What transportation officials need to consider when using AI

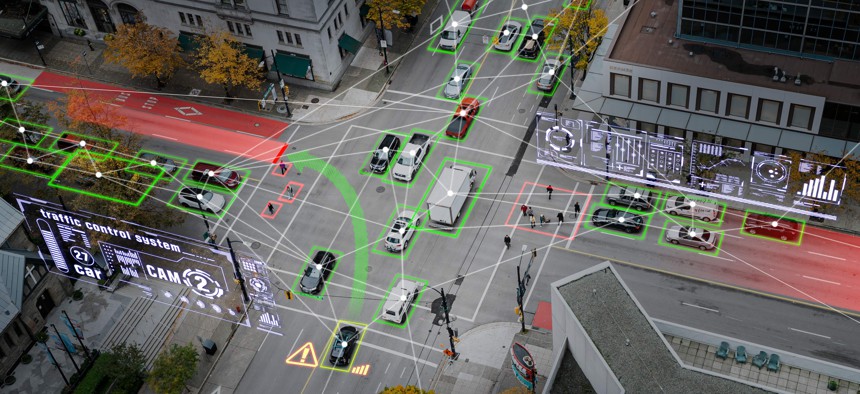

choi dongsu via Getty Images

Artificial intelligence tools are proliferating in transportation. Two tech experts offer advice on how to approach the emerging technology.

Artificial intelligence is slowly getting a foothold in transportation, with applications ranging from driverless cars to protecting pedestrians at dark crossings to rerouting buses to where demand is greatest.

But the emerging technology has also contributed to major transportation failures, such as when a school district in Louisville, Kentucky, relied on an AI tool to help redesign its bus routes. Some students never made it to school in the morning, and others didn’t get home until after 10 p.m. The school district canceled classes for a week to fix the problem.

So how should transportation officials handle the proliferation of new AI tools? The Eno Center for Transportation, a think tank, recently asked two tech experts to offer advice for how best to roll out the technology. Here are a few of their suggestions.

Be clear where responsibility lies. Renee Autumn Ray, the senior director of transportation policy at Hayden AI and the author of an Eno report on AI in transportation, said people in government often look at new tech tools as a way to solve existing problems. “It’s very important that we still understand that people are accountable for the work that gets done,” she said. “And when you’re thinking about artificial intelligence, it should be a tool, but the decision should still rest with the practitioner or the policymaker, who is implementing the tool.”

Regulate carefully. The U.S. does not currently regulate artificial intelligence. In fact, even defining what AI is can be tricky. Experts tend to agree that it has two prominent features: It is autonomous, which means it can work without human intervention, and it shows adaptivity, or the ability to “learn” from previous experience to improve its output.

Sameer Sharma, a former Intel executive and a member of Eno’s board of advisors, said governments should focus on regulating how AI is rolled out, rather than the technology itself. The first step is to make sure that data used by those systems is protected, collected in an acceptable way, audited, corrected when necessary and reflects the population it serves.

From there, the government can play a large role in establishing standards for how AI can be deployed, Sharma said, and what is considered safe and not safe. If public officials leave that process up to the private sector, he said, “we will still get there but the road will be winding a lot, and it will be accident-prone along the way.”

Public agencies can also play a role in making sure that AI systems are interoperable, Sharma said, so tools can work together.

Look for ways to use AI to recover from cyberattacks. The rollout of connected systems in transportation networks opens the door for outside attacks that would never have been feasible in the days of concrete, steel and physical switches, Sharma said. The proliferation of AI could make it easier for bad actors to take control of those systems.

But AI could also help agencies that fall victim to network attacks recover. “Suppose there’s a traffic intersection and somebody decides to mess with it and make all the lights red or green just to create confusion and chaos,” Sharma said. “A backup system could say, ‘Look, we are detecting something weird happening, we are going to shut down connectivity to the cloud. We’re going to default to a very conservative behavior, even if it is not efficient.’”

Limit the amount of data that is shared. Ray said one practice that could limit the malicious use of artificial intelligence is to be picky about what kinds of data an agency stores. For example, a vehicle with a traffic camera on board only needs to upload the video of vehicles that are speeding to the cloud, rather than sharing a full day’s worth of material.

Expect AI to roll out gradually and then suddenly. Sharma cautioned that people should think of current AI tools as “augmented intelligence” rather than “artificial intelligence” for the foreseeable future. It will be something that helps people do their work more efficiently, or helps them drive more safely.

But with most major tech innovations, the public gets hyped about the possibilities early on, but the rollout comes slower than many of them would have thought, Sharma said. That said, once the technology does take root, “the impact has been larger and broader than we thought,” he said. “We could not imagine those possibilities.”

Finally, the technology tends to spread after hitting an economic inflection point that makes it more feasible to deploy. That’s why autonomous vehicles haven’t become widely available, he said. Robotaxis can cost half a million dollars, which is far out of reach for people used to paying $20,000 to $80,000 for a car, he said.

“For everybody fearing AI, my recommendation is to take a deep breath,” he said. “Look how resilient we’ve been in absorbing these big transitions.”

Daniel C. Vock is a senior reporter for Route Fifty based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: What is artificial intelligence? Legislators are still looking for a definition.