How a game helps improve robotic space flights

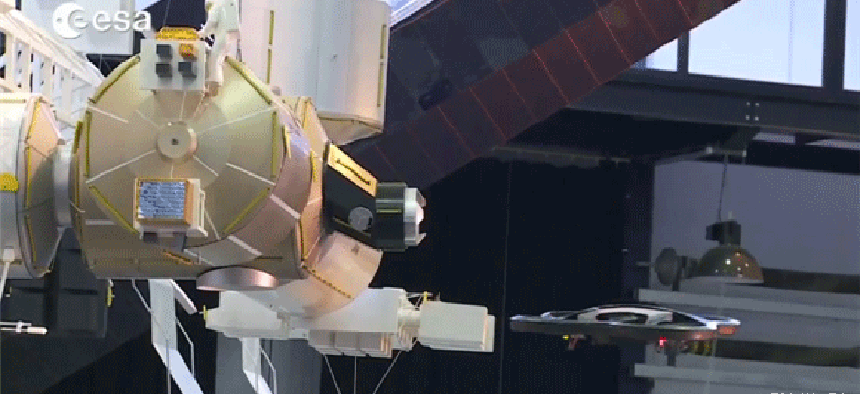

The European Space Agency combines real-world and virtual components with AR.Drone to improve its software for space flight and docking with the International Space Station.

I’m not sure how many hours I wasted in my youth playing Lunar Lander, or how many times I screamed at the computer that it was cheating. It probably wasn’t, but trying to land a spacecraft on a jagged planetary surface using only a tiny fuel reserve isn’t easy.

Thankfully, I can now claim that I wasn’t wasting time. Instead, I was developing a unique skill set that could one day make robots in space more efficient.

Like many U.S. agencies, the European Space Agency is experimenting with gamification, with an eye toward making processes and devices more efficient or to solve complicated problems with crowdsourcing. In this case, ESA is attempting to improve the way flying robots are controlled in space.

To get a real sense of how robotic flight works, the researchers needed both a virtual and a real-world component. The virtual component is used to test out the controls, but the real world robot was needed to show how real, physical flight controls would actually perform.

Thankfully, they found the AR.Drone, which has sold about half a million units around the world. There is even a large community of flyers who make apps for the device and videos of their flights. Equipped with two cameras, the midget drone flies around on four rotors and can be steered by any iOS device.

ESA created an app that lets users print out strips of paper that can be used as targets for the AR.Drone. Whatever a user attaches the strip to becomes the International Space Station in the game. So a chair or the side of a house work just fine as space station stand-ins. Then, using an iOS device, users attempt to dock the drone with the space station. The app feeds the user positional data, and the screen displays the docking port on the ISS.

So players are juggling both the physical robot in the real world and the virtual landing instructions within the game. If players can keep the two in sync, they will successfully dock the craft.

ESA then collects the scores of the players and their positional data. All that information will be used to help refine the software used by actual engineers trying to dock spacecraft with the ISS. The more people who play the game, the better that subset of data will be in helping to improve robotic operations.

ESA may release other versions of its docking-type games, including one where the Rosetta probe attempts to land on the 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet, an event scheduled to happen early next year.

And unlike the Lunar Lander game, I’m pretty sure this new app won’t cheat me out of my victory!