Putting Digital Equity in Cities Front and Center

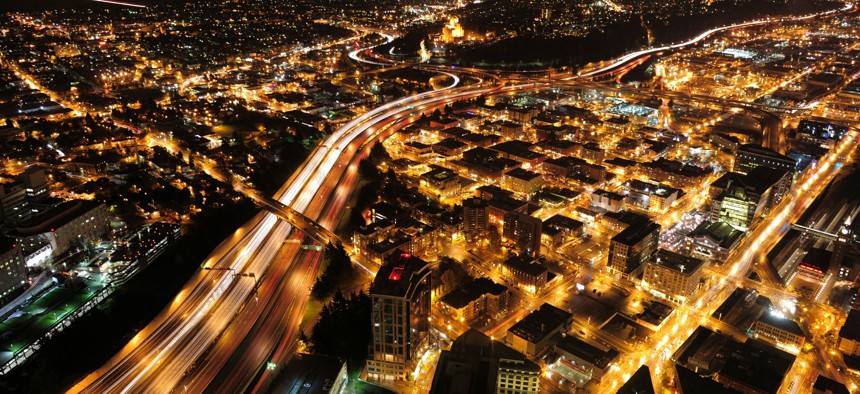

Looking southeast from downtown Seattle. Estar / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

There are plenty of opportunities and challenges for municipal leaders who want to expand access to high-speed Internet in their communities.

WASHINGTON — Providing Wi-Fi hotspot devices that can be checked out from libraries, connecting residents in public housing with high speed Google Fiber service and beaming down wireless Internet signals to rural areas using balloons. These were among the emerging approaches to improving digital equity that came up during a panel discussion here on Tuesday.

The discussion was held as part of the National League of Cities 2016 Congressional City Conference, and focused largely on how to improve high-speed Internet access and digital literacy among low income communities and other underserved groups.

Panelists included Google’s director of state policy, John Burchett, who is involved in the company’s gigabit fiber program; Seattle’s chief technology officer, Michael Mattmiller; and Gwenn Weaver, a senior communications program specialist with the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

Mattmiller at one point referred to the recent findings of a committee advising Seattle policymakers on digital equity issues. His comments aptly framed Tuesday's discussion. “They said that technology is for everyone,” he remarked. “And that in a city like Seattle and a country like ours today, where information is critical to success, there needs to be digital equity for all.”

But the obstacles some communities face on this front were underscored when a Common Council member from Gary, Indiana, spoke up during a question and answer segment.

“We’re really in a bad way,” said Rebecca L. Wyatt, who represents the city’s first district. She said a problem in Gary is that many people cannot afford Internet service, and do not have devices to get online with anyway. “Plus,” she added, “our libraries are closing.”

“I just wanted to emphasize how important it is to think of those really poor communities,” Wyatt said. “And how far behind they will be, if we don’t pay attention to the expensive accessibility and to the hardware.”

‘It Doesn’t Take a Lot of Money’

Last year, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray’s administration deemed the idea of building out a high-speed municipal broadband network too expensive for the city to take on without a private partner, or a significant new source of funding. Estimates in a report the city commissioned ballparked the cost between $460 million and $630 million.

Making up for that level of investment, Mattmiller said, would mean charging monthly user fees around $75 per month, and that about 43 percent of Seattle households would need to subscribe to the service in order for the city to break even.

“When we studied what it would take to be successful,” he said, “we realized it was just not within our financial capacity as a city.”

But Mattmiller described other advances Seattle is making to expand online access. Last year, Microsoft announced a partnership with the city to provide free wireless Internet in the city’s Lower Queen Anne neighborhood. Google, meanwhile, offered up a grant that went toward purchasing 250 wireless hotspot devices that can be checked out at city libraries.

“We saw such tremendous success,” Mattmiller said, “as part of the mayor’s budget for 2016 we purchased 500 more devices.”

He also noted Seattle’s Technology Matching Fund program. In 2015, the city awarded nearly $500,000 through this program to about 30 community organizations that had ideas for bridging digital divides. Examples of what the grants have gone toward include community-center-based efforts to prepare students for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, or STEM, education, and creating a computer lab for senior citizens.

“It doesn’t take a lot of money to have a very significant impact,” Mattmiller said.

Additionally, he added, the city has attempted to push Comcast to broaden less expensive Internet service offerings for groups like seniors, and veterans. The aim is to get groups such as these signed up for service that costs about $10 per month.

‘We Aren’t Going Just to the Wealthy Neighborhoods’

Google Fiber is now operating in Atlanta; Austin, Texas; Provo, Utah; Kansas City, Kansas; and Kansas City, Missouri. Roll-outs are under construction or consideration in other cities as well.

Billed as a gigabit-speed television and Internet service, Google Fiber offers uploads and downloads at speeds up to 1,000 megabits per second. Burchett pointed out that the average American now has access to Internet speeds around 11 megabits per second.

“It’s dramatically faster,” he said of Google’s service.

But it is slow-going getting the fiber networks up and running.

“We’ve been experimenting and playing around for a couple years,” Burchett said. “It takes a long time to construct these projects.”

Digital inclusion, he emphasized, is a key part of the company’s fiber enterprise. “We aren’t going just to the wealthy neighborhood where we’re going to make the most money immediately,” he said. “We’re making sure we’re hitting digitally divided neighborhoods as well.”

In early February, the West Bluff Townhomes in Kansas City, Missouri, became the first public housing complex to be connected to Google’s gigabit service. The service was offered to 100 housing units there free of cost, through a federally-backed public-private collaboration known as ConnectHome. At the time of the announcement, service was slated to become available to another 1,300 public housing units in the Kansas City metro area.

“We aren’t going to be able to do this everywhere,” Burchett cautioned.

Going forward, he said the company would be targeting its low-income service offerings toward census tracts that appear to be the most digitally divided.

Establishing fiber connections alone, however, can fall short when it comes to bridging equity gaps. Burchett and the other panelists stressed that digital literacy efforts are crucial.

To help address this area, Google has launched a digital inclusion fellowship program. Fellows will be embedded with partner organizations in towns where Google Fiber is being put into place, and charged with promoting digital literacy, such as basic computer and Internet skills.

For those cities looking to get on the list for a Google Fiber build-out, it may be a while.

“We are growing and are really having a hard time even moving forward quickly with the cities that we’re already engaged with,” Burchett said. “So we aren’t taking applications.”

That said, to better prepare for the eventual arrival of gigabit-speed Internet service there are steps that cities can take, which Burchett said are outlined in a checklist Google has posted online. Some of these preparations pertain to somewhat dull-sounding topics, he warned. For instance: clarifying rules governing the attachment of fiber to utility poles.

Burchett had another recommendation as well. “When you’re doing construction now,” he said, "lay fiber, and lay fiber conduit, every time you open up a street.”

‘Answer Will Not Be Wires for Rural America’

When it comes to providing equitable access to the Internet, rural areas present unique challenges. In sparsely populated places, where there are long distances between homes, it can be especially tough to economically provide wired broadband services.

“Rural America is one of the biggest areas of concern,” the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s Weaver said.

But there are new technologies emerging that show promise for getting outlying areas connected.

Burchett said a Google subsidiary, now known as “X,” is doing a variety of research in this area.

One of the X undertakings is dubbed Project Loon. It would rely on balloons floating in the stratosphere, and sending down wireless signals that can be used to access the Internet. So far the technology has been tested in California, Brazil and New Zealand.

Another possibility X is experimenting with is transmitting Internet signals down to the earth using solar-powered planes.

“From everything I hear internally,” Burchett said, “the answer will not be wires for rural America.”

Measuring Success

All of the panelists acknowledged that measuring the effectiveness of digital equity initiatives can be difficult, and that determining the best metrics to use is a work in progress.

“I’m not sure that there’s a gold standard,” Burchett said, referring to metrics.

Weaver agreed. “There is no single way that this is being done right now,” she said of measuring how well digital inclusiveness efforts are performing. Weaver did note that research is taking place at the federal level in this area.

“You have lots of anecdotal evidence,” she said. As an example, Weaver pointed to letters from people who had said digital literacy training had been a stepping stone toward getting a job.

“They’re heartwarming,” she added, “but they aren’t the hard evidence that we need.”

Bill Lucia is a Reporter for Government Executive’s Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Ransomware Attacks Continue to Stack Up and Local Agencies Remain at High Risk