Solving art history mysteries with open data

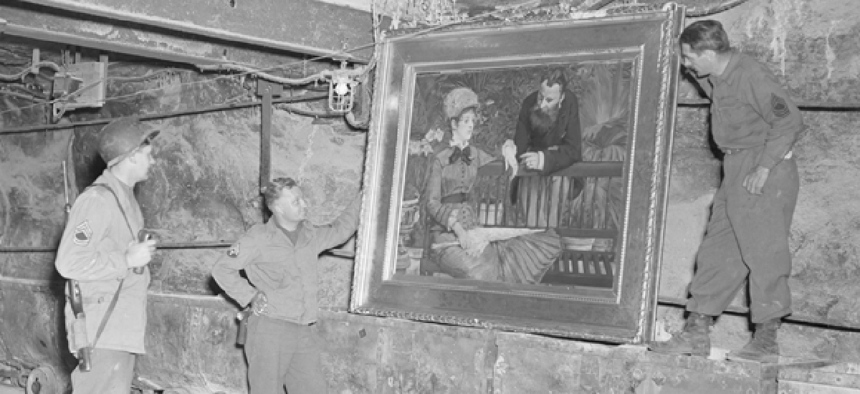

Making provenance data open and accessible gives more people information about a piece’s sometimes sordid history, including clues that might uncover evidence of Nazi confiscation.

With programs like the Carnegie Museum of Art’s (CMOA) Art Tracks at some of the world’s most famous museums, more people have access to information about a piece’s sometimes-sordid history -- including clues that might uncover evidence of Nazi confiscation.

Provenance generally was consider to be the information tucked in the back of a catalog that was relevant only to a tiny pool of scholars and experts, said Tracey Berg-Fulton, collections database associate at CMOA. “Because we’re now being more explicit about the mechanisms behind how art transfers from person to person and travels from place to place, we’re discovering fascinating connections between people, history and objects.”

And could a more-defined history affect art ownership? Possibly, said Berg-Fulton. “The tools we’ve designed have a timeline that really illustrates periods of ambiguity and uncertainty, and so that can help point out a period of possible Nazi confiscation.”

On a larger scale, Berg-Fulton said, making provenance more accessible will also help institutions resolve the ambiguity involved in ascertaining possible Nazi provenance. “I think the most likely impact will be that institutions either a) identify more works that should be listed on their lists of works with possible Nazi provenance or b) it will help them clarify and conduct better research on their works with possible Nazi provenance.” She also said the amount of archival information about Nazi appropriation coming online is steadily increasing, and so the effort to identify pieces with Nazi provenance will only improve.

The CMOA is also moving beyond Art Tracks’ scope to track Nazi ownership with a new grant -- funded by the Kress Foundation -- to create software specifically designed to identify Nazi provenance. “Many museums did this manually in the early 2000s in order to generate a list to post on the Nazi Era Provenance Internet Portal, said Berg-Fulton. “That process was a very manual and time-consuming one, and so we’re exploring ways in which we can use software and the existing data to point out works with possible Nazi provenance using the parameters set out by the American Alliance of Museums.”

Ultimately, Berg-Fulton just wants to find ways to move the research into the digital age so that a piece’s history isn’t so mysterious and it can be returned to its rightful owners. “My hope is that the increased availability of archival information in digital format lowers the barrier for not only institutions researching works in their collection, but heirs and claimants researching works that were stolen,” Berg-Fulton said.

NEXT STORY: Open data dusts off the art world