Gamification isn't about games, but the players

Connecting state and local government leaders

As agencies move toward greater use of gaming, an industry leader points out that the key element is not graphics or simulations, but motivation.

Video game designers have been saying it for years: Games can develop and sharpen skills that players can use in real life. And they aren't just talking about military training games.

IBM released a report in May titled "Fast Government," that points to a broader acceptance of the idea of gamification and to broader application of gamification principles. In the report, Nicole Lazzaro, president of XEODesign, writes that, "If crafted appropriately, applying the lessons from the thinking used in designing games could have the potential to transform how government communicates, provides information and delivers public services."

This is not exactly breaking news for some in government. Indeed, the General Services Administration's HowTo.Gov site offers a webinar on the subject, as well as an analysis of gamification's potential in federal projects. And many agencies are already applying gamification.

But many of those leading the way plead with listeners not to confuse gamification with games. "It's not about simulation. It's not about training games. It's not about 3-D graphics," said Rajat Paharia, founder and chief product officer of gamification company Bunchball.

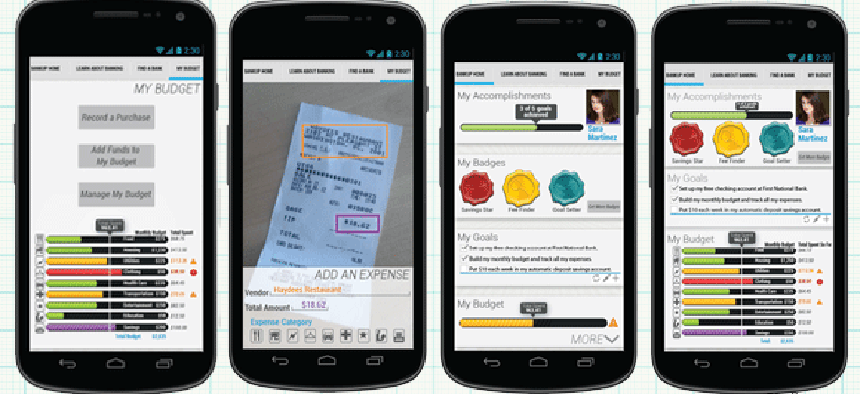

"When we talk about gamification we're talking about motivating people through data. Game designers have learned how to motivate people by giving them goals to accomplish, by giving them really fast feedback, by letting them see their statistics, by giving them badges for hitting milestones. What gamification is -- is taking those game-driven motivational techniques out of games and using them elsewhere."

Paharia cites the example of Hope Lab, a non-profit organization in Redwood City, Calif., that is fighting teen health problems. Hope Lab created Zamzee, a device that looks like a USB flash drive but is actually an activity monitor that kids wear on their belts and to monitor their physical activity, Paharia said. At the end of the day, they plug the device into a USB port and it uploads all of their activity data.

"For every 10 minutes they spend at a certain exertion level they get a point," he said "They can track their progress over time. And they have missions to accomplish. For example, 30 minutes of a certain activity will unlock a badge."

And it’s gotten results. "They've been able to show a 59 percent increase in activity among those kids,” Paharia said. “They've shown drops in bad cholesterol and blood sugar levels. Government can use these kinds of things to affect the health of the populace."

Bunchball is just entering the government sphere, but Paharia said the company is seeing growing interest in gamification technologies on the part of agencies. "Government is trying to figure out how to engage everybody," he said.