How the 'mother of all demos' changed the world

In 1968, computers got personal as Douglas Engelbart made people re-think what computers can do.

This article was first posted on The Conversation.

On a crisp California afternoon in early December 1968, a square-jawed, mild-mannered Stanford researcher named Douglas Engelbart took the stage at San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium and proceeded to blow everyone’s mind about what computers could do. Sitting down at a keyboard, this computer-age Clark Kent calmly showed a rapt audience of computer engineers how the devices they built could be utterly different kinds of machines – ones that were “alive for you all day,” as he put it, immediately responsive to your input, and which didn’t require users to know programming languages in order to operate.

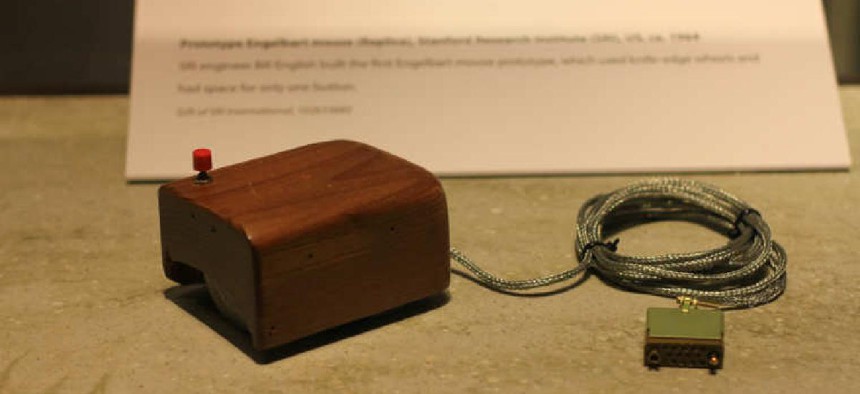

Engelbart typed simple commands. He edited a grocery list. As he worked, he skipped the computer cursor across the screen using a strange wooden box that fit snugly under his palm. With small wheels underneath and a cord dangling from its rear, Engelbart dubbed it a “mouse.”

The 90-minute presentation went down in Silicon Valley history as the “mother of all demos,” for it previewed a world of personal and online computing utterly different from 1968’s status quo. It wasn’t just the technology that was revelatory; it was the notion that a computer could be something a non-specialist individual user could control from their own desk.

The first part of the ‘mother of all demos.’

Shrinking the massive machines

In the America of 1968, computers weren’t at all personal. They were refrigerator-sized behemoths that hummed and blinked, calculating everything from consumer habits to missile trajectories, cloistered deep within corporate offices, government agencies and university labs. Their secrets were accessible only via punch card and teletype terminals.

The Vietnam-era counterculture already had made mainframe computers into ominous symbols of a soul-crushing Establishment. Four years before, the student protesters of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement had pinned signs to their chests that bore a riff on the prim warning that appeared on every IBM punch card: “I am a UC student. Please don’t bend, fold, spindle or mutilate me.”

Earlier in 1968, Stanley Kubrick’s trippy “2001: A Space Odyssey” mined moviegoers’ anxieties about computers run amok with the tale of a malevolent mainframe that seized control of a spaceship from its human astronauts.

Voices rang out on Capitol Hill about the uses and abuses of electronic data-gathering, too. Missouri Senator Ed Long regularly delivered floor speeches he called “Big Brother updates.” North Carolina Senator Sam Ervin declared that mainframe power posed a threat to the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. “The computer,” Ervin warned darkly, “never forgets.” As the Johnson administration unveiled plans to centralize government data in a single, centralized national database, New Jersey Congressman Cornelius Gallagher declared that it was just another grim step toward scientific thinking taking over modern life, “leaving as an end result a stack of computer cards where once were human beings.”

The zeitgeist of 1968 helps explain why Engelbart’s demo so quickly became a touchstone and inspiration for a new, enduring definition of technological empowerment. Here was a computer that didn’t override human intelligence or stomp out individuality, but instead could, as Engelbart put it, “augment human intellect.”

While Engelbart’s vision of how these tools might be used was rather conventionally corporate – a computer on every office desk and a mouse in every worker’s palm – his overarching notion of an individualized computer environment hit exactly the right note for the anti-Establishment technologists coming of age in 1968, who wanted to make technology personal and information free.

The second part of the ‘mother of all demos.’

Over the next decade, technologists from this new generation would turn what Engelbart called his “wild dream” into a mass-market reality – and profoundly transform Americans’ relationship to computer technology.

Government involvement

In the decade after the demo, the crisis of Watergate and revelations of CIA and FBI snooping further seeded distrust in America’s political leadership and in the ability of large government bureaucracies to be responsible stewards of personal information. Economic uncertainty and an antiwar mood slashed public spending on high-tech research and development – the same money that once had paid for so many of those mainframe computers and for training engineers to program them.

Enabled by the miniaturizing technology of the microprocessor, the size and price of computers plummeted, turning them into affordable and soon indispensable tools for work and play. By the 1980s and 1990s, instead of being seen as machines made and controlled by government, computers had become ultimate expressions of free-market capitalism, hailed by business and political leaders alike as examples of what was possible when government got out of the way and let innovation bloom.

There lies the great irony in this pivotal turn in American high-tech history. For even though “the mother of all demos” provided inspiration for a personal, entrepreneurial, government-is-dangerous-and-small-is-beautiful computing era, Doug Engelbart’s audacious vision would never have made it to keyboard and mouse without government research funding in the first place.

Engelbart was keenly aware of this, flashing credits up on the screen at the presentation’s start listing those who funded his research team: the Defense Department’s Advanced Projects Research Agency, later known as DARPA; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; the U.S. Air Force. Only the public sector had the deep pockets, the patience and the tolerance for blue-sky ideas without any immediate commercial application.

Although government funding played a less visible role in the high-tech story after 1968, it continued to function as critical seed capital for next-generation ideas. Marc Andreessen and his fellow graduate students developed their groundbreaking web browser in a government-funded university laboratory. DARPA and NASA money helped fund the graduate research project that Sergey Brin and Larry Page would later commercialize as Google. Driverless car technology got a jump-start after a government-sponsored competition; so has nanotechnology, green tech and more. Government hasn’t gotten out of Silicon Valley’s way; it remained there all along, quietly funding the next generation of boundary-pushing technology.

The third part of the ‘mother of all demos.’

Today, public debate rages once again on Capitol Hill about computer-aided invasions of privacy. Hollywood spins apocalyptic tales of technology run amok. Americans spend days staring into screens, tracked by the smartphones in our pockets, hooked on social media. Technology companies are among the biggest and richest in the world. It’s a long way from Engelbart’s humble grocery list.

But perhaps the current moment of high-tech angst can once again gain inspiration from the mother of all demos. Later in life, Engelbart described his life’s work as a quest to “help humanity cope better with complexity and urgency.” His solution was a computer that was remarkably different from the others of that era, one that was humane and personal, that augmented human capability rather than boxing it in. And he was able to bring this vision to life because government agencies funded his work.

Now it’s time for another mind-blowing demo of the possible future, one that moves beyond the current adversarial moment between big government and Big Tech. It could inspire people to enlist public and private resources and minds in crafting the next audacious vision for our digital future.