GIS becomes indispensable for managing agriculture

Connecting state and local government leaders

USDA is combining satellite images and streams of agricultural data into interactive maps anyone can use.

To hear analysts at the Agriculture Department talk, geospatial information systems are moving from being merely useful tools to becoming game changers.

Thanks to a perfect storm of rapidly enhanced sensor technologies, more powerful computers and improvements in GIS applications themselves, GIS is becoming the platform of choice for combining and analyzing huge streams of data. And the ability to analyze those data streams and display results visually on maps has engendered a number of new projects and capabilities that have users clamoring for more.

"The use of GIS has become recognized as really a core administrative function of the department," said Stephen Lowe, director of the Enterprise Geospatial Management Office at USDA. "That's a significant shift."

The ability of applications such as Esri ArcGIS, the primary GIS program used at USDA, to handle growing streams of data — from satellite imagery to old-fashioned tabular data — and then to display the data in a visual geographic fashion, make them ideal portals for coordinating many kinds of department operations.

In the event of, say, a major flood, government will have many concerns, Lowe said. "We'd be looking at the whole economic base, obviously, for an area. How does that affect municipal services? How does that impact our policy and programming decisions? I think you're getting a much richer set of insights into these kinds of events by having a single platform based on a geographic area."

By tying together all of the different sets of background data through a GIS application, teams can gain unprecedented power. "You have the ability to do diagnosis of problems," Lowe said. "You have the ability to classify problems, do interpretation analysis and prediction, forensics — all of these things that people haven't really thought about in terms of mapping. We're discovering the analytic capacity of these tools for bringing different disciplines together to solve problems more efficiently.

“It's a much more collective kind of future that I see for us, and there is an appetite for it."

At the same time as GIS is allowing for more effective data analysis by specialists within an organization, new GIS tools are also increasingly effective as a means of reaching out to deliver content to non-specialists. "How do we create the means for people who are out in the field, who are not GIS-confident necessarily ... to tell a story geographically?" Lowe said. "We don't want to just rely on the specialist. We want to extend the power of mapping to anyone who wants it." USDA is increasingly porting subsets of its data to Web applications using such tools as ArcGIS Online.

Cropping out fraud

One of the more dramatic examples of the effectiveness of GIS technologies at USDA is its Risk Management Agency's program to set crop insurance rates and to detect fraudulent claims of crop losses.

The Insurance Services unit's regional offices produce FCI-33 rate maps in Esri ArcView. "They identify areas where there may be something that could impact the production of a crop," said James Hipple, remote sensing and GIS adviser for RMA. "It could be an area that is prone to flooding … it could be an area where the slope or aspect leads toward a potential risk for that crop that is different than the risks and the rest of the county."

The FCI-33 rate maps draw upon data from a variety of sources, including soil data from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, floodplain data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, farm location and crop data from the Farm Services Agency, historic weather data and satellite imagery. After assessing all this data, the agency analyst will create rate zones in the FCI-33 maps. "If a producer is within this zone they get a different-than-standard-rate insurance offer and if they are outside of this zone they get the standard offer for that particular crop," Hipple said.

Once the maps are created, they are integrated into the RMA production environment, where insurance providers can access them. And RMA has also ported the maps to a Web service so that farmers can check them. If the farmer has issues with the zone classification he receives, he can submit a request for a rate change.

"With all of the geospatial data that’s come in, we're able to really, really refine these maps," said Hipple. "If there is a flood that occurs, our lines are really accurate in terms of being able to determine areas that flood versus those that don't. Going back 20 years, it was just an eyeball in a couple of pencils."

The GIS capabilities are, in fact, so good that the RMA also uses them it to catch those making fraudulent claims of crop losses. Using data from the recently launched Landsat 8 satellite, the RMA is able to determine whether damage to crops after a flood or other weather event has actually occurred.

"I've been working in this arena since the early 1990s," Hipple said, "and many of the things that have been promised in GIS are actually really now starting to come to fruition."

CropScape and VegScape

USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service has also recently turned to GIS Web services to make its huge Cropland Data Layer (CDL) easier to access for the public.

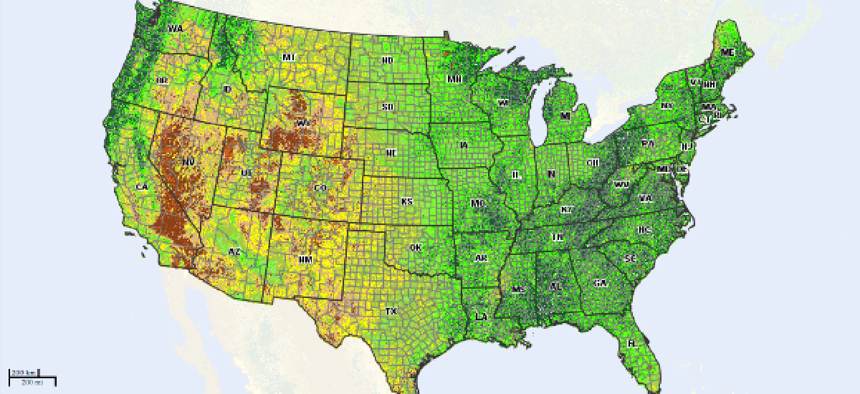

The CDL contains geocoded satellite imagery of crop acreage that NASS analyzes in order to produce crop estimates.

"Basically we map all of the crops for each crop year," said Jeffrey Bailey, chief of NASS' Geospatial Information Branch. "We map over 100 different crops and we use that also to make official estimates during the growing season." The maps have been produced since 2008 and each year's data is publicly available through 2012.

NASS has had access to Landsat imagery since 2006 and since 2011 the service has received imagery from the Disaster Monitoring Constellation satellites. That imagery is integrated with ground data from the Farm Service Agency.

"From our ground data, we know that a specific pixel is a cornfield," explained Bailey, "and we look at its spectral signature. We get about two images a month, so we can see the green up of the crop."

In short, NASS analysts are able to determine not only what crops are on each piece of land, down to a resolution of 30 meters, but the degree of growth between images.

The satellite data by itself isn't yet up to task. "We need the ground data to get accurate results," Bailey said. But with the ground data added, he says, the accuracy of the application is in the mid-90's percentile.

Each year's imagery data alone now amounts to approximately 10 terabytes, and Bailey's team now has approximately 40 T of data. And while all that data is accessible to the public, it would not be feasible for most users to download the entire data set.

Accordingly, NASS has produced an online application that provides not only access to selected data, but built-in query and reporting tools. "The CropScape website provides an efficient way to distribute the data and eliminates the need to distribute DVDs via snail mail or FTP," Bailey said. "More importantly it enables more people who do not have GIS software to interact with the data right on the website."

The web application, which was launched in January 2011 has, he said, been a hit. "CropScape has empowered the masses to perform area change and rotational crop analysis with a queryable, interactive interface," he said. The masses he's talking about, he adds, are primarily academic researchers. "CDL end-users are now documenting their uses in peer-reviewed literature, with uses of the CDL product ranging from research on agricultural sustainability studies, environmental issues, land conversion assessments, crop rotations, decision support, disasters, farmer surveys, carbon, bioenergy, ecology and biodiversity."

CropScape was so popular, NASS followed it up with VegScape, another Web GIS application that was launched in February 2013. VegScape provides weekly maps that display the crop conditions based on infrared data from NASA's MODIS satellite. The health of crops can be assessed by measuring the amount of infrared light they reflect.

"It's amazing," Bailey said of the response to the new GIS tools. "Usage of the data is been quite extensive. People are looking at rotational analysis. People are looking at stability studies, environmental issues, conservation assessments, decision support for disasters, farmer support."

Cross-breeding data

Given that USDA's mission is very geographically oriented — from monitoring the health of croplands to managing the national forests — it's no surprise that dozens of GIS applications have been developed over the years by many of the department's 17 agencies. And as GIS software has grown to manage large data streams and offer more powerful analytic tools — combined with more accurate sensor data from a variety of platforms — the capabilities have blossomed.

But the new, more powerful role for GIS is as a platform for tying together databases from many sources, for leveraging efforts across the department's agencies.

"It's a container for all of these really creative ways of re-conceiving and redefining problems in ways that are more relevant and valid for those in a particular area," Lowe said.

Noting that individual agencies in the department have long had a high level of operational expertise, and that there was increasing standardization of formats and software, Lowe said the department recently realized that there was an opportunity to better connect the data through the GIS platform.

"They were not thinking enterprise," he said of the individual agencies. "They were not thinking about when a GIS practitioner creates a map on his desktop: Is he creating it to solve the immediate problem or is he thinking this might actually be applied to something else, and extend the lifecycle of that product in a way that really makes it more useful, that makes it more accessible to other people?"

Lowe points to Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food as the department's first Web GIS application at the enterprise level. Fully deployed in the cloud, it offers information from over two dozen different USDA programs across the nation as well as nine other federal agencies.