Closing the agile culture gap

Connecting state and local government leaders

Agencies that want to take the agile route must close the culture gap by teaching skeptical colleagues how to function in the more experimental and trust-centered agile environment.

Government IT leaders who want their vendors to use an agile approach often face a serious obstacle: A yawning culture gap between the flexibility that technology providers enjoy and the highly regulated public sector. Government procurement typically isn't wired for agile.

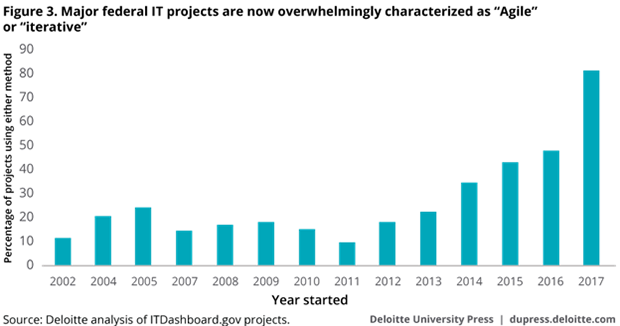

At the same time, interest in agile in government seems to be increasing. In an analysis of government data, we found 80 percent of large federal IT projects were described as “agile” or “iterative,” more than triple the rate of just a few years ago.

Agencies that want to take the agile route must figure out how to close the agile culture gap. They must teach skeptical colleagues -- from contract officers to budget officials to IT veterans steeped in the waterfall development method -- how to function in the more experimental and trust-centered agile environment.

There are five elements to the agile culture gap to consider:

1. The language gap

Agile speaks a language that seems all its own. “How many story points in this epic?” “What is the team’s velocity?” Instead of project managers, agile has product owners and scrum masters. For those not steeped in the agile methodology, this unfamiliar terminology can be daunting and may prompt a few eye rolls.

Agile advocates must demonstrate that the new language reflects a new way of doing things. Once colleagues understand the concepts behind these unfamiliar terms, they should be more prepared to use agile successfully.

2. The rules gap

Government procurement is often built on rules, regulations and documentation, which can make it an alien world for most agile practitioners, whose slogan might as well be: “Just get it done.”

Agile proponents should respect colleagues’ concerns about following procurement rules. At the same time, these rules generally allow some discretion, and procurement officers should be encouraged to use their expertise to comply with the rules while also allowing the agency and vendor to focus on the end result -- software that does what end users need.

3. The risk gap

CIOs seeking to use agile should be prepared to talk about risk. After all, whether using traditional waterfall or some form of agile development methodology, there is always a risk that a project will fail to deliver the intended results. Do contracting officers understand how risk is mitigated in an agile environment?

CIOs should also get contracting officials comfortable about the risks, explaining how the “trust and verify” approach in agile ensures the relationship is carefully monitored.

4. The trust gap

Traditional procurement contracts are designed to safeguard against cost overruns. In practice, these contracts can sometimes lead to software that meets specs without meeting the end user’s needs.

Agile entails some amount of trust. Vendor and client can develop trust by interacting closely and by holding frequent demonstrations to show progress.

The shorter timeframes in an agile approach can actually shift power to the procurer. Work sprints followed by demonstrations should keep the partnership on track. In other cases, an agency that issues small, incremental contracts can switch vendors at any iteration. Instead of loading a contract with penalties, agencies should design them to use the power of competition, keeping suppliers eager to deliver software that works.

5. The contract gap

A traditional procurement contract for a waterfall software development project covers everything -- prices, delivery and system performance -- often in minute detail. After awarding a contract, a client could wait months for the vendor to deliver -- sometimes with disappointing results.

Moving from a legalistic culture to a partnership culture is part of the agile journey. As the Agile Manifesto puts it, agile values “customer collaboration over contract negotiation,” and that means interactions between the client and vendor on a regular basis throughout the project are critical.

In agile development, a contract isn’t the key to success: contract management is. As often as every two weeks, the vendor should demonstrate how the project is moving along and talk about challenges that have come up since the last discussion. With this intimate, hands-on involvement, agencies can adjust their project plans as needed and hopefully avoid unpleasant eleventh-hour surprises.

Making the case for agile

Vendors often seem eager to sing the benefits of agile to the public sector. But their public sector colleagues in procurement, budgeting and even some of their own tech staff might be skeptical. They must work with these partners to get them comfortable with agile.