ODmap gives responders real-time overdose data

Connecting state and local government leaders

Geocoded information about overdoses is sent from responders' smartphones to a secure server where it can be analyzed by authorized personnel.

The Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (W/B HIDTA) is using data to tackle the opioid overdose emergency sweeping not just this region but the country.

The organization, one of 28 nationwide but the only one that also gets funding for drug treatment programs, built the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMap), a web-based tool that first responders and public health and safety chiefs can use to track spikes in fatal and nonfatal overdoses in real time.

“The only way we’re going to get to the heart of this overdose [crisis] is to leverage information technology and data sharing, and we need to connect public health and public safety, and that’s the whole point of ODMap,” said Jeff Beeson, deputy director of management coordination at W/B HIDTA, which serves D.C., Maryland, Virginia and parts of West Virginia. “We’re connecting public health and public safety through data, and we’re saving lives.”

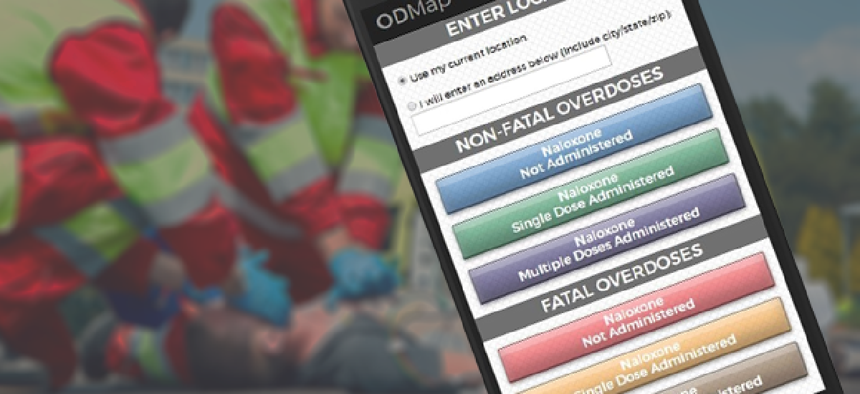

Level I users -- first responders from law enforcement, fire and emergency medical services -- open the tool on any mobile device when they arrive at the scene of an overdose. They indicate whether the case is fatal and whether naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdose effects, is administered. The data then populates a map on the backend.

“At that point of entry, we’re allowing that device to use the GPS … so it’s taking in the location, but it’s not storing the location. It won’t store a home address or anything like that,” Beeson said. “It will just store a dot on a map of geographic location. That data then populates on the backend database, which is our ODMap," he said. The password-protected database can be accessed only by Level II users -- public health officials, public-safety chief and law enforcement analysts.

The map shows all of the dots, or overdoses, that have happened in all locations using ODMap in real time.

“Our system will automatically evaluate a county or an area to isolate what a spike is,” Beeson said. “In a given 30 days, how many times are you reporting an overdose? Say in 30 days you recorded six overdoses three separate times, we’ll set that spike value at six. So on any given day in the future, if six overdoses are recorded in the system within a 24-hour period, you’re going to get an email from the system automatically.”

Those emails go to the chiefs and analysts, who will then know that a serious issue is occurring and where it’s happening. That’s leading some jurisdictions to formulate response plans, such as sending community alerts to schools, hospitals, community organizations and drug treatment centers when spikes occur to make caregivers more vigilant.

ODMap is now used by agencies across the country to better respond to overdoses.

Since using ODMap, Broome County, N.Y., sends peer recovery specialists with their officers to overdose responses so they can reach victims at the point of contact. “That’s really where we have a targeted approach to response,” Beeson said.

Additionally, ODMap produces weekly reports on what’s happening in an area, such as what day and hour the most overdoses are being reported.

Analysts at W/B HIDTA also study the data to draw more detailed conclusions. For example, Baltimore is Maryland’s drug distribution hub, so the counties around the city want to know when the city experiences an overdose spike. W/B HIDTA helps isolate that kind of information so everyone can be better prepared, Beeson said.

W/B HIDTA created the Esri-based ODMap in-house, runs the tool on its server and stores the data on its database. The first responders do not enter any personally identifying information such as victim names, so there are no concerns about Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance.

To get access to ODMap, jurisdictions must sign a memorandum of understanding stating that they can use their data any way they choose but cannot share it with others or the public, Beeson said. They must also sign a teaming agreement, which lets them view but not share others’ data.

W/B HIDTA initiated the program in January and concluded the pilot test in June. Currently 15 states and 48 counties report data, and ODMap has logged more than 3,400 overdoses.

Before ODMap, “there wasn’t a good system out there to track overdoses in real time across jurisdictions,” Beeson said. “Most jurisdictions are getting end-of-year medical examiner data about fatalities, and they’re not actively tracking nonfatal overdoses. We saw this as a problem.”

He sees opportunities to apply this technology in other ways in the future, such as overlaying data on shootings to find relationships between drug use and shootings. For now, Beeson is busy giving demonstrations of ODMap to bring more localities on board -- a task he’s happy to take on.

“Overdoses are the No. 1 accidental death in the country right now, and we’ve got public health officers still concerned about the Zika virus,” he said. “We should be talking about this. … This should dominate our public health dialogue.”

ODMap is also catching feds’ attention. In August, the Department of Health and Human Services selected it as one of 14 project ideas for its Fall 2017 Ignite Accelerator, HHS’ internal innovation startup program.

NEXT STORY: VA puts virtual beacons in medical center