NOAA, NASA support flood response with data

Connecting state and local government leaders

As satellite data and computing power increase, research agencies like NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are supporting disaster response operations with real-time data and analysis.

A government response to a flood typically involves operational assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the National Guard. But as data streams become faster and more efficient, research agencies like NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are also supporting those operations – with real-time data and analysis.

NOAA has developed a national water model that delivers three different reports on the state of water flow and soil saturation. The data is released in three channels in regular intervals throughout the day and provides the most comprehensive look at the nation’s creeks, streams and rivers that has ever existed. NASA, meanwhile, has created a rapid-response team that provides data and analysis to organizations like FEMA; it has responded with satellite mapping of the Nepalese earthquake and data on rainfall for the recent deadly flooding in Louisiana.

Dalia Kirschbaum, a disaster response coordinator for NASA, said the rapid response team has only been in existence for about a year, and it is still trying to determine its role in disasters such as the one unfolding in Louisiana. This means talking to FEMA every day during an event that both organizations are responding to; these conversations give responders a better understanding of the data and products that NASA can provide.

Much of what NASA offers during a flooding event is inundation data: How much rain fell? Where did it fall? It’s important, though, to provide this information in an accessible format, Kirschbaum said, which can mean combining the data with geospatial information or other models to increase the “usability of the data” so it can be quickly applied in the field.

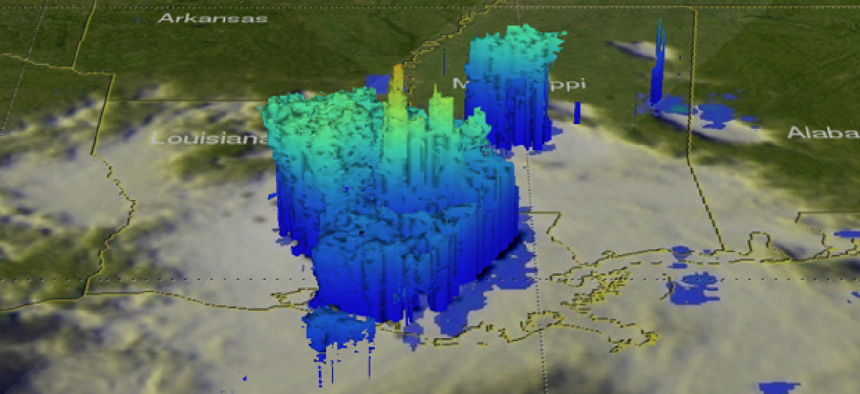

Some of the data that NASA provides is coming from the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) satellite, which estimated that more than 27 inches of water fell in the week of Aug. 8 from the storm in Louisiana. The satellite can collect data through cloud cover, layer by layer, every 250 meters, to measure the amount of moisture in clouds, droplet size and other data, according to Gail Jackson, a NASA GPM scientist.

Jackson said the satellite’s two-frequencies allow it to detect different droplet sizes. An earlier NASA satellite that measured precipitation in the tropics only used one frequency to pick up the large, tropical droplets. But GPM can see much smaller types of precipitation. Jackson said her team would like to add a third frequency to give it data on an even larger area -- from the Arctic Circle to the Antarctic Circle.

The GPM satellite sends the information to a constellation of smaller satellites outfitted with high-gain antennas, which then downlinks the data to a terrestrial station at White Sands, N.M., and then to NASA’s Goddard facility in Maryland.

NOAA’s new national flood model can provide some data similar to what NASA’s GPM provides, such as day-of inundation info, but it can also create forecasting models by combining multiple datasets.

Brian Cosgrove, the project lead for the water model, said that NOAA’s Office of Water Prediction realized it needed more sophisticated modeling. A year and a half later, NOAA’s Cray XC40 supercomputer is crunching the data to create a “mathematical representation of the water cycle across the U.S. to produce analysis and forecasting.” It shows observed flow and forecasted flow by combining a number of different datasets like weather forecast models, precipitation information from radar and streamflow observations from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Aside from one interactive image viewer, the data is mostly raw. It is sent out over NOAA’s web-based National Operational Model Archive and Distribution System, placed on the Office of Water Prediction website and sent to 13 river forecasting center across the county to help refine forecasting.

Edward Clark, the director of the geo-intelligence division at Office of Water Prediction, said the team wants to integrate geospatial datasets like road networks, critical infrastructure and demographics, which will not only predict the water’s behavior, but also the magnitude an impact of potential flooding.

Meanwhile, lessons learned in Louisiana will help agencies respond better the next time a similar event happens. NASA will complete an after-action report and has compiled playbooks for different types of disasters, Kirschbaum said. “It’s an evolving process.”

NEXT STORY: A proving ground for smart city tech