Dipsticking aquifers from space

Orbiting satellites can measure the "breathing" of the earth as water is added to or drawn from underground aquifers.

As climate change is expected to cause increasing numbers of severe droughts, policymakers and water managers are looking for any edge. Researchers at the University of Buffalo have found a way to monitor groundwater by using satellites to measure the “breathing” of the earth as water is added to or drawn from underground aquifers.

Specifically, the researchers use InSAR -- interferometric synthetic aperture radar -- beamed from orbiting satellites to measure the distance between the satellite and the surface below. InSAR’s 3.1-centimeter wavelength and 9.6-GHz frequency allow the waves to pierce through cloud cover without distortion, bounce off the ground and return directly to the satellite sensors. What’s more, the radar is accurate enough to detect changes in ground level as small as a millimeter.

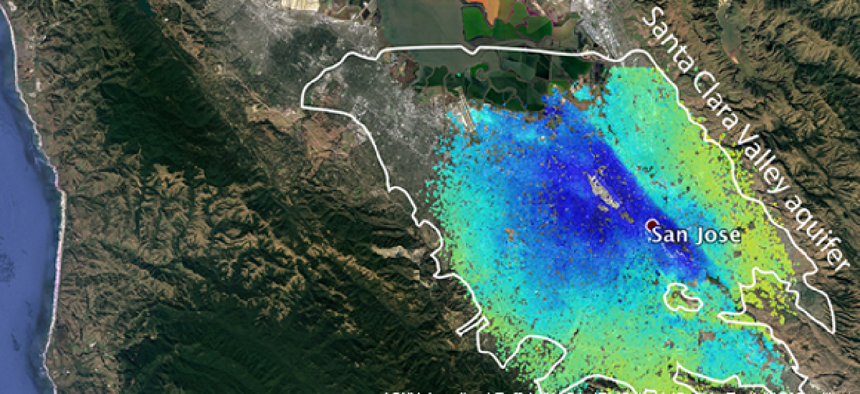

To test the technology, geologist Estelle Chaussard and her team first calibrated it by comparing it to readings from the Santa Clara Valley Water District in California, which has historical manual readings from 215 wells, as well as readings from sensors buried 300 meters below ground.

According to Chaussard, the InSAR data showed ground levels in the water district regularly moving approximately three centimeters up and down over a year, as a result of the ground subsiding when water is extracted and evaporates over the summer and is replenished from precipitation during the winter. The readings “match actually very well” to those from the water district’s wells, she said.

The study, which took place during the 2012-2015 drought that afflicted the region, also found drought-induced changes in ground levels as large as 15 centimeters.

While measurements accurate at that scale require calibrating the radar readings with on-the-ground readings of specific aquifers, after that calibration, the InSAR system can be used to accurately update data on the aquifer levels without the need to maintain sensors in areas that are in many cases very difficult to access.

“What we are trying to do more and more now is to try and use this data together with well data to fill in the gaps,” Chaussard said. “Even where we have well data, we are not going to have the same spatial coverages as we can get with InSAR.”

Just as important to water managers, the turnaround time for InSAR satellite data can be as quick as 24 hours, assuming the space agencies cooperate. For their study, Chaussard said it took a couple of months to get the data, but depending on agreements with the space agencies it can be obtained as soon as the next day.

That kind of quick feedback can be important during droughts. According to Chaussard, the team was able to detect improvements in the Santa Clara aquifer in 2014, a year before rains returned. “The recovery was directly related to the efforts of the water district in conserving water,” Chaussard said.

NEXT STORY: FAA pushed to protect airspace from rogue drones