What Cities Need to Know About Chatbots and Data Security

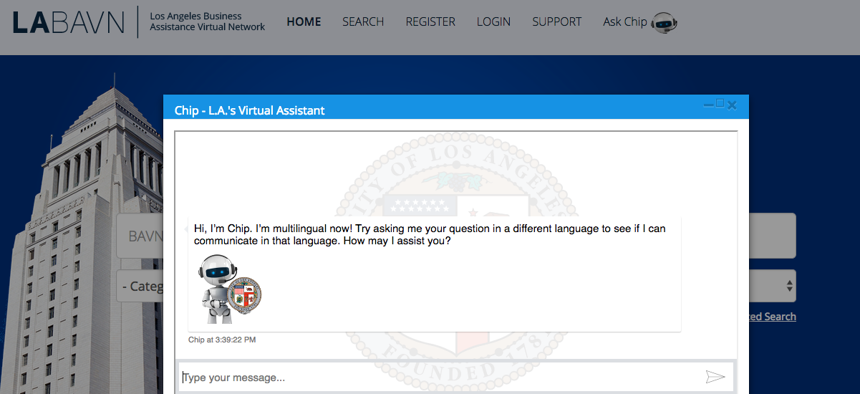

Meet Chip, a city chatbot in Los Angeles City of Los Angeles

Chatbots make city services more efficient, but are they safe to use?

Want to sell to the city of Los Angeles? Then talk to Chip. Short for City Hall Internet Personality, it’s a website-based chatbot answering questions about the local procurement process. In Kansas City, Missouri, Facebook Messenger bot Open Data KC answers open records requests. And if you see a pothole or a broken street light in North Charleston, South Carolina or Williamsburg, Virginia, text Citibot. It processes traffic light outages and new street sign requests, too.

Across multiple areas of service, chatbots are slowly but surely helping governments become more efficient. During the first six months of Citibot use, North Charleston filled 76-percent more potholes and fixed 195- percent more traffic and street lights than usual. Sounds great, but there’s one problem—not for North Charleston per se, but for governments everywhere: Are chatbots safe?

They certainly seem innocuous, alone in their little box on the side of a website or innocently connecting to Slack. But because of how governments and enterprises buy bots, Rob May, CEO of chatbot startup Talla, said we’re heading toward a data security crisis: “In the early days of [software-as- a-service] SaaS,” he explained at a user conference, “it was sold as ‘Hey, marketing department, guess what? IT doesn’t have to sign off, you just need a web browser’ and IT thought that was fine until one day your whole company was SaaS.”

One purchase here and another there, until organizations were permeated by software bought without any data management best practices in place. That’s why May recommends chatbot customers streamline purchasing and security now.

Unlike the private sector, which gives employees more freedom in what they can download, governments typically have firewalls blocking staff from installing unapproved software. But the hacking concern here isn’t protecting employees’ computers. It’s constituent data. If a business owner gives Chip her company’s employer identification number, how securely is it stored? Could addresses for all those reported potholes be used to triangulate where somebody lives? Even approved chatbots pose security risks if unprotected. So what steps should cities take to keep the data they process safe?

First, May suggests, identify what you’re working with: Is it personally identifiable information? In North Charleston, for example, spokesperson Ryan Johnson said Citibot only stores phone numbers—in case the city has a question. But Mrs. Landingham, a U.S. General Services Administration Slackbot, has a much wider scope: GSA uses the bot to onboard new hires, so it takes employees’ biographical information. Obviously, the more sensitive the data, the stiffer the protection.

When determining data sensitivity, don’t just look at the information the chatbot is supposed to collect. Look at what it could. Take a health department bot, for example, designed to tell people when different locations are open. “What are you hours?” is what the system expects. “My name’s Susan and I need to know when you do STD tests” may be what it gets.

“If you think about conversational interactions with bots, we’re naturally going to be giving up more information than we intend to,” said Jim O’Neill, chief product officer for cybersecurity company IBOSS. “Humans will volunteer data.” Your hours don’t need high-level security, but that extra info people enter does.

Next, May suggests determining “who has the right to install a bot and why.” Is the health department even allowed to choose its own bot, or is all purchasing centralized through procurement and IT? Some chatbots are free, so does procurement still need to be involved? If they aren’t, which department owns oversight?

Consider implementing a single, citywide policy, one May said should address “the kind of certifications [vendors] have.” His chatbot, Talla, is a lot like GSA’s Mrs. Landingham: It answers HR questions—meaning lots of personal identifiable information.

May said, “Some of the things that set [chatbots] apart are if we have or are pursuing SSAE 16 [or] SOC 2” security compliance certifications. “You want to think about data encryptions, keys,” and working security expectations into your service level agreements, he added. These SLA’s should outline what happens if agreement terms aren’t met, as well as how the bot maker identifies and manages information risks.

Finally, May said, don’t forget data derivatives: “What can [the chatbot company] do with your data? Can I package up all these questions once I have a million of them and sell them as some kind of other product?” Post-Cambridge Analytica, ‘who owns the data’ is a question government can’t afford to not ask. As Mark Zuckerberg’s recent congressional hearings show, government, startup, and citizenry expectations of data ownership vary.

Whatever you do, though, don’t let the risks discourage you. As North Charleston proves, chatbots bring real value to cities and the people they serve. Johnson reported a 112-percent uptick in public works efficiency thanks to Citibot. “There’s a tradeoff,” May said. “Sometimes [the chatbot] might be the only way to get done what you need done.” In that instance, he said, “You have to decide, can your data go out there?”

Terena Bell is a journalist based in New York.

NEXT STORY: Salt Lake City, NYC land wireless testbed pilot