Taxing by the Mile, Not the Gallon

JPL Designs / Shutterstock.com

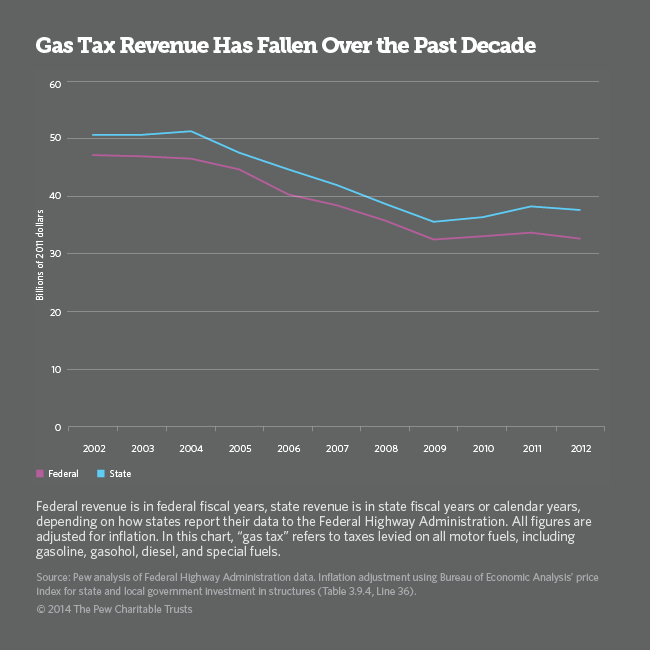

The traditional gas tax isn’t generating enough money for roads and bridges. Could a “road usage tax” replace it?

This story originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

SALEM, Oregon—Evan Burroughs plopped into his 1996 Subaru Outback and pointed to a green plastic box tucked below the steering column. It blinked once. As Burroughs eased the car out of the parking lot and drove toward the highway, the box kept track of his speed and braking, but most importantly, of how many miles he drove.

The green box, part of a pilot program, sends the data to a private contractor like a GPS device manufacturer, which reports the miles to Oregon, which calculates Burroughs’ tax bill—1.5 cents per mile.

As revenue from the standard per gallon gas tax diminishes, states are looking for other ways to pay for the construction and maintenance of roads and bridges. California recently authorized its own mileage tax pilot project. Between 2008 and 2014, at least 19 states considered 55 measures related to mileage-based fees, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Vermont and Washington enacted bills to study per-mile fees in 2012.

But Oregon is leading the way. Its experiment, OreGO, is the first that involves ordinary citizens. Other states have been watching closely since the program began July 1.

“It’s kind of like playing a computer game, but with real stuff,” said Burroughs, 56, who obviously gets a kick out of seeing data detailing his driving habits.

Matthew Garrett, Oregon’s transportation director, noted that Oregon enacted the nation’s first gas tax in 1919 so it could pay for roads to get vehicles out of the mud. “We’ve always been pioneers, and after 90 years, it’s time to innovate again,” he said.

Diminishing Returns

New, more fuel efficient cars have eaten into gas tax revenue. Furthermore, many gas tax rates—including Oregon’s 30-cent levy—have not kept up with inflation. In Oregon the effective tax rate will fall to less than 24 cents per gallon in inflation-adjusted terms within 10 years, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a nonpartisan think tank. That decline would basically undo the state’s 6-cent increase in 2009, ITEP noted.

A mileage, or road usage, tax also erodes with inflation, but is immune from improvements in fuel efficiency.

“If you don’t have the revenue source you can’t maintain the infrastructure,” Garrett said. “Traditional methods of funding transportation—the gas tax—were constructed for the longest time. But the world has changed.”

For purposes of the experiment, which isn’t designed to put more money in the state’s coffers, Oregon charges 1.5 cents for every mile driven. Every driver who participates in the program, whether he or she drives a little fuel-efficient car or a big pickup truck, pays the same rate for driving on Oregon roads (the program doesn’t count driving in other states or on private roads). The state reimburses drivers who paid more in traditional gas tax than they would be assessed using the mileage calculation.

To illustrate how the program works, the Oregon Department of Transportation compared a 2014 Toyota Prius and a 2014 Ford F-150 (the two most popular vehicles enrolled in the program). The Prius averages 50 mpg and the F-150 gets 18 mpg. The average Oregonian drives 12,962 miles a year.

Given those numbers, the Prius owner would use 259 gallons in a year and pay $77.77 in gas taxes, while the F-150 owner would use 720 gallons and pay $216 in gas taxes. The annual road usage tax due for both drivers would be $194.43.

The average Prius owner would pay the state $116.66 (the difference between the $194.43 in road usage taxes and the $77.70 in gas taxes), while the average F-150 owner would get a $21.60 rebate (the difference between the $216.03 in gas taxes and the $194.43 in road usage taxes).

Garrett said the goal isn’t to discourage the use of fuel-efficient cars, but rather to ensure that those drivers are paying their fair share to maintain roads and bridges, which they rely on just as much as drivers of less fuel-efficient cars.

“On a fundamental level, having people pay for the roads by how much they use them is fair,” said Jessica Moskovitz, of the Oregon Environmental Council. But she urged the Legislature, when it evaluates the program, to think twice about “incentivizing cars that are good for our planet or incentivizing gas guzzlers.”

Nel Osborn, 64, a Salem retiree who drives a Prius with a “53 MPG” license plate, volunteered for the experiment. She pays an additional $1 to $1.50 to the state per month under the road usage tax system. “It does seem weird that people who have Hummers benefit and people that drive Priuses do not,” she said. But Osborn said she is willing to pay a little more to help maintain Oregon’s roads and bridges. The extra money she owes is deducted automatically from her account, and she said the additional information had changed her driving habits: “I’ve been braking a little less.”

The trial program is also designed to gauge what people think about the new system, and both Osborn and Burroughs complained about one feature: When they drive less than a mile, the device notifies them that they could have walked. Osborn said that’s not practical when she comes home alone from the library at night. Burroughs, who has used a wheelchair since a 1991 accident, just chuckles. “I use drive-ups a lot,” he said.

When the pilot was first conceived last year, it drew skepticism from privacy advocates, who worried about the state tracking people’s whereabouts. But because the program is currently voluntary, and no information about driving habits is sent to the state or law enforcement without a warrant, that criticism has been muted.

During debate on the program, the American Civil Liberties Union was assured that if it ever becomes mandatory, taxpayers could opt for an alternative to the GPS-based device. “We were able to get to a place where the ACLU did feel good about the program,” Becky Straus, legislative director for the ACLU of Oregon, said at the time.

The program was authorized for up to 5,000 participants, but since the July 1 start date, only 940 people have signed up. Some are concerned about privacy; others are reluctant because they simply do not want to get involved. Oregon is trying to get more people comfortable with the idea, in part through advertising.

California Driving

In 2014, the California Legislature directed state transportation officials to study the feasibility of replacing the state’s 42.4-cent gas tax with a road usage tax. The bill noted that if there is no change in the existing state gas tax, by 2030 as much as half of the gas tax revenue that could have been collected would be lost to fuel efficiency.

The study is underway and by the end of this year, signups will begin for an experimental program much like Oregon’s that is to start at the beginning of 2017. A report on the effort is due to the Legislature by the end of June 2018.

U.S. Rep. Mark DeSaulnier, a Democrat who was in the California Assembly when the bill passed, is the author of the legislation. He said he wrote it because of “a dire shortfall when it comes to investment in infrastructure.”

He said he had to overcome privacy concerns and “anti-tax people.” Supporters tried to address the privacy concerns by including an option allowing drivers to simply have their odometers read once a year and the mileage noted. But that would not differentiate out-of-state driving, as the GPS systems could. DeSaulnier said the federal government could learn from Oregon and California.

Congress has not addressed the federal gas tax of 18.4 cents a gallon, which has not been lifted in two decades and now generates 31 percent less than in 1998, according to ITEP. Without federal help, states have been forced to act.

Since 2013, 17 states have either increased old-fashioned gas taxes or set up some link to inflation. Georgia has done the most; it increased its gas tax by 6.7 cents this year and will raise it each July through 2018, based on growth in both fuel efficiency and inflation. After 2018, the increase will be based on fuel efficiency alone.

“I think the biggest problem here [in Washington, D.C.] is the majority party thinks they can invest in infrastructure without paying for it,” DeSaulnier said. “At some point the federal government has to do what the states are doing—find out how to fix the gas tax.”

Elaine S. Povich writes for Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

NEXT STORY: What Makes A Successful Public-Private Partnership?