Cities tackle food insecurity with tech

Boston and Atlanta are closing the food access gap with tools that provides central sources for information.

In the wake of the pandemic, food banks around the country have seen unprecedented increase in new patrons, forcing local agencies and nonprofit organizations to reassess their approach to food insecurity.

According to the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, 13.8 million people were food insecure at some point in 2020, and the nonprofit Feeding America estimates that economic hardships associated with COVID-19 could ratchet the 2021 figures to 42 million Americans.

To counter this troubling projection, cities like Atlanta and Boston are using GIS apps and SMS chatbots that not only tackle the issue of food access, but better deliver information to those who are the most vulnerable: newly food insecure families.

“Families who had never navigated this problem before were suddenly facing food insecurity,” Atlanta Community Food Bank (ACFB) Marketing Data Analyst Nick DiSebastian said. “So we had all sorts of campaigns like billboards, TV and our SMS ‘Find Help’ map, to first gather information on where people were looking for food.”

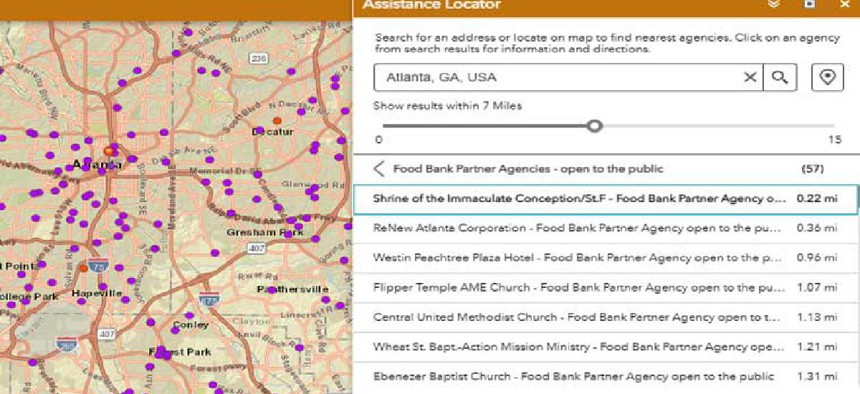

The Help Map, which can be accessed on the ACFB website or by texting FINDFOOD to a specific number, uses cloud-based Esri software to connect Greater Atlanta residents to three types of food assistance sites. These include over 700 partner agencies with regular schedules, mobile pantries that are open a couple days a month and Georgia Department of Education meal sites, which specifically cater to children under 18.

“We used Esri’s ArcGIS online platform, and specifically their Web AppBuilder, to improve the Help Map’s functionality to where you can input your address and set a search-distance radius,” DiSebastian said. “This offered us the opportunity to provide very updated results during a dynamic time, when hours of operation and locations were constantly changing.”

Previously, residents would have to call into the office and have the representative look up the information manually, DiSebastian said. The phone-based method is still available as a backup, but now, the ACFB staff can check the map using the caller’s address and forward the exported data.

Boston also recently launched its own initiative, an SMS chatbot and food donation platform, to strengthen the citywide food access network. Mayor Kim Janey and the Office of Food Access (OFA) unveiled these tools in September following the success of its initial iteration, an emergency grocery delivery service that operated during the height of the pandemic.

The SMS solution was specifically designed to improve access for those that do not have a stable connection to the internet, OFA Outreach and Communications Director Catalina Prada Valderrama said. While improving the technological capabilities of the application was a consideration, the needs of the community came first.

“We are looking into how to integrate more things, but we didn’t want to impose technology just for the sake of doing so,” Prada Valderrama said. “It is still a work in progress.”

In Atlanta, improving the ACFB Help Map’s functionality is the next step, DiSebastian said. Right now, the data being collected by the platform only reflects usage, or how often the map is being accessed. A new tool that could provide more accurate information about the local food gap is already in the works.

“We are in the midst of implementing a custom widget that is going to track where people are searching for help,” he said. “We saw a huge increase in usage during the pandemic, which was heartbreaking and encouraging at the same time, because it meant more families were food insecure but that they were also using our resources. With the improved data, this new widget can better help us fill the current [food access] gaps in our communities.”