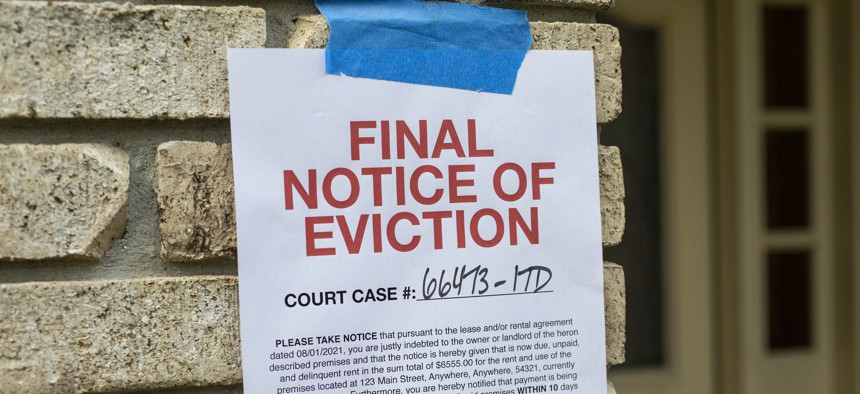

There’s one year left to turn the corner on evictions

KLH49/Getty Images

COMMENTARY | By taking advantage of ARPA funds, local leaders can better utilize eviction data to keep more people in their homes.

Before COVID-19 hit, the city of Alexandria, Virginia, did not track evictions. Information was available through publicly accessible court records posted online, but without time and resources to pull it down, process it and transform it into something useful, it might as well have not existed.

But as the coronavirus raged and concerns about a pandemic-driven “eviction tsunami” grew, a local legal aid organization and a few pro-bono volunteers began manually transcribing eviction court records into an Excel spreadsheet, painstakingly documenting each court case, recording the amount of back rent owed and where evictions took place. They shared the data with community partners throughout the city so they could quickly identify and contact those in need of rental assistance.

After a moratorium on evictions went into effect in September 2020, housing advocates and legal aid providers used the spreadsheet to determine when to show up for eviction hearings and inform tenants of their rights, often stopping the eviction from moving forward.

What started as a small data collection effort to help stem the tide of pandemic-era evictions turned into a sustained effort by the city of Alexandria to maintain a local eviction database. In spring of 2021, the city used American Rescue Plan Act funds to hire a full-time data analyst to turn the informal information gathering effort into a regularly updated eviction dashboard.

Alexandria’s dearth of pre-pandemic eviction data is not unique. But the city’s solution is: Using ARPA State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, or SLFRF, to improve access to and use of this data can be instructive for the thousands of other jurisdictions nationwide that received portions of the $350 billion authorized by the Congress in 2021 to respond to the far-reaching public health and economic impacts of the pandemic.

Improving access to and use of critical eviction data is an allowable use of SLFRF dollars, but the clock is ticking. There is only one year left to obligate what remains of these funds.

Each year, landlords file millions of eviction cases in county and small claims courts across the country. Court records from these cases are the primary data source on evictions, and they typically contain the names and addresses of landlords and tenants, the date an eviction filing and judgment takes place, occasionally information about the amount of back rent a tenant owes and whether they had attorney representation.

When local leaders can access and analyze this information, they can develop policies and deliver programs that keep people housed. In Orlando, for example, local officials analyzed eviction addresses to target the hardest-hit neighborhoods for door-knocking campaigns to alert residents of rental assistance help. The Tempe City Council in Arizona stood up a Spanish language legal aid clinic when the data revealed that neighborhoods with large immigrant populations were at highest risk for evictions. And in Indianapolis, researchers at Indiana University-Purdue used local eviction filings to show that a small number of corporate landlords were responsible for most of the city’s evictions.

But these uses of data are the exception, not the rule. There is no federal eviction database, and most local courts lack the mandate and funding to collect, aggregate and share court eviction data.

Court eviction data is too often messy, incomplete and inaccessible, leaving court, government, and community leaders without the basic information they need to develop data-driven policies to keep people stably housed.

The obstacles are multilayered. Some courts either don’t digitize eviction records at all, or they digitize them locally onto the computers of court staff, often in scans of handwritten documents, or PDFs from which information can’t easily be extracted. That painful reality inspired a four-person team from the University of North Carolina Greensboro’s Center for Housing and Community Studies to spend the last year extracting data from PDF eviction records provided by court staff and manually entering information into a database so they could better understand local evictions.

Other courts feed evictions into their case management systems but do not make these databases available to the public or to city housing department staff, rental assistance administrators and others who could use this information in their day-to-day work. Even when eviction databases are purportedly public, locating them and gaining access requires a significant investment of time and resources.

And when courts do make data available, local housing departments too often don’t have the human and financial resources to clean and analyze it. In Fort Wayne, Indiana, for example, the city’s community development office worked with the Allen County Court to obtain local eviction records. But cleaning those records and converting them into a usable format took the office’s only GIS analyst weeks, making the approach unsustainable over time.

Developing data-driven policies and programs that prevent housing loss and stabilize families and communities is essential. Doing so will require courts to build the capacity to collect, standardize and share eviction data and local leaders to have the ability to analyze and act on it.

Funding Options

The good news is that federal funds can help. SLFRF dollars were designed to be flexible, and improving the collection, sharing and use of court eviction data can be an allowable use of these funds. The $350 billion appropriated by ARPA for SLFRF must be locally obligated by the end of 2024—and then spent by the end of 2026—or state and local recipients must return unobligated funds to the feds. As of March 2023, nearly half of those funds were still unobligated.

Courts and local governments with remaining SLFRF funds can hire dedicated staff to clean, compile and analyze court eviction data, just as Alexandria did. They can conduct a local eviction data needs assessment, identifying data gaps and strategies for filling them. Depending on what eviction data looks like in their jurisdictions, local leaders can either use the funds to manually convert public records (whether from a public website or from physical files) into a usable electronic format, or they can automate manual processes required to work with court data, such as cleaning and verifying address information, aggregating case files.

The funds can also be used to develop processes for data-sharing across government agencies and promote interoperability of data systems. Courts can upgrade their case management systems, standardize the way court data is collected and recorded or train court clerks to uniformly record eviction information. Ideally, they would stand up a centralized entity to collect, house and analyze eviction information.

Local leaders whose cities have already obligated or used their SLFRF dollars can check whether their county or state has funds remaining.

Even where 100% of all relevant jurisdictions’ SLFRF has been obligated, there may still be opportunities to tap these funds to build an eviction database and evaluation capacity. For example, for courts, housing agencies, universities or housing services nonprofits that received funds for activities expressly allowed by federal guidance—including to “reduce backlogs,” or “case management related to housing stability” or “eviction prevention or eviction diversion programs”—the precise budget may have flexibility to include systems for tracking evictions and data analysts to guide new policy.

Jurisdictions could also consider pursuing other federal funds administered by state, tribal and local governments that could permit spending on an eviction database. For example, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Community Development Block Grants guidance expressly allows funds for “data gathering” and “planning activities” to advance CDBG housing goals for low- and moderate-income people. In other words, multiple funding streams could be explored with local administrators of federal funds.

It is said you can’t fix what you don’t measure. Evictions across the country are back to pre-pandemic levels, and millions of people are forced from their homes each year. If local leaders hope to pass data-driven policies that keep more people stably housed, then they must improve how they track and understand evictions. Luckily, there are funds to do this. Now, they just have to act.

Yuliya Panfil is a senior fellow and director, Future of Land and Housing Program, with New America.

Karen Lash is a non-resident fellow at the Tech Institute and a senior fellow at the Georgetown Justice Lab.

NEXT STORY: Expungement backlogs swamp courts