Seeing through walls with Wi-Fi

Despite the low energy of Wi-Fi signals, they can be used to effectively penetrate concrete to detect human movement and to map spaces and objects inside buildings.

Wi-Fi -- long disparaged as networking technology that too often drops signals due to interference or to its relatively short range -- is showing surprising potential as an imaging technology that may help first responders see through walls.

While no products have as yet reached market, work in research labs around the country are showing that despite the low energy of Wi-Fi signals, they can be used to effectively penetrate concrete to detect human movement and to map spaces and objects inside buildings. Thanks to increasingly sophisticated algorithms for detecting and measuring Wi-Fi signals and filtering out distortions, Wi-Fi may soon be deployed on robots to search collapsed buildings for survivors or in homes to monitor the health of the occupants.

A team at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab has been focused on using Wi-Fi to track human movements. In principle, the system works like radar and sonar, with a device emitting Wi-Fi signals in the 2.4 gigahertz band and then detecting as the signals are reflected by objects.

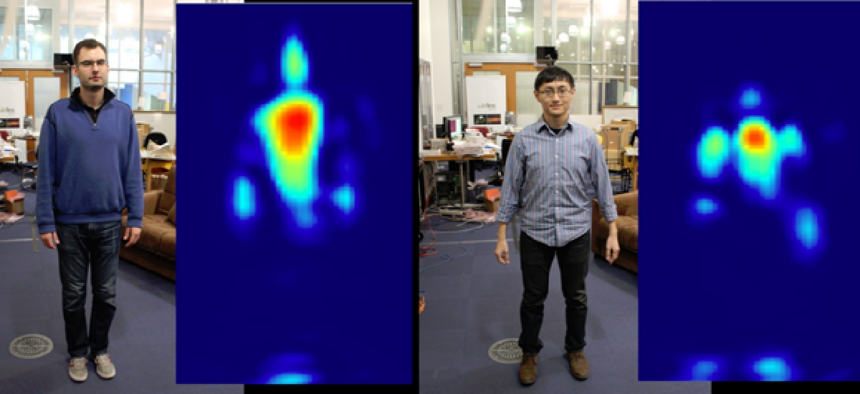

The system -- named RF-Capture -- employs a custom-built Wi-Fi transmitter and antenna array that is about the size of a microwave oven. In addition to being larger than commercial Wi-Fi routers, RF-Capture sends signals in the 5.46-7.24 GHz range. RF-Capture then uses algorithms designed to select for human forms that move through space when it takes its “snapshots.”

According to the team’s paper -- delivered at a conference in November -- the system can trace a person’s hand as he writes in the air, and it can distinguish between 15 different people with an accuracy rate of nearly 90 percent.

RF-Capture doesn’t, however, deliver even poor video-quality images. Instead, the heavy lifting has to be done by the algorithms. In fact, moving human bodies reflect signals in different directions, so only a partial reflection makes it back to the antenna array. In earlier system that used radar, the authors noted, this problem could only be solved using a very large antenna array. RF-Capture keeps the array small by doing the analysis in software.

The researchers acknowledge that RF-Capture has significant limitations. Most notably, the current version assumes that the subject is walking toward the device. “We believe these limitations can be addressed as our understanding of wireless reflections in the context of computer graphics and vision evolves,” they wrote.

Perhaps more significantly, the accuracy of the device drops off quickly as the distance to the subject increases. While it can correctly identify body parts with 99.13 percent accuracy when the subject is 3 meters away, RF-Capture is only 76.4 percent accurate when the subject is 8 meters away.

Still, the authors see a grab bag of potential uses -- from gaming to emergency response. In fact, the team is currently building a product for those caring for the elderly that can detect and report falls.

A team at the University of California at Santa Barbara is taking a different approach that may be of more immediate help to first responders because it is mobile by design.

The UCSB team sent out two P3-AT robots -- four-wheeled platforms that are about 20 inches long and 19 inches wide -- equipped with Wi-Fi transmitters and directional antennas. One of the robots also has an off-the-shelf D-Link WBR-1310 wireless router attached to its antenna, which it uses to send a constant wireless signal for the other robot in order to measure signal strengths.

As the robots separately move around the structure being explored, they transmit and send Wi-Fi signals to each other and analyze the difference between sent and received signal strengths to generate a map of the objects inside the walls. Unlike the MIT team’s solution, the UCSB robots aren’t focused just on detecting human forms. The maps generated include all objects in the space, with a target resolution of only 2 centimeters.

Not surprisingly, given that it is still in the research phase, the as-yet-unnamed UCSB robotic Wi-Fi system also has some significant limitations.

To begin with, the robots do not at this point transmit their maps to an operator in real time. Instead, the measurements are stored on each robot and are transferred to a remote PC after the mission is complete. That could be critical lost time in an emergency situation.

The operator of the robots also has very limited control over their activities. While the operator can intervene in an emergency to redirect the robots, the system depends on the two robots following predefined paths at a set speed to take measurements and ensure they can send signals to each other. Any changes in position would result in misaligned antennas.

Finally, the speed of the robots is currently limited to 10 centimeters per second, not exactly warp speed when lives are on the line.

Fortunately, there’s no reason to think that all of these limitations can’t be removed through further development.

Reliable Wi-Fi that reaches both my home office and my den without losing connections, however, may be a different story...

Editor's note: This blog was changed Nov 18 to correct the frequency of the Wi-Fi signals from 2.4 kilohertz to 2.4 gigahertz.

NEXT STORY: Paving the way for flexible electronics