New method makes traffic prediction faster

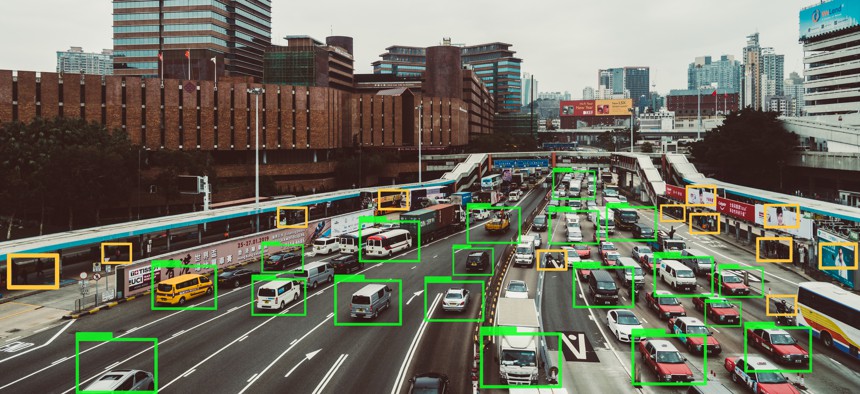

AerialPerspective Images / Getty Images

Researchers at NC State tested a modified algorithm to help streamline complex computing challenges required for traffic forecasting.

A new method reduces the computational complexity of traffic models to make them operate more efficiently, according to a new study.

Models that predict traffic volume for specific times and places are used to inform everything from traffic-light patterns to the app on your phone that tells you how to get from Point A to Point B.

“We use models to predict how much traffic there will be on any given stretch of road at any specific point in time,” says coauthor Ali Hajbabaie, an assistant professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at North Carolina State University.

“These models work well, but the specific forecasting questions can be so computationally complex that they are either impossible to solve with limited computing resources, or they take so long that the prediction only becomes available when it is no longer useful.”

The researchers’ starting point for this work was an algorithm designed to help streamline complex computing challenges, but they found they couldn’t apply it directly to traffic problems.

“So, we modified that algorithm to see if we could find a way to use it in models that predict how much traffic there will be in a specific place and time,” Hajbabaie says. “And the results were gratifying.”

Specifically, the researchers came up with a modified version of the algorithm that effectively breaks the larger traffic forecasting model into a collection of smaller problems that can then be solved in parallel with one another.

This process significantly reduces run time for the forecasting model. However, the extent of the improved efficiency varies significantly, depending on how complex the forecasting questions are. The more complex the question is, the greater the improved efficiency.

The modified method also improves run time by allowing the model to recognize when it has reached a solution that is good enough—the solution doesn’t have to be perfect. Traditionally, models will run until they find an optimal solution, or one very close to optimal. But for most purposes, a result that is within 5%—or even 10%—of the optimal solution will work fine.

“Our approach here essentially sets error bars around the optimal solution and allows the model to stop running and report a result when it gets close enough,” Hajbabaie says.

The researchers tested the modified algorithm against a benchmark algorithm used in consumer software to address questions related to traffic forecasting.

“Our modified algorithm outperformed the benchmark in two ways,” Hajbabaie says. “First, our algorithm used far less computer memory. Second, our algorithm’s run time was orders of magnitude faster.

“At this point, we’re open to working with traffic planners and engineers who are interested in exploring how we can use this modified algorithm to address real-world problems.”

This article first appeared in Futurity. PhD student Mehrzad Mehrabipour is first author of the study in IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. Source: NC State Original Study