State Officials Question Benefits of Federal Election Oversight

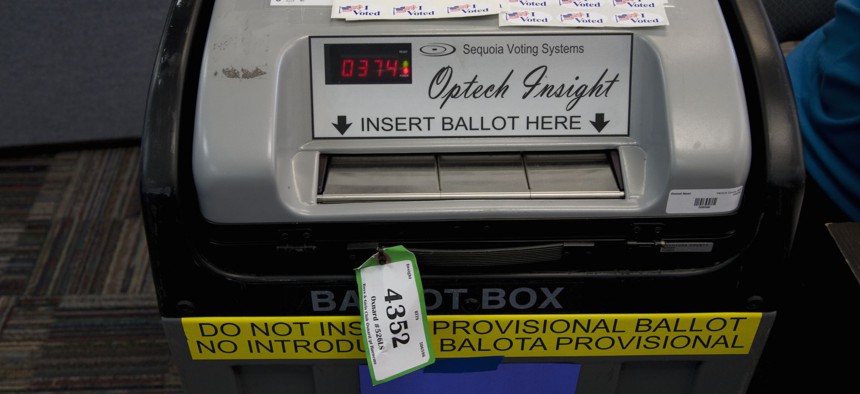

Shutterstock

DHS officials told a hearing of the Election Assistance Commission that aid is vital to prevent government-backed hackers from Russia and elsewhere from undermining the validity of election results or throwing an election into chaos.

Federal cybersecurity leaders Tuesday faced questioning that ranged from highly skeptical to outright hostile as they defended a decision to increase federal oversight of state and local election systems.

That decision, taken late in the Obama administration, to designate election systems as critical infrastructure is supposed to make it easier for the Homeland Security Department to vet election systems’ cybersecurity and to provide classified information about cyber threats to state and local election officials.

That aid is vital, DHS officials told a hearing of the Election Assistance Commission, to prevent government-backed hackers from Russia and elsewhere from undermining the validity of election results or throwing an election into chaos—perhaps by compromising the integrity of voter rolls or of the systems that report vote totals from different districts.

The designation also sends a signal to Russia and other nations that cyber meddling in U.S. elections, as Russian spy agencies did in 2016, will invite major U.S. retaliation.

The designation could also extend the federal government’s reach into state and local affairs, however, and raise the public perception of partisan influence in the nuts and bolts of election operations, state and local officials fretted.

The designation does not provide additional funding to states and localities to upgrade their election technology or other advantages, the officials said. Among its major advantages, DHS Enterprise Performance Management Office Director Neil Jenkins said, is it makes it easier for DHS to organize its own resources around sharing information with state and local entities.

The National Association of Secretaries of State—the state officials responsible for managing state and local elections— passed a resolution condemning the designation in February.

Those concerns contributed to a combative atmosphere during Tuesday’s hearing. At one point, Robert Hanson, a director in DHS’ Cyber and Infrastructure Analysis Office, joked he and Jenkins “forgot our Darth Vader helmets, which might have been apropos for this.”

“Critical infrastructure” is an official designation DHS applies to 16 industry sectors including transportation, energy plants and financial firms that coordinate with each other and with the federal government to ensure cyber and physical security against attacks from criminals, terrorists and adversary nation-states.

The designation isn’t appropriate for election systems, state and local officials said during Tuesday’s hearing, for two main reasons.

First, voting machines themselves are almost never connected to the internet, so there’s limited danger of a cyberattack targeting actual vote tallies. Systems that do touch the internet, such as voter registration databases or tabulating systems, vary greatly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, so it’s unlikely federal or even state officials will be more expert in them than the local officials who manage them.

Russia-linked hackers did breach election databases in Illinois and Arizona in 2016, but did not compromise sensitive information. The majority of the Russian influence operation to undermine the election involved hacking and then releasing information from Democratic political organizations and the Hillary Clinton campaign, which are not part of the critical infrastructure designation.

While the designation does not require election officials to accept any DHS aid or to follow DHS best practices, state and local officials are concerned those could become back end requirements, National Association of Secretaries of State President Denise Merrill testified.

For instance, if a state chooses to follow its own security guidance rather than DHS’ and then gets breached, that fact could be used against the state in litigation, said Merrill, who is secretary of state for Connecticut.

Second, the public perception that elections are vulnerable to attack can be almost as damaging to public trust as the reality of an attack, Merrill said.

If state and local officials are relying on classified cyber threat information they can’t share publicly, that could give fodder to critics who say they’re hiding critical information or secretly working on behalf of whichever political party holds the White House, Merrill and other officials said.

As if to bolster, Merrill’s point, EAC Commissioner Christy McCormick asked Jenkins, the DHS official, to list the 33 states and 36 localities DHS says accepted assistance in securing election infrastructure during 2016. Each time, he declined to answer, saying DHS does not share that information out of concerns about giving adversaries valuable targeting information.

“Right now, our system is designed to foster transparency and participation from end to end,” Merrill said, “from public testing of voting equipment to poll watchers to public counting of the ballots to post-election audits. If the critical infrastructure designation reduces diversity, autonomy and transparency in state and local election systems, the potential of adverse effects from perceived or real cyberattacks will likely be much greater and not the other way around.”

Joseph Marks is a Senior Correspondent for Nextgov, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: Fully digitized credentialing for health professionals