When the numbers aren’t enough: How different data work together in research

Important questions almost always can be answered better with a combination of quantitative and qualitative research.

This article was first posted on The Conversation.

As an epidemiologist, I am interested in disease -- and more specifically, who in a population currently has or might get that disease.

What is their age, sex, or socioeconomic status? Where do they live? What can people do to limit their chances of getting sick?

Questions exploring whether something is likely to happen or not can be answered with quantitative research. By counting and measuring, we quantify (measure) a phenomenon in our world, and present the results through percentages and averages. We use statistics to help interpret the significance of the results.

While this approach is very important, it can’t tell us everything about a disease and peoples’ experiences of it. That’s where qualitative data becomes important.

Let’s take the viral disease influenza (flu) as an example.

How many people had flu

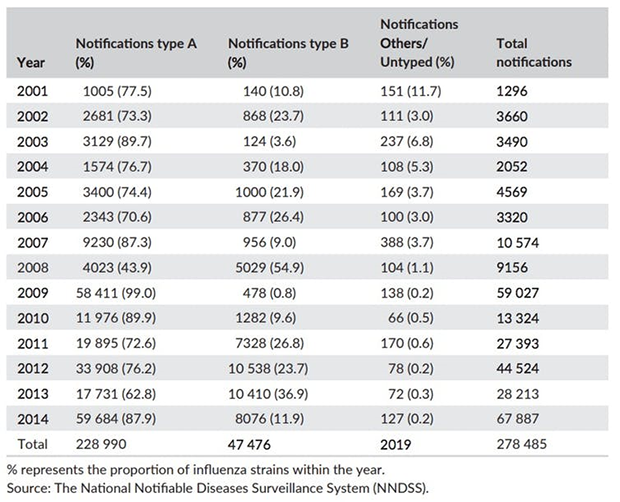

Quantitative methods tell me that over the period 2001 to 2014, Influenza B strain was responsible for an average of 17 percent of the notified cases of the flu in Australia each year, with most remaining cases caused by influenza A virus.

Delve even deeper, and we see variation in incidence from year to year. For example, in 2010, influenza B strain caused 9.6 percent of the notified influenza cases, while in 2013 it caused 36.9 percent of the cases.

These two virus strains -- influenza A and B -- are responsible for our seasonal flu each year, and circulate together in the community at varying levels over the seasons and by geography.

Each year the strains of influenza A and B change through evolution. So vaccinations need to be developed and administered every year to account for this.

Due to the rapid evolution of flu viruses, it makes sense for researchers to monitor influenza, so that steps can be taken to improve vaccines and reduce the number of people that get sick each year.

But that is not the whole picture.

Sometimes researchers want to know more than numbers. Sometimes it’s important to understand more complex issues in health care. Questions such as: how do people make decisions about their health, including risk of flu? What information do they use? Where do they find this information?

The answers to these questions are complicated. People apply reasoning to decisions based on many factors that are influenced by our social, cultural and political backgrounds.

The bigger story

Understanding and fitting the numbers into a bigger story is what qualitative research aims to achieve.

Qualitative methods include a range of techniques -- but interviews are one of the most common ways of gathering this sort of data.

Semi-structured interviews use a set of questions to guide the interview. This allows flexibility to explore ideas that arise during the conversation.

An audio-recording of the interview is transcribed and used for analysis, which is typically completed by at least two researchers independently to ensure they both come to the same conclusions.

Here’s another example from flu research that tells the story.

In a report published earlier this year, Australian researchers investigated how parents sought information during the 2009 pandemic of swine flu.

By completing mixed methods research -- research that includes both quantitative and qualitative research methods -- the researchers were able to gain a deeper understanding of their topic.

Mixed methods research

Applying a quantitative research method known as a cross-sectional cohort study, the researchers surveyed 431 parents recruited from childcare centers. They report that 90 percent of parents trusted the information that their doctor gave them about the influenza pandemic. Nurses (59 percent) and government (56 percent) were also trusted sources of information.

Only 7 percent of parents trusted information published about the pandemic in the media, and even less parents trusted information published by anti-vaccination groups (6 percent) and celebrities (1 percent).

Ranked list of who parents trust for swine flu information:

- Doctor

- Nurse

- Government

- Childcare center

- Family/friends

- Natural therapist

- Media

- Anti-vaccination group

- Celebrity

However, these numbers don’t tell us anything about why they did or did not trust these sources of information.

Here is where the qualitative research helps: a group of 42 parents were interviewed to ask more detailed questions.

Their responses revealed that even though parents trusted their GP as a source of information, they would go to their hospital’s emergency department for medical care during the pandemic.

Parents found that the way the media reported the pandemic generated fear among the community, which was not consistent with the mildness of the pandemic.

Finally, parents said they used the internet to supplement the information given by their doctors, nurses, and childcare centers; a finding missed in the quantitative study.

The full picture

Clearly, the information gathered during the qualitative research expanded and gave meaning to the numerical data gathered from the survey.

From the qualitative research we gained a greater understanding of where parents get information about influenza during an outbreak. This is vital information that can help health care workers ensure that parents have the information they want and need.

Traditionally there has been a tension between quantitative and qualitative researchers, with researchers on both sides arguing that their methods are superior to answer complex questions.

However, this tension misses the point that research questions of significant interest almost always can be answered better with the combination of methods.

NEXT STORY: How Mississippi IT Is Getting More Nimble