaced recently when the ACLU released the results of a study that found Amazon’s version of the technology, Rekognition, misidentified 28 members of Congress.

“Using Rekognition, we built a face database and search tool using 25,000 publicly available arrest photos,” the ACLU said in the release of its findings. “Then we searched that database against public photos of every current member of the House and Senate. We used the default match settings that Amazon sets for Rekognition.”

Nasir Memon, a professor of computer science at the New York University Tandon School of Engineering, said it isn’t realistic to expect these systems to be completely accurate.

“False positives are inevitable,” Memon said. “After all, these are pattern recognition systems that do an approximate match.”

The “default match settings” has been at the heart of the conversation since the ACLU released its findings. Amazon and one researcher interviewed by GCN said the ACLU would likely have had fewer, if any, false positives had the confidence threshold settings been different.

The higher the confidence threshold, the fewer false positives and more false negatives. The lower the confidence threshold, the more false positives and fewer false negatives. It's a trade-off, according to Patrick Grother, a computer scientist at the National Institute for Standards and Technology who administers the agency's Face Recognition Vendor Test.

“It is always incumbent on any end user of a technology in any application to set the threshold appropriately,” he explained. “In this case, I don’t think Amazon or anybody else would claim that the threshold was set appropriately.”

This is exactly the point made by Amazon after the ACLU made its findings public. The default setting -- an 80 percent confidence threshold -- has its uses, but checking photos of members of Congress against a criminal database isn’t one of them, the company said.

“While 80% confidence is an acceptable threshold for photos of hot dogs, chairs, animals, or other social media use cases, it wouldn’t be appropriate for identifying individuals with a reasonable level of certainty,” an Amazon Web Services spokesperson wrote in an email. “When using facial recognition for law enforcement activities, we guide customers to set a threshold of at least 95% or higher.”

AWS General Manager of Deep Learning and Artificial Intelligence Matt Wood, posted a blog saying that law enforcement applications of Rekognition should use a confidence threshold of 99 percent. Amazon also reran the test conducted by the ACLU on a larger dataset and saw that the “misidentification rate dropped to zero despite the fact that we are comparing against a larger corpus of faces (30x larger than the ACLU test),” Wood wrote. “This illustrates how important it is for those using the technology for public safety issues to pick appropriate confidence levels, so they have few (if any) false positives.”

The ACLU did not respond to multiple questions including whether it planned to retest the software using a higher confidence threshold and focusing on false negative rates.

Higher confidence levels are, however, a double-edged sword because they will introduce more false negatives, meaning the system will fail to match or identify people it should be spotting.

“When you raise this confidence to a higher level, 95 to 99 percent, then you start getting more false negatives,” Memon said.

Grother said lower confidence thresholds can actually be used in law enforcement settings as long as staff can verify the results produced by the algorithm. He pointed to the investigation of recent shooting at the Capital Gazette newspaper in Annapolis, Md. The suspect wouldn't tell investigators his name, so officials ran his photo against the state's facial recognition database, which quickly returned a match.

“In that case you can afford to set a threshold pretty much of zero and what will come back from the system is a list of possible candidates sorted in order,” he said. “At that point you would involve a number of investigators to look at those candidates and say, ‘Is it the right guy or not?’ or ‘Is it the right person or not?’ because you have time," to sift through the possible false positives, Grother explained. "The opposite situation, when you want to run a high threshold, is when you’ve got such an enormous volume of searches or so little labor to adjudicate the result of those searches that you must insist on having a high threshold” that would produce fewer false positives.

The increase in the number of false negatives associated with a high confidence level also means it's easier for a malicious actor to trick the facial recognition system, Memon said.

“A malicious actor can actually take advantage of the fact that the threshold is very high and potentially try to defeat the system by simply changing their appearance a little bit,” he said. “There has been work that has shown that by just wearing [a certain] kind of shades, you might fool the system completely.”

Forrester’s report on facial recognition technology from earlier this year called the false positive rate “more critical to assess” than the false negative rate because the potential consequences of misidentifying someone can outweigh the risks of not identifying someone. Both measures should be considered when buying a solution, the market research firm advised.

“Seek to implement [facial recognition] solutions that operate in production at a stringent [false positive rate] of no more than 0.002% (one in 50,000) and a [false negative rate] of no more than 5%, but with the ability to make the [false acceptance rate] more stringent and the [false rejection rate] higher if the firm’s needs change,” Forrester suggested.

Rekognition is currently being used by the Sheriff’s Department in Washington County, Ore. Another locality that was testing the technology, Orlando, Fla., decided in June not to move forward after piloting it, but in July said it would continue with its testing.

Perhaps the most visible use of facial recognition technology has been efforts by the Transportation Security Administration and Customs and Border Protection, which are testing systems at Los Angeles International Airport. and other major airports to verify identities of international passengers. TSA told GCN that facial recognition “is still in the development and testing phase.”

Before making it into the airport for the pilot phase, the technology “undergoes a thorough and rigorous testing and evaluation process in a laboratory setting,” Michael McCarthy, a spokesperson for the TSA, said in an email. “The information gathered during pilot tests helps determine whether a technology may move forward in the testing process or whether it requires additional development and testing in a laboratory environment,” he said.

The availability of the Rekognition facial recognition technology through the AWS cloud could speed widespread adoption, in spite of its relative immaturity and standards that change depending on the use case, Grother said.

But given the easy access, Memon said, it could be time to start looking at some kind of regulation.

NEXT STORY: Bridging federal IT’s knowledge gap