Using tech to open the legislative sausage factory

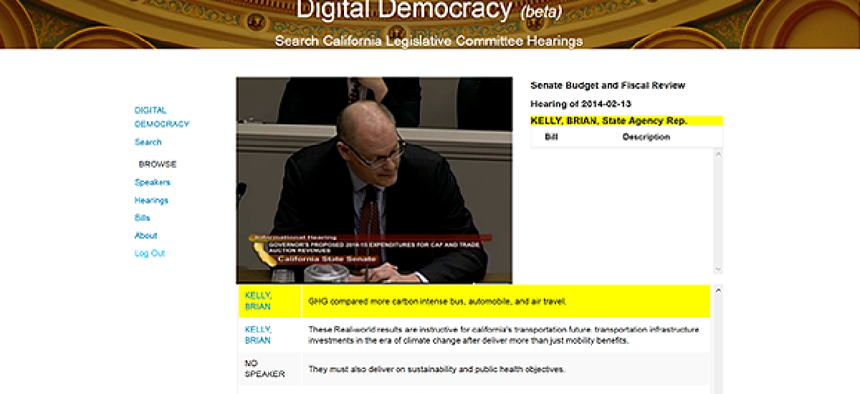

The Digital Democracy site will not only feature a searchable video database of state legislative committee meetings and hearings but transcripts of what was said.

Want to keep tabs on what your legislature is doing about funding bus transportation or implementing a carbon tax but you can’t afford to hire someone to go to committee hearings? If you’re in California, you’re in luck. Or at least you will be soon.

A team at the Institute for Advanced Technology & Public Policy at California Polytechnic State University is developing Digital Democracy, a searchable video database of state legislative committee meetings and hearings. But what makes Digital Democracy special is that it offers not only video clips but transcripts of what was said.

When you enter search terms, Digital Democracy returns a list of videos with matching terms. Select a video and it will be displayed for playback. As you play the video, the transcript is displayed below.

Digital Democracy is the brainchild of former California State Sen. Sam Blakeslee. After serving eight years in the legislature, Blakeslee founded the institute in 2012 and was intent on finding ways to shed more light on the workings of the state legislature.

“I experienced firsthand how important it was to be able to know exactly who had said what, when during the process of amending or debating a bill,” Blakeslee said. “And in California, because there is no system whereby transcripts or notes of any kind are made of those lively debates, everyone largely depended upon their memory or their assertions. That ended up being highly problematic.”

Having an easy-to-access record of proceedings, Blakeslee figured, would not only be a good reference source, it would change the behavior of legislators and lobbyists. “What I saw firsthand was that many lobbyists and legislators acted as if no one really heard or saw what they said or how they behaved,” Blakeslee said. “I found that shocking. Committee hearings would be filled with scores of lobbyists and not a single member of the public and not a single journalist. I really felt the people would have behaved more professionally if they knew people were watching.”

Digitial Democracy, which is still in beta, currently relies on a combination of natural language processing and human editors to generate the transcripts of meetings.

According to Foaad Khosmood, senior fellow at the institute and professor of computer engineering at Cal Poly, the team is working to improve the natural language processing engine to reduce the amount of time required from human editors.

“The state of the art on these things is that they are really not that good,” Khosmood said. “You can have your off-the-shelf commercial text-to-speech technologies, and they will not really do any kind of professional job on a domain like politics because they just don’t know all of the phrases.”

Currently, about four hours of human editing is required to generate one hour of accurate transcript. The team expects improvements in their language-processing technologies to improve that ratio to one hour of human editing for one hour of transcript within the next year.

The system is employing a Microsoft language-processing engine, though according to Khosmood, it’s not the one that ships in Windows. “The service that we are trying is geared toward bigger businesses is not very public,” he said. And, indeed, Microsoft has declined to respond to inquiries about the service.

The Digital Democracy team is also developing software to analyze the initial transcriptions to make corrections. And the researchers are looking to integrate other technologies, including facial recognition, to improve the accuracy and usefulness of the archive.

“The goal is to evolve technology to the point where human involvement declines rapidly using techniques like facial recognition,” Blakeslee said. “By training the system to identify faces, we can shave off a significant amount of time that it currently takes to make sure that the right person is identified as the speaker.”

And correct identification of speakers opens up possibilities for further data integration. “We want to allow people to be able to search on who said what, but also we are linking to other databases that have information about who that person is,” Blakeslee said. Information on lobbyists, for example, is available in companion data sets that are maintained by the secretary of state, he said

In addition to allowing users to distribute videos and transcripts via social media, Blakeslee said his team is looking for ways to most effectively integrate input from users.

Of course, as Blakeslee acknowledged, allowing user input also creates challenges for ensuring the accuracy of such input.

As Digital Democracy’s language-processing capabilities and its interface further develop, the institute is also searching for funding to take the project live. Assuming such funding is secured, Blakeslee said he expects the platform to be online and available to the public by July 2015.

NEXT STORY: Making UAVs more maneuverable