Smart inhalers help monitor air pollution

The AIR Louisville program uses smart connected inhalers that track when, where and how often asthma patients use their devices.

Clean air advocates in Louisville, Ky., have an unusual partner in their efforts to influence local environmental policies on air quality and pollution -- the sensors on asthma inhalers.

Officials in the city, which frequently sits in the top 10 of the Asthma and Allergy Foundation’s Allergy Capitals lists, hope to use inhaler data in combination with weather and air quality data and demographic information from federal sources to inform policies that would reduce pollution.

The AIR Louisville program uses smart connected inhalers that track when, where and how often asthma patients use their inhalers. The information can not only help patients manage their symptoms, but it collects data about the location and severity of pollution based on inhaler use.

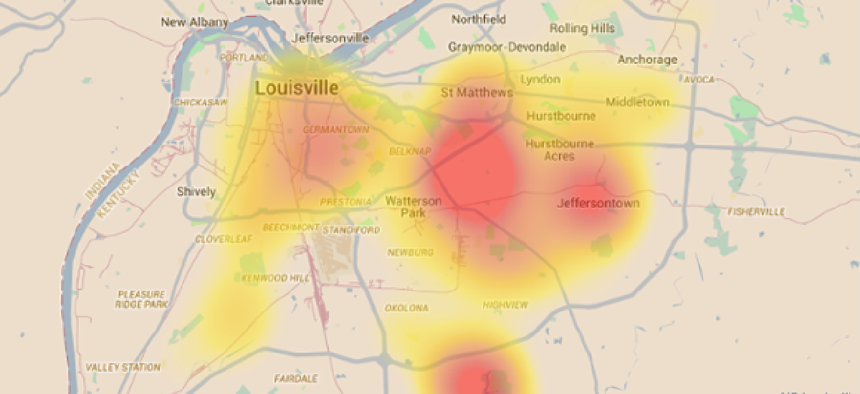

Louisville, part of Jefferson County, sits in the Ohio River Valley and the surrounding hills can trap pollution. “Our geography basically works against us,” said Veronica Combs, vice president for partners and programs at Louisville’s Institute for Healthy Air, Water and Soil. By using the smart inhalers to create heat maps of the county’s asthma hot spots, she hopes small changes can be made that will produce big results for the city’s health.

“Our goal is to take this back to the city and say, ‘Let’s look at these particular neighborhoods,’” Combs said. “We’re hoping to use this data to shift the conversation about air quality and health.”

When AIR Louisville registration closed at the end of September, more than 1,100 people had enrolled. Participants had to be at least 5 years old, diagnosed with asthma and live or work within Jefferson County. So far, AIR Louisville has collected 97,000 data points about asthma medication usage there.

Enrollees received sensors from Propeller Health, an AIR Louisville partner that developed a digital platform for respiratory health. One sensor was for rescue inhalers, used for acute asthma attacks, and another for any maintenance inhalers. Each time users depress the container, the sensor records the date and time and sends the information via Bluetooth to the Propeller app on the user’s mobile phone.

The data also goes to Propeller Health’s Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant servers along with location data from the phone’s global positioning system. Participants who don’t have smartphones transmit data through a wireless hub that plugs into an outlet in the home.

Propeller Health also collects pollutant data from 10 Environmental Protection Agency sensors around the city, weather data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, land cover data from the U.S. Geological Survey, traffic data from the Transportation Department’s Highway Performance Management System and neighborhood characteristics from the Census Bureau and its American Community Survey.

“We have an analytic engine running in the background that’s basically crunching all of those records and all of that rescue medication-use events that that person has had,” Propeller Health’s VP of Science and Research Meredith Barrett said. “We’re doing all of the calculations, looking at all the associations between where and when their symptoms happened and what the environmental conditions were at that time.”

Dashboards for users and health care managers display data on medication usage in ways that will help users understand their triggers and let care managers track asthma sufferers in distress. No dashboard is available for city managers, but Propeller and AIR Louisville make frequent reports, including heat maps that indicate where the greatest concentrations of asthma attacks are happening at any point in time. City policy makers can also see what the weather was like, how many pollutants were in the air and how much traffic was in the area during a peak attack time so that they can make more informed decisions about improvements to the city.

“Because we do have the geographic location of each asthma attack, we can see if there is a certain part of town that has a higher burden than others,” Combs said. “Maybe it’s the downtown business district because there’s more traffic and fewer trees, or maybe it’s a certain part of town with a lot of industry, or maybe it’s a school that’s near a really busy freeway.”

Solutions could be to plant more trees in those areas to pull more pollution out of the area and make it cooler or to recommend a no-idling policy near specified schools or businesses, for example.

“You can’t say, ‘Oh, it’s our technology that saved the day,’ but you can at least have some proof of raw numbers,” Combs said.

AIR Louisville began in 2012 with about 300 participants -- too few to produce enough data points to get meaningful information, according to Combs. In late 2014, a two-year grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation enabled the city to expand project to its current state.

Interest in smart inhalers is growing. Other companies, including AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Teva Pharmaceuticals are developing inhalers with sensors with partners such as Qualcomm and IBM Watson. Barrett said that Propeller Health is in talks with six or seven other cities about bringing this technology to them.

“This is a pretty unique program that really is able to use technology to leverage citizen science on the individual level,” Barrett said of AIR Louisville. It enables “residents to be able to collect data, but then it has an impact at a policy level.”

NEXT STORY: Progressive web apps: The mobile future?