Demography Is Not Destiny

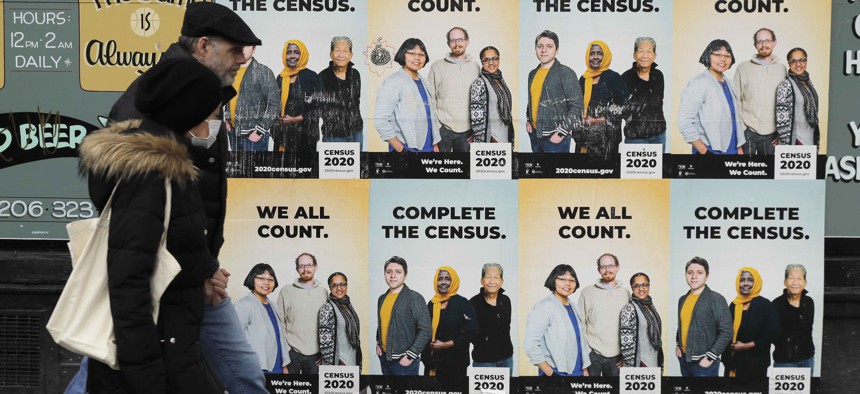

In this Wednesday, April 1, 2020 file photo, People walk past posters encouraging participation in the 2020 Census in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood. AP Photo/Ted S. Warren, File

COMMENTARY | New numbers provide a reminder of the fluidity of American identity.

This article was originally published in The Atlantic. Sign up for their newsletter.

In the more racist corners of the mainstream right, the 2020 census findings that the white American population has declined are cause for panic.

“Democrats are intentionally accelerating demographic change in this country for political advantage,” the Fox News host Tucker Carlson insisted on Friday, treating the results as confirmation of this conspiracy theory. “Rather than convince people to vote for them—that’s called democracy—they’re counting on brand-new voters.”

Carlson, it’s worth noting, has it wrong—voters who are not white are no less persuadable than those who are. If Republicans want to win over those constituencies, nothing is stopping them beyond their own nativism. And any read of the census results that assumes the growing diversity of the United States will simply redound to one party’s benefit is likely mistaken.

Political parties and identities are not static, and few concepts are as elastic as the invention of race, in particular the category of “white,” which is defined not just by looks and ancestry, but also by ideology and class. The fact that fewer Americans identify as white in the 2020 census than did 10 years before does not spell doom for the Republican Party, nor does it herald an era of political dominance for the Democrats, despite the forlorn cries of those who are committed less to conservatism as an ideology than the political and cultural hegemony of those they consider white.

[Read: The myth of a majority-minority America]

American nativism has a long and ugly history. At the turn of the century, fears that immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe would flood the country with an inferior genetic stock led to a panic. The result was a series of racist and anti-Semitic immigration laws designed to preserve America’s supposed “Anglo-Saxon” character. The composite white American identity that emerged after World War II was not yet dominant—the popular belief was that there were many white “races.” Europeans of Jewish, Italian, and Russian extraction were “beaten men from beaten races” who lacked the Anglo-Saxons’ inherent faculty for self-government. Immigration had to be curtailed before the old, “native” white American stock committed “race suicide,” the ideological precursor to the “white genocide” and “Great Replacement” conspiracy theories, themselves historical inversions of the realities of European colonialism.

These ideas are consonant with a particular worldview popular with certain social conservatives of virtually every era—that today’s population is coddled, weak, and degenerate compared with generations past. “The first requisite in a healthy race is that a woman should be able to bear children just as the men must be able to work and fight,” Theodore Roosevelt wrote in a letter in 1901. As Thomas G. Dyer writes in Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race, the 26th president feared that old white American stock had grown decadent in its luxury, and would soon lose the “war of the cradle” to inferior races.

As it happened, the race pseudoscience of the time, which denigrated certain Europeans and nonwhite people as mentally deficient and unfit for self-government, aged poorly. The Southern and Eastern European immigrants once deemed genetically inferior were raised into the American mainstream and middle class by a racially stratified New Deal welfare state, and became so assimilated that some of their descendants today repeat versions of the old dubious theories to justify their suspicions about new generations of immigrants. Because race is a biological fiction, its categories are shaped by power and social dynamics, not hard laws of science.

The history of how America has defined who counts or identifies as “white” illustrates this reality, and reveals why drawing broad political conclusions from the census is impossible. As white Americans in the North and South retreated from the brief experiment with multiracial democracy after Reconstruction, the question of who was defined as “white” gained critical salience. Ian Haney López writes in White by Law that from 1878 to 1952, American courts struggled mightily to define the borders of American racial identity in legal terms. “A court in 1909 ruled that Armenians were White, even though their origins east of the Bosporus Strait, the official geographic line between Europe and Asia, made them at least geographically Asian,” Haney López observed. “More perplexing still, judges qualified Syrians as ‘white persons’ in 1909, 1910, and 1915, but not in 1913 or 1914; and Asian Indians were ‘white persons’ in 1910, 1913, 1919, and 1920, but not in 1909 or 1917, or after 1923.”

Reviewing a citizenship application from a Syrian immigrant, one exasperated federal judge complained that the term “white person” was “about as open to many constructions as it possibly could be.” Another wrote that such immigration laws existed because “the objection on the part of Congress is not due to color, as color, but only to color as an evidence of a type of civilization which it characterizes. The yellow or bronze racial color is the hallmark of Oriental despotisms.” That the American racial hierarchy he was adjudicating was itself a form of despotism did not occur to him.

In 1922, the Supreme Court decided that Takao Ozawa, who was born in Japan but had lived in the United States for decades, was ineligible for naturalization because, despite his light skin, he was “clearly of a race which is not Caucasian.” But when a few months later Bhagat Singh Thind, a Sikh veteran of World War I who had served in the U.S. Army, argued before the Court that he was technically Caucasian under the prevailing “scientific” definition of the term, the justices sniffed that “the words ‘free white persons’ are words of common speech to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man, synonymous with the word ‘Caucasian’ only as that word is popularly understood.” In short, race is whatever those with the power to define it say it is.

“Science’s inability to confirm through empirical evidence the popular racial beliefs that held Syrians and Asian Indians to be non-Whites should have led the courts to question whether race was a natural phenomenon,” Haney López wrote. “So deeply held was this belief, however, that instead of re-examining the nature of race, the courts began to disparage science.”

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted American citizenship to Texans of Mexican descent, but that did not mean that Anglo Texans treated Mexican Americans as equals. Texas still maintained a system of “tripartite segregation” in public schools, where Latino students were segregated from Black students, who were also segregated from white students. A group of Mexican American parents in the 1930s challenged this system not on the grounds that segregation was wrong, but on the basis that their children were being denied the rights afforded to “other white races.” As Benjamin Márquez writes in LULAC: The Evolution of a Mexican American Political Organization, the publication of the League of United Latin American Citizens described Mexican Americans in 1932 as “the first white race to inhabit this vast empire of ours.” In those early days, LULAC was “careful not to question the system of racial categories itself but the fact that Mexican Americans were placed in an inferior category.” A different mode of advocacy emerged in the mid-20th century with the Chicano movement, which encouraged Mexican Americans to think of themselves as having a distinct identity, rather than identifying as white.

As an example of how malleable such borders are in our own time, the 2020 census found that “one third of Hispanics reported being more than one race, up from just 6 percent in 2010,” which means that “Hispanics are now nearly twice as likely to identify as multiracial than as white.” Americans who “identified as non-Hispanic and more than one race rose the fastest, jumping to 13.5 million from 6 million.” As a way of illustrating the fact that this does not have straightforward political implications, Donald Trump, who began his 2016 campaign by denigrating Mexican immigrants, did better with Latino voters in 2020 despite a larger percentage of them identifying as multiracial.

Neither the fiction of race nor the political identities that emerge from it are necessarily permanent. The party of white supremacy can become the party of civil rights. Yesterday’s “beaten men from beaten races” can help rescue the world from fascism, just as New Deal stalwarts can someday become Reagan Democrats. The pro-immigrant communities of yesteryear can become the nativists of the future. The radicals of the past can grow into the middle- and upper-class establishment. Those once seen as bearing the “hallmark of oriental despotisms” may become tomorrow’s “model minorities.”

Nevertheless, these definitions can linger. During the period in which being either white or Black was a prerequisite for naturalization, prior to the 1920s immigration restrictions that barred immigrants from Africa and Asia from seeking citizenship, many immigrants in these cases sought citizenship by arguing that they were white, but as Haney López writes, none seems to have ever done so by identifying as Black. To do so would have been almost like not being a citizen at all.

[Read: The end of white America?]

“In race talk the move into mainstream America always means buying into the notion of American blacks as the real aliens. Whatever the ethnicity or nationality of the immigrant, his nemesis is understood to be African American,” Toni Morrison wrote in 1993. “A hostile posture toward resident blacks must be struck at the Americanizing door before it will open.” America has grown from a nation founded by slave owners to one that elected a Black man president, but in the aggregate, elements of its traditional racial hierarchy have remained remarkably durable. Unfortunately, it is easy to imagine an outcome where America is more diverse, but where Black people continue to be denied equal political rights and economic justice.

The census may herald a more inclusive and harmonious future, or it may simply foreshadow yet another moment in American history when some borders shift while others remain closely guarded. But what the census cannot tell you is where lines of partisan identity will be drawn. It can tell you how Americans define themselves, but not how their politics flow from that definition. The census cannot tell Americans who they will become; that we must decide ourselves.

Adam Serwer is a staff writer at The Atlantic.