State Lotteries Fight ‘Jackpot Fatigue,’ Casino Competition

States advertise, tweak lotteries to keep the money pouring in.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Elaine S. Povich.

With lottery proceeds flat or declining, and states reluctant to raise taxes to make up the difference, pressure is mounting to keep players playing and money rolling in.

In 22 of the 44 states with lotteries, revenue declined between 2014 and 2015, the most recent year for which comprehensive numbers are available. Twenty-one states also saw declines from 2013 to 2014. “Jackpot fatigue” — a drop off in lottery play until jackpots get unusually huge — is contributing to the decline, as well as fewer millennials playing, and competition from other forms of gambling. The explosive growth of casinos in particular has hurt some lotteries, as in West Virginia, where gamblers are drawn to the state’s own casinos, as well as new casinos in nearby Maryland and Pennsylvania.

In West Virginia, the lottery’s revenue decreased 2.6 percent in 2016. In Rhode Island, revenue was down 3.2 percent in 2016, and in Missouri, revenue was down 3.3 percent in 2015. Officials in many other states are facing similar numbers.

Roughly half of Americans bought a lottery ticket in the past year, according to a 2016 Gallup poll, down from 57 percent in 1999, when only 37 states had lotteries.

David Brunori, a professor of public policy at George Washington University who has written about state tax policy, blames jackpot fatigue and new gambling opportunities for the downturn, and said states are turning to more sophisticated advertising campaigns to keep interest up. If the ads weren’t running constantly, lottery revenue would be even lower, he said.

Brunori noted that revenue in the 44 states that have lotteries was about $21.4 billion in 2015. That’s not a huge amount compared to the $2.2 trillion states raised by all methods in 2015, but “it’s $21 billion in taxes they don’t have to impose on people, and that’s 99 percent” of the reason they do it, he said.

Some states funnel lottery money into the general budget, but most reserve it for a specific purpose, such as paying for schools. Colorado uses most of its lottery proceeds for environmental protection, while Massachusetts sends the money to local governments. In West Virginia, the lottery helps fund schools, senior services and programs to attract tourists. In crafting the current state budget, West Virginia lawmakers used some lottery dollars to fund Medicaid, rather than raise other taxes to cover that cost.

The reliance on lottery income means states have to continually fight to maintain bettors’ interest with new games and new ways to win. To boost interest and raise more money for the 44 states that participate, the multistate Mega Millions consortium recently announced it was upping ticket prices from $1 to $2 starting in October and restructuring prizes. Oklahoma, which saw sales diminish last year, increased prize amounts this year.

States also are increasing their lottery advertising budgets in an attempt to rake in more revenue. Massachusetts State Treasurer Deborah Goldberg, who oversees the lottery, early this year asked the Legislature to increase the lottery’s advertising budget from $8 million to $10 million to help it compete with casinos.

“It’s very critical as we move into this new era we focus on the fact that we will be competing with those that have had the capacity to brand themselves,” Goldberg said at a hearing on the budget, referring to a new casino project in the state. Goldberg is a proponent of online video sales, which the Legislature has not approved. An online lottery bill last year passed the Senate but not the House.

Many states contract with advertising agencies to create and promote the lottery, including coming up with new and exciting games periodically, said Carolyn Hapeman, spokeswoman for the New York State Gaming Commission.

West Virginia Lottery spokesman Randy Burnside said his state introduces 40 different instant games a year, and other states pursue a similar strategy. “You have to stay up with the industry practices with your gaming mix,” he said. “It’s a constant process of game development and introduction.”

Video ads for the West Virginia Lottery show people whitewater rafting and biking as a country band plays: “Home is where we love to play… Dreams can come true, it could happen to you, West Virginia Lottery.” The ad combines playing in rivers and woods with playing the games.

West Virginia state Sen. Charles Trump, a Republican, invoked the lottery during this year’s legislative session. He proposed a $52.5 million bond issue, backed by lottery money, to make previously authorized improvements to state parks. It failed, but he succeeded in calling attention to the lottery and what it pays for. “I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the state is dependent to a great degree for important programs on the lottery,” Trump said. “Yes, the state is looking all the time at ways to expand or protect it.”

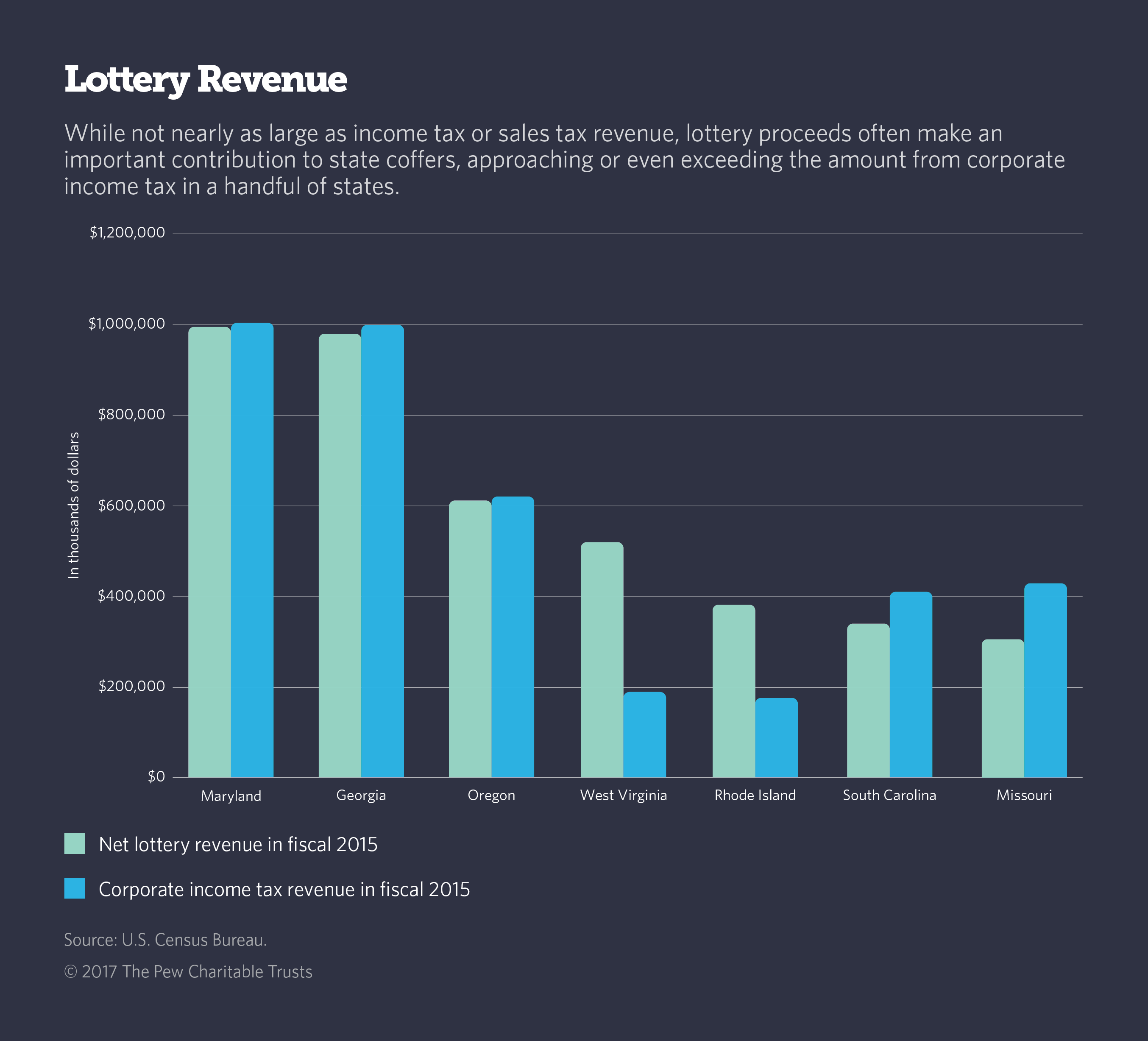

One way to gauge lotteries’ importance to state budgets is to compare their revenue to that of the corporate income tax, another small, but important, source of state dollars. Corporate income taxes amount to an average of 3 percent of state revenue while the lottery contributes 1 percent of state revenue. But in a handful of states, lottery revenue rivals or exceeds corporate income tax revenue.

Two states had significantly higher net lottery proceeds than corporate income tax collections: West Virginia, where the state garnered $520 million on $659 million in lottery sales in 2015 compared to $189 million in corporate income tax collections, and Rhode Island, where the state raised $383 million on $543 million in lottery ticket sales in 2015 compared to $176 million in corporate income tax collections.

Nationally, state lotteries generated $66.8 billion in gross revenue in fiscal 2015, which exceeds the $48.7 billion generated by corporate income taxes. However, $42.2 billion of the lottery income went into prizes and $3.2 billion went into administration (including advertising), leaving net lottery proceeds of $21.4 billion.

Jared Walczak, policy analyst at the Tax Foundation, a right-leaning think tank, pointed out that state lottery ticket sales are 37 percent higher than corporate income tax collections. “More money is spent on the lottery than on state corporate income taxes,” he said, though the state does not get to keep all that money due to prize payouts and expenses.