With Census Count Over, Concerns Linger About Accuracy

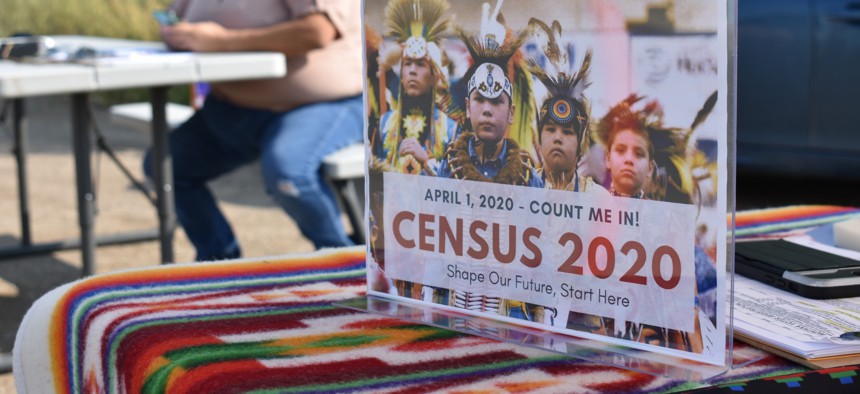

A sign promoting Native American participation in the U.S. census is displayed as Selena Rides Horse enters information into her phone on behalf of a member of the Crow Indian Tribe in Lodge Grass, Mont. on Wednesday, Aug. 26, 2020. AP Photo/Matthew Brown

Community groups raced to get more people to complete census questionnaires before the count ended Friday, but they still believe many were missed after the deadline was pushed up.

The abrupt halt of the 2020 Census count this week ended with a flurry of last-minute phone calls and text messages from outreach workers in California, desperate to connect with residents who hadn’t yet completed the questionnaire.

Over the last two months, the Los Angeles-based Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights ran a phone banking operation that made more than 50,000 calls and sent more than 280,000 texts to residents in immigrant communities to encourage them to complete the 2020 questionnaire, said Esperanza Guevara, the organization’s census campaign manager. Those efforts continued in earnest through the last day of the census count, with advocates reaching several families who had still not completed the forms.

“There are still so many more neighbors that we have to call and text who unfortunately we are not going to have time to reach,” Guevara said, speaking with reporters on a call Thursday.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled this week that the Trump administration could stop the decennial count, halting the Census Bureau’s enumeration activities more than two weeks before its previously scheduled deadline. Counting operations came to a close at 6 a.m. Friday EST.

This year’s census count has been fraught with complications that advocates fear could result in an incomplete enumeration of the U.S. population. The Trump administration fought unsuccessfully to include a citizenship question, which immigrants’ rights groups said led to fear and mistrust among immigrant communities and the coronavirus pandemic delayed in-person efforts to encourage people to participate.

Further threatening to complicate this year’s count, the Supreme Court on Friday said it would review the Trump administration’s plan to exclude undocumented immigrants from the census count used to divvy up the House of Representatives seats given to each state. A lower court previously ruled that the president cannot leave undocumented immigrants out of this count. Arguments in the case will be heard Nov. 30.

The 2020 census will be crucial in determining how hundreds of billions of federal dollars are divided among states and localities in the years ahead for programs that help provide money for highway construction, food stamps and health care for the elderly and the poor. Census data is also used for political redistricting at all levels of government.

“One of the biggest concerns with the census shutting down operations earlier is that millions of people may be left uncounted,” said Keshia Morris-Desir, the census project manager for Common Cause.

In California, Guevara estimates that some 580,000 Latinos are at risk of not being counted and the state could lose $1.5 billion in federal funding as a result of an undercount of the state’s population.

The Census Bureau said more than 99.9% of housing units have been accounted for in this year’s census, but experts caution the figure can be misleading. Census takers who are unable to make contact with residents may conduct a proxy interview with a neighbor or landlord to account for a household, or may check building addresses but not individual apartment units.

“They are making fairly extravagant claims about how good it is, but they haven’t put out any data about what that is based on,” said Andrew Beveridge, a sociologist and demographics expert and retired Queens College, City University of New York professor.

The national self-response rate, or people who completed the census questionnaire online, by mail or by phone before interaction with enumerators, is 66.9%.

While this year’s census enabled residents to respond online, making it easier to count some parts of the country, hard-to-count communities have not been responding at higher rates, said Beth Lynk, the Census Counts campaign director at the Leadership Conference for Civil Rights.

“As of today, we know that the percentage of tracts that are predominantly people of color are behind where they were in terms of self-response in 2010,” Lynk said.

Specifically, 68% of predominantly Black census tracts, 67% of predominantly Hispanic tracts, and 80% of predominantly Native American and Alaskan Native tracts have lower self-response rates than in 2010, she said.

Door-to-door enumeration efforts had boosted response rates, Lynk said. But Friday’s cut off put an end to that.

“That disparity was going down and it was our hope with more time we and advocates could have gotten that number and that disparity down further,” she said.

Even though the census count is over, experts say litigation over the Trump administration’s handling of the census is likely to continue.

On one hand, challenges by local governments are nothing new. State and local governments have traditionally been able to challenge census population counts after they are complete, Margo Anderson, a retired University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee professor who has extensively studied the U.S. Census.

“The state and local governments have been challenging the competence of the federal government to count the population since the mid-19th century,” Anderson said.

But some may seek to challenge other aspects of how the data is used, such as in election redistricting, or to ensure the Trumpadministration is transparent about the final data it turns over to Congress, Beveridge said.

“I think we are heading into a massive period of litigation or an attempt to fix it if there is a new administration,” he said, adding that if former Vice President Joe Biden wins the election next month a new administration could go as far as to push for another census count.

Andrea Noble is a staff correspondent with Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: To Better Address Covid, States Need to Use Data Better