Passive Wi-Fi will boost Internet of Things

Connecting state and local government leaders

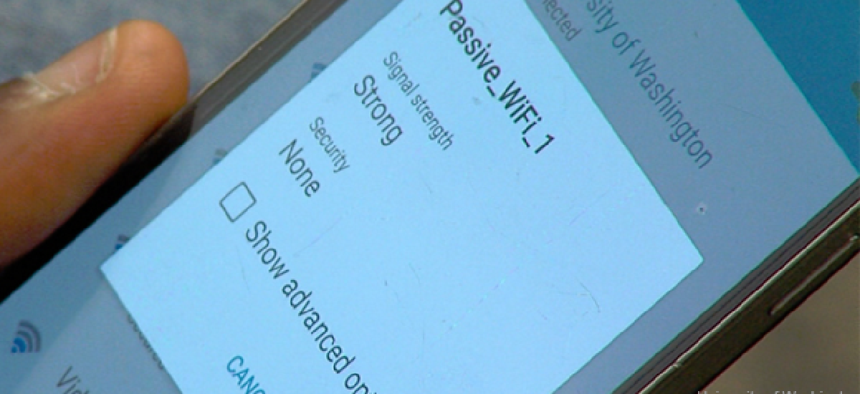

Researchers at the University of Washington have developed a way that passive, or reflected, signals can help IoT sensors transmit data while using far less power than existing Wi-Fi devices.

One of the critical obstacles to achieving an efficient Internet of Things is being able to build sensors small enough to be implanted in all the nooks and crannies of our environment but that still carry enough power to send their data. Until this problem is solved, sensors can't be widely deployed if their batteries need changing every few months.

Researchers at the University of Washington have taken a major step forward in addressing that challenge. They've radically improved IoT sensor efficiency by developing “passive Wi-Fi” systems that require 10,000 times less power than existing Wi-Fi devices and 1,000 times less power than shorter-range technologies such as Bluetooth and Zigbee.

According to Vamsi Talla, a doctoral student in electrical engineering at the University of Washington and a member of the passive Wi-Fi research team, the trick is that instead of using power-consuming analog radio signals to send data among sensors and receivers, passive Wi-Fi reflects radio signals from a traditional, plugged-in router, sending Wi-Fi signal packets to devices, like sensors or smartphones, that can decode the signals.

“A good analog is a flashlight,” Talla said. “If you want to transmit using a flashlight you turn the flashlight on and off. But that takes a lot of power.” The team at UW took a different approach. According to Talla, the strategy was, “Let’s not actually generate our own light but just reflect it.”

In fact, the team had been working on what are known as “backscatter” technologies for the past two to three years. “But the cool thing here,” Talla said, “was that we figured out how we can use that concept to generate actual Wi-Fi.”

According to Talla, the power in the UW’s passive Wi-Fi system is provided by a device plugged into a wall outlet. With that device sending out RF signals, passive sensors within 100 feet can use their low-power digital switches to reflect or absorb those signals.

While the low-power sensors still require batteries, they consume so little power that the batteries shouldn’t need to be replaced. “The sensor should last the lifetime of the battery, which is 10 to 12 years,” Talla said.

According to Talla, the UW team spun off a company six months ago to develop the technology into commercial products. Talla declined to go into detail, but said that Jeeva Wireless, based in Seattle, is currently seeking investors. The company also has gotten a number of inquiries from firms developing and marketing home automation systems, according to Talla.

At the same time, Jeeva Wireless is not focusing on specific IoT markets. “We don’t feel like we have to focus on vertical markets,” Talla said, “since we feel we can impact all areas where Wi-Fi or IoT devices exist.”

NEXT STORY: FAA tests drone detection system