FBI database links murders to serial killer

Connecting state and local government leaders

The Violent Criminal Apprehension Program's system is helping investigators fill in details of the 90 murders Samuel Little has confessed to.

An FBI database helped connect one man to 34 of the 90 homicides he confessed to, which would make him one of the most prolific serial killers in U.S. history.

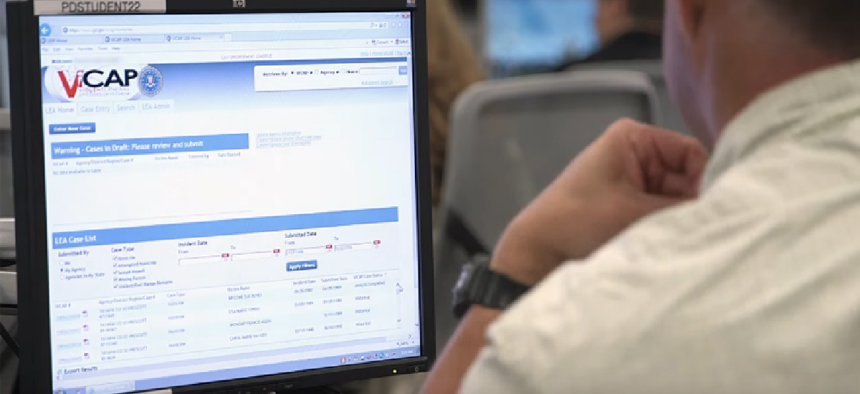

The Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (ViCAP) is a unit of the bureau whose database helps 2,500 users identify and stop violent serial criminals by linking seemingly unconnected crimes. The case of Samuel Little, who is linked to murders of women from 1970 to 2005, cracked wide open this spring when Little agreed to talk with investigators in exchange for a move to a different prison. Over the course of that interview, he confessed to 90 killings and offered some details on the people he murdered in cities across the country.

This case “is the perfect example of why ViCAP is so important,” ViCAP Program Manager Nathan Graham said.

Graham and his team have been working to modernize the ViCAP database -- moving it to the cloud and adding a new graphical user interface, improved search capabilities, integrated geospatial search and analysis, interactive timelines and anomaly detection. The program's cloud migration won a 2018 Government Innovation Award.

“We’re closer to moving that to production, getting to the cloud,” he said. “Once we get into the cloud, then obviously a lot of those nice-to-have enhancements … can start moving forward, but a lot of it now has been the backend infrastructure -- trying to get that in place," he said. "It is a pathfinder effort with the FBI. Being the first ones going through, you run into a lot of roadblocks and a lot of security issues that we have to overcome before we get to the end goal.”

ViCAP first became involved in the case after Little was arrested in 2012 in a Kentucky homeless shelter and extradited to Los Angeles, where he was wanted on a narcotics charge. DNA samples taken from him and uploaded to FBI’s Combined DNA Index System linked him to three cold homicide cases in the city.

Los Angeles officials charged Little with the homicides and “reached out to ViCAP and asked for analysis on those cases and Little himself -- being that they knew a lot about his background,” such as his long criminal history and transiency, said ViCAP Crime Analyst Christina Palazzolo, who worked on the Little case. They wanted to know if Little could be a suspect in other cases.

“Currently, you build essentially a SQL query on the backend,” Graham said. “You have a list of questions you want to search, you build your search parameters and then you’ll get a search results page, and it will list certain case information, the agency information, victim information … state, date and things like that," he said. The large set of results can be narrowed down, and ultimately you can do what we call a custom column. You can pull out whatever information in each case and build essentially an Excel spreadsheet to compare cases against your incident case.”

Palazzolo pulled information on Little's travels and activities and found the 1994 murder of Denise Brothers in Odessa, Texas. Based on Little’s travels and the modus operandi from that case, she determined he was a good suspect, but struggled to “pin anything back on him,” Palazzalo said.

She worked with Texas Ranger James Holland, an expert in interviewing psychopaths and sociopaths, and Angela Williamson, senior policy adviser and ViCAP liaison at the Justice Department, to set up an interview with Little in May. It was then that he made his confessions.

“That’s when the hunt really began for those other cases,” Palazzolo said. “As he was detailing these other cases, the ones that were in ViCAP, we found those pretty easily, pretty quickly. Even those that had a two- or three-sentence narrative, it was enough that everything was lining up with what he was saying. Those were pretty easily corroborated.”

For the cases that weren’t in the database, she relied on ViCAP liaisons, known as law enforcement agency managers, at agencies in the cities and counties where Little said he’d killed. Even if officials didn’t have cold cases that matched what he said, they could connect her with neighboring jurisdictions that might not have LEA Managers. “The networking that ViCAP does that they maintain and that we were able to tap into -- that was priceless,” Palazzolo said.

This information sharing was the crux of the case, she said, adding that Little confessed to crimes across 20 states. “We probably reached out to about from five to 10 different agencies per confession, so that’s a huge amount of information sharing,” she said.

The attention the Little case has brought ViCAP will make the database stronger and likely help find other criminals in other cases, Graham said, because the unit is working on a back-end learning system that is currently being tested. “When you have a large series like this that we know is connected, it really strengthens that learning process,” he said, adding that ViCAP has seen an uptick in requests for access to the database since news of the case broke.

“Our hope is that both agencies and even government entities will see just how powerful the database is, what we can do when we have the information, the impact we can have, the justice that we can bring to the victims and their families, some of whom have been waiting for answers for 40 years,” Palazzolo added. “Our hope is that it will generate more participation from agencies nationwide, that they’ll start entering more cases in and lead to more successes.”