How Libraries are Embracing Artificial Intelligence

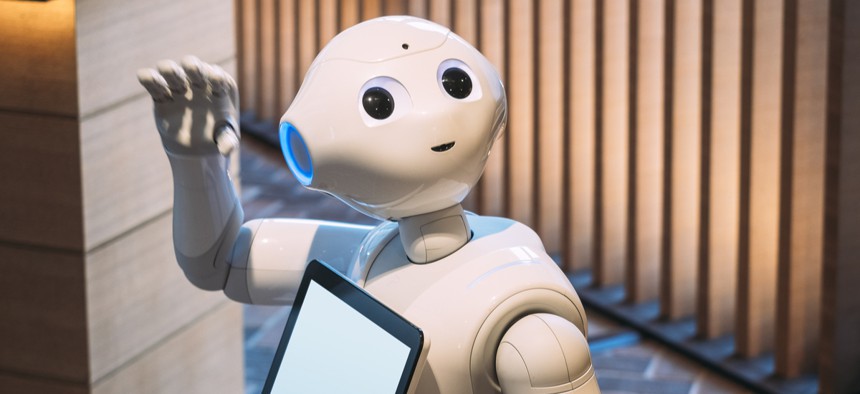

Roanoke County Public Library was the first in the country to acquire Pepper, which had been primarily used in retail and business environments. Shutterstock

A humanoid robot named Pepper helps teach coding at Roanoke County Public Libraries, one of many branches across the country embracing the emerging technology.

In Roanoke County, Virginia, a trip to the public library might include reading, online research, 3D printing—and, since last summer, the opportunity to chat with Pepper, a 4-foot-tall humanoid robot who sings, dances and teaches coding classes.

The Roanoke County Public Library was the first public system in the country to acquire Pepper, a decision made by staff members during a strategic planning session that focused largely on how the library hoped to evolve in a modern world increasingly focused on technology. During that discussion, someone mentioned that they’d heard of a robot named Pepper.

“It kind of captured imaginations,” said Shari Henry, director of library services. “So at one point I went to my office and said, ‘See what we can do. See if we can get that robot.’”

The robot, manufactured by SoftBank Robotics, had been primarily deployed as a greeter and receptionist in hotels, stores and banks, although a K-12 educational model was also available through RobotLAB, a separate company. Developers there had been interested in working with a library, Henry said, and after a video call with the CEO, the two groups decided to work together.

Pepper was purchased by the local nonprofit Friends of Roanoke County Public Library after Henry and several staff members gave a presentation explaining how the robot could help the library accomplish its long-term goals. Those included making advanced technology accessible to everyone, and continuing to educate consumers about data privacy and storage.

“We said, ‘We can’t promise you that this isn’t risky. It’s bleeding-edge technology, and we acknowledge that,’” she said. “We tried to answer all of their questions. I think the final thought was that it would be cool, especially for children and for special-needs children in particular.”

Pepper debuted at the library last August, telling jokes to patrons, posing for selfies and answering questions. The robot’s repertoire expanded quickly to include STEM presentations and coding classes. These give groups—from children to retirees—the opportunity to program Pepper to perform certain tasks, such as reading a story or participating in chair yoga.

“The classes pull up Choregraphe, a computer language that’s proprietary to Pepper,” Henry said. “And they decide what they’re going to have Pepper do. It’s a tangible outcome, they see it happen. There’s something that Pepper brings out in you that just feels very powerful, and for the rest of their lives these groups can say they were part of coding this robot to do X for the community.”

Henry envisions even more uses for Pepper in the future, including more educational programs and making the robot part of curriculum to broach sensitive topics like drugs and suicide with teenagers. The technology may seem advanced for a library, but branches across the country are embracing artificial intelligence as a community tool, ensuring access and educational opportunities for patrons who may not otherwise have the chance to experience it. Those measures range from interactive art installations to augmented reality displays to allowing residents to check out AI learning kits for home use.

“Libraries are not tech experts—but we are experts in how community members learn, connect, pursue careers and address civic issues,” said Curtis Rogers, spokesman for the Urban Libraries Council, which launched an AI initiative for its members earlier this year. “As the AI revolution transforms every aspect of our lives, libraries are stepping up to ensure they can continue to fulfill their essential role as anchor institutions and lead their communities forward.”

Achieving that goal is not without risk, Henry noted. For example, earlier this year Roanoke’s library system deployed a series of tiny robots at multiple branches, only to see the parent company go out of business, leaving the future of the devices somewhat in doubt (for now, the company is still providing support for existing machines). But utilizing Pepper generated excitement within the community, garnered publicity for the library and inspired staff members to aim bigger in their goals—outcomes that more than justify the potential hazards, she said.

“It’s worth the risk because libraries are about innovation. So it's okay if it's hard and if sometimes things do not go according to plans,” she said. “It’s made us drive a little higher, and that’s been great for us and for what we do.”

Kate Elizabeth Queram is a Staff Correspondent for Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Researchers tap LiDAR-enabled indoor mapping for responders