Tiny 3D printed battery could power devices of the future

A research team prints a lithium ion battery the size of a grain of sand out of electrochemical inks, opening the door for microscopic medical implants, communications devices and other gear.

A team of university researchers have taken 3D printing to the nanoscale, printing a lithium ion battery the size of a grain of sand and opening up new possibilities for tiny medical, communications and other devices.

Based at Harvard University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the researchers were able to print interlocked stacks of hair-thin “inks” with the chemical and electrical properties needed for the batteries, according to a report by the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

It’s a breakthrough in the development of microbatteries, which to date have used thin films of solid materials that lacked the juice to power devices such as miniaturized medical implants, insect-sized robots and miniscule cameras, the researchers said. Small, 3D-printed batteries also could help propel development of wearable technology, decreasing the weight of products like Google Glass or smart-phone wrist watches.

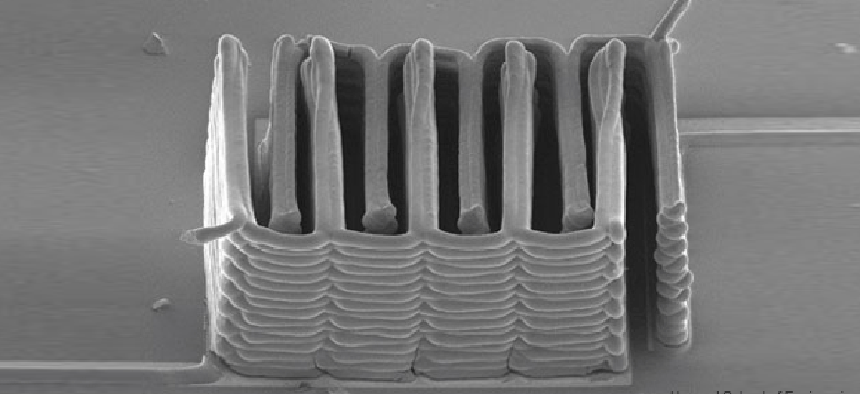

The research team tackled the power problem by using a custom 3D printer to produce precise, tight stacks of ultrathin battery electrodes. The key was developing the printable electrochemical inks — one for the anode and one for the cathode, each made with nanoparticles of lithium ion metal oxide compounds, the researchers said.

After printing, they put the stacks into a container, added an electrolyte solution, then measured the power of the finished product. “The electrochemical performance is comparable to commercial batteries in terms of charge and discharge rate, cycle life and energy densities,” said Shen Dillon, a collaborator on the project led by Jennifer Lewis. “We’re just able to achieve this on a much smaller scale.”

Lewis, currently a professor at Harvard, led the project while at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in collaboration with Dillon. They have published their results in the journal Advanced Materials. 3D printing (or additive manufacturing), once used mainly for prototyping circuit boards and other electronics, has exploded in the last few years, being used for everything from aircraft to flexible displays and, famously, guns. The Army 3D prints gear for troops in on the spot in Afghanistan. NASA wants to 3D print food on long space missions. And the Obama administration has touted it as the future of manufacturing.

Its possibilities are only likely to grow. Prices for 3D printers are coming down, making them available to innovators with any kind of budget. One engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is even pushing into 4D, researching how to print objects that change over time.

While many 3D printing projects are going big — even to the point of planning to print an entire house — taking it to the nanoscale could have an even bigger impact. With the Harvard/UI team’s tiny batteries on board, the possibilities for microscopic implants, sensors, cameras, wearable computers and other gear just grew.