How NASA beamed Mona Lisa to the moon, one pixel at a time

Connecting state and local government leaders

The space agency has been using its Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter to map the moon's surface, which made it a perfect platform to test out laser communications across space.

Remember when Dr. Evil put a (air quotes) laser (air quotes) on the moon in an attempt to destroy the United States? NASA also has ideas involving lasers and the moon, only this time, the goal is to test out new methods of space communication by beaming an image of the Mona Lisa to the moon.

Space is mostly empty, which for communications can be good and bad. It’s good because other than a planet here and there, and perhaps an asteroid, there isn’t much to block a signal. On the down side, there isn’t much infrastructure outside of Earth’s orbit. Right now, NASA has to communicate with all of its space probes and exploration vehicles using the Deep Space Network, which relies on low-bandwidth radio waves. It can take up to 15 minutes to send commands as far as Mars, and just as long to get a response back.

The answer might be lasers, which can carry information optically more easily in space than here on Earth. There isn’t much to block the line of sight of a laser in space.

NASA has a satellite circling the moon called the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which is already equipped to accept laser signals though its Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA), which is mapping out the entire surface of the moon. So NASA figured that in addition to sending along the normal tracking data, it could beam regular information, or even a photo, at the same time.

"Because LRO is already set up to receive laser signals through the LOLA instrument, we had a unique opportunity to demonstrate one-way laser communication with a distant satellite," wrote Xiaoli Sun, a LOLA scientist at NASA Goddard in a release following the achievement.

For her journey, the Mona Lisa was reduced to 152 by 200 pixels. Each pixel was sent to the LOLA using a laser during the brief window when the tracking and mission data wasn’t using the beam. NASA specifically had 4,096 of those brief pauses to work with. How much to darken a pixel was determined by delaying the information pulse. The time difference between when the satellite expected to receive the data and the actual time the data arrived determined how much shading was needed for each pixel.

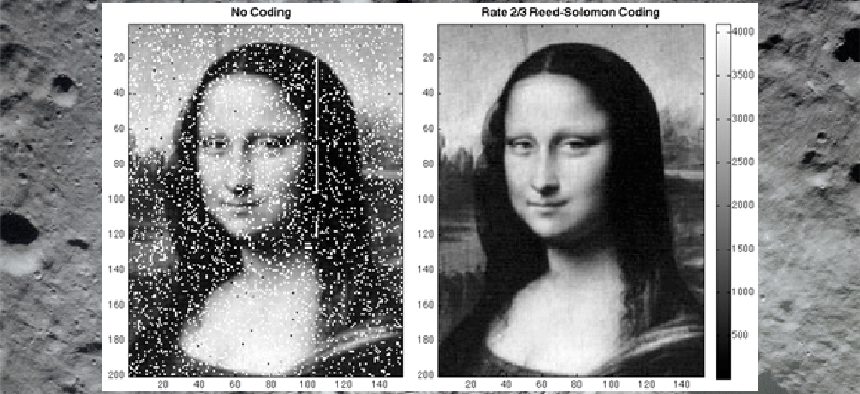

Because of the Earth’s atmosphere interfering with the laser, the transmission wasn’t perfect. However, using the Reed-Solomon error correcting code, the same type used to keep CDs and DVDs from skipping, NASA was able to perfectly reassemble the photo on the other end. The Mona Lisa was now orbiting the moon, 240,000 miles away. The transfer rate was equal to about 300 bits per second.

While 300 baud modems are far from high-tech these days, the experiment shows that lasers can be used for effective communication, even over very long distances. They are also highly directional, compared to radio waves that radiate out from their source. Theoretically, that could allow for two-way communications using lasers in the future, with each beam sitting right beside another. NASA is already thinking about using lasers, at least as a backup, for future mission communications.

"This is the first time anyone has achieved one-way laser communication at planetary distances," said LOLA's principal investigator, David Smith of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "In the near future, this type of simple laser communication might serve as a backup for the radio communication that satellites use. In the more distant future, it may allow communication at higher data rates than present radio links can provide."

For now, we can simply marvel that the Mona Lisa has become the Moona Lisa, the first piece of classical art beamed by laser into space.

NEXT STORY: The military wants to step up its training game