Library of Congress checks out 3D printing

A LOC working group is learning to use 3D photogrammetry to build digital models of artifacts held in the Library’s collections.

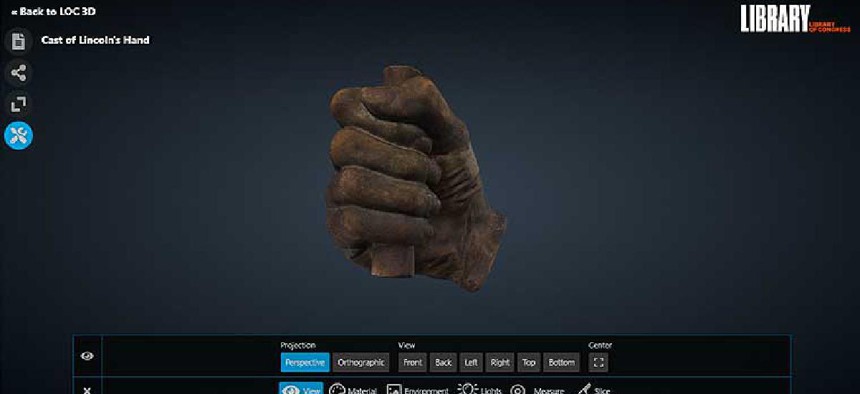

Have you ever wished you could fist bump President Abraham Lincoln? Now you can -- well, after you make a print of the 3D image that the Library of Congress recently posted.

The larger-than-life hand (clutching a sawed-off broomstick handle) of a larger-than-life president is one of two 3D images that the library’s 3D Digital Modeling, Imaging and Printing Working Group has posted so far in the Experiments Gallery of the library’s LC Labs website. The other is of an exposicio mistica super exod[um], a 12th-century manuscript on vellum, parchment made from calf skin.

Website visitors can twist and turn the images to see them from every angle, manipulate them to see what they look like in other materials such as clay, with other backgrounds, in different light, measure them with the tape tool and slice them into smaller parts. They are also read details about the artifacts and download STL files for 3D printing.

To create the images, the working group learned from Cultural Heritage Imaging, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the digital capture and documentation of artifacts, to use photogrammetry, a process that uses software to create web-viewable 3D models from images. It involves using a DLSR camera much like a landscape photographer would use.

“The difference is when they’re capturing objects using 3D photogrammetry, the photographer takes a series of photos of the objects from a wide number of angles,” said Stephen Wesson, chairman of the working group. “It’s just an object having its portrait taken dozens and dozens of times, hundreds of times.”

The images are uploaded from the camera to a computer, where commercial software stitches the images together to create the 3D model. All of the data is stored on the library’s servers, Wesson said, adding that it takes about an hour to photograph an object and almost 10 times that to stitch together all the images.

The Smithsonian Institution’s Digitization Program Office implemented its Voyager open source web viewer so that the LC Labs team could showcase the 3D models online. Developed in 2018, Voyager is a 3D viewing, authoring and publishing tool supporting the Smithsonian’s mission to preserve, process and publish 3D content.

The idea for the digitization of artifacts came about when library officials recognized an interest in working with 3D objects among teachers and community and school librarians.

The pilot project that produced the two images launched last fall with 13 staff members from across the library’s offices to get a range of perspectives on what to digitize, said Wesson, an educational resource specialist at the library.

The team’s first step was researching which audiences would be interested in 3D images and how other cultural institutions handle their 3D initiatives.

“A central priority of the library is to ensure that all Americans are connected to the library,” Wesson said. “In everything we undertake, we try to be aware of our public, our many different audiences and how useful they might find the materials we’re making available.”

In education, for example, students could use digital 3D models to better understand an object’s structure and curate their own 3D collections for projects. Most importantly, the images can be a jumping off point for social learning, Wesson said.

“When something is sitting on the table in front of you, you’re more likely to look at it from many different sides, you’re more likely to spend more time with it than if you were just staring at it on a screen,” he said.

Next, the group put out a call to library offices for suggestions of artifacts for 3D digitization. The short list included Charles Dickens’ walking stick, writer James Joyce’s death mask, stamps that were used to create early editions of Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” poetry collection, a mechanical box that performs magic tricks with cards, the seal of King Charles I of England, bullets and objects made of hair -- which was often woven into keepsakes in the 19th century or included in a person’s effects after they died.

Ultimately, some suggestions didn’t pan out.

“There are objects that don’t work well with 3D digitization because they’re too shiny, some because they’re too complex,” Wesson said. “We had to eliminate some for rights purposes. It turns out that the death mask of James Joyce is under copyright. We wanted to make sure that everything we publish was rights-free so that teachers and anyone could use them and reuse them.”

Next in line for 3D digitization is a banjo from the early 20th century with carved wood and signatures from legendary musicians such as Woody Guthrie. The working group will promote the 3D objects online and in person at the Thomas Jefferson Building to better understand how people use them. In June, Wesson expects to submit a report on the project to library leaders, who will determine whether 3D digitization becomes a sustained effort.